29th November 2024, A/Prof Chee L Khoo

We have written a bit on the paradigm change in our diagnosis and management of GDM over the last couple of years. We have looked at the TOBOGM study at length about early GDM (eGDM). This is GDM diagnosed before 24-week gestation. The TOBOGM study demonstrated that it is important to diagnosed early GDM as early treatment significantly improve neonatal and maternal outcomes. We know that women with GDM are at high risk developing T2D later in lifeWhat about women with eGDM? Are their risk of developing T2D any higher? And when does the dysglycaemia start?

The risk of developing T2D has been quoted to be 6-12 times that of women without GDM. Thus, it is recommended that women with GDM have an oGTT after the pregnancy. Unfortunately, women with GDM are often not followed up beyond the pregnancy. A recent sub-analysis of the TOBOGM study examined the post-partum glycaemic status of women who had eGDM.

You will recall that the Treatment of Booking Gestational Diabetes (TOBOGM) study was a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of immediate or deferred treatment of eGDM (<20 weeks’) among women at high-risk for GDM [12]. It was to examine whether there was benefit or harm in treating women diagnosed with eGDM. Follow up of these patients gave us a great opportunity to examine the glucose status of women diagnosed with eGDM. Note that In the TOBOGM trial, the exclusion of women with a fasting glucose ≥ 6.1 mmol/L or 2-hour glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L on the early oGTT. This may affect the incidence of postpartum dysglycaemia

Of 793 participants in the TOBOGM study, only 352 (44.4%) underwent a postpartum oGTT. There were no differences in baseline characteristics between participants who did, or did not, have a postpartum oGTT, with the exception that participants randomised to the immediate treatment arm of the TOBOGM RCT were more likely to receive treatment for GDM and have the follow-up oGTT. Those participants who had a postpartum oGTT were aged 32.4 ± 5.0 years, had a BMI of 31.9 ± 8.0 kg/m2, and 220 (63 %) were of non-European ethnicity

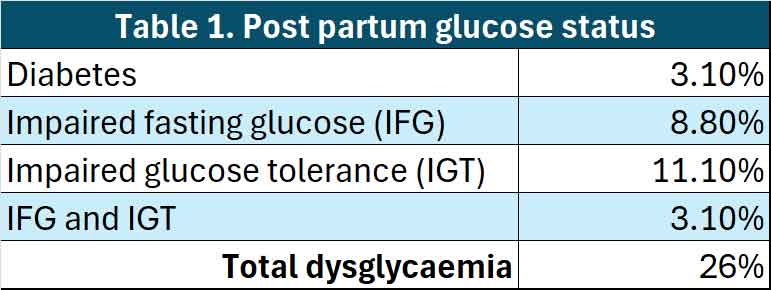

Ninety-two (26.1%) had postpartum dysglycaemia: 11 (3.1%) diabetes, 31 (8.8%) impaired fasting glucose (IFG), 39 (11.1%) impaired glucose tolerance (IGT), and 11 (3.1%) combined IFG/IGT. In other words, in women with eGDM, 26% continue to have glucoses abnormalities after the pregnancy. See Table 1.

Naturally, we would want to see whether there were any predictive factors for postpartum dysglycaemia.

Some of the women who were diagnosed with eGDM and randomised to no treatment were negative when tested again at 24-28 weeks oGTT while others tested positive at the 24-28 weeks. Of those who tested negative at 24-28 weeks, 11% had dysglycaemia postpartum while 27.4% of those who tested positive at 24-28 weeks had dysglycaemia.

Women with eGDM but in the higher band range, dysglycaemia was more likely (32%) while those in the lower band range, only 17.8% had dysglycaemia post partum.

In a multivariable analysis, there were patient characteristics that may predict post partum dysglycaemia:

- Past history of GDM

- 1-hour, 2-hour readings on initial oGTT

- Lower BMI

- Greater gestational weight gain

Unfortunately, they were only able to capture data from 44% of the women with eGDM. However, there were no differences in clinical characteristics between women who had, or did not have, a postpartum oGTT, which supports the validity of the findings of this study.

In summary, there is quite a high rate of post-partum dysglycaemia in women diagnosed with early GDM. There is recommendation that women with GDM (or eGDM) should have postpartum oGTT. Unfortunately, this is not always done for various reasons.

Reference: Cheung NW, Rhou YJJ, Immanuel J, Hague WM, Teede H, Nolan CJ, Peek MJ, Flack JR, McLean M, Wong VW, Hibbert EJ, Kautzky-Willer A, Harreiter J, Backman H, Gianatti E, Sweeting A, Mohan V, Simmons D. Postpartum dysglycaemia after early gestational diabetes: Follow-up of women in the TOBOGM randomised controlled trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2024 Nov 12;218:111929. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2024.111929.