14th March 2025, A/Prof Chee L Khoo

First it’s good then it’s not. We explored the role of colchicine in reducing cardiovascular disease (CVD) back in May 2024 when we looked at the LoDoCo2 trial. At the time, it was hailed as a significant development and colchicine made it into a couple of cardiology guidelines shortly after. Well, a couple of trials later, they are not so sure anymore. Does colchicine reduce CVD or not? I thought I had better check the whole story out as we all have more than a few patients who may benefit from colchicine if the experts decide it is beneficial.

We frequently hear about the “residual risk” in cardiovascular mortality and what they are referring to is the fact that despite managing all the known cardiovascular risks (e.g. hypertension, lipids especially LDL, body weight, glucose), patients with coronary artery disease continue to suffer from recurrent cardiovascular events. This is despite the use of high dose statins and anti-platelet therapy. We continue to discover new players in the residual risk space like lipoprotein (a) and hypertriglyceridaemia. While the residual risks continue to shrink, they remain significantly non-zero.

Some argue that none of the treatments actually target the underlying inflammatory pathway underpinning cardiovascular disease. Exposure to plaque contents incite aggressive inflammatory responses that may cause further plaque instability, further increase the risk of plaque enlargement and rupture and hence increase the risk of clinical events. Neutrophil infiltration of the plaque is a major instigator of the inflammatory process. Colchicine has anti-inflammatory properties, including an anti-tubulin effect that inhibits neutrophil function. Thus, it is plausible that colchicine can reduce cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD).

Stable coronary artery disease

Low-dose colchicine can reduce the risk of de novo vascular events caused by disruption of native atherosclerotic plaques in patients with stable coronary disease when it was first explored in the LoDoCo study as far back as 2013 here in Australia (1). 500 patients 35-85 years old with stable angiographically proven CAD were randomised to either 0.5mg of colchicine or control. The primary efficacy outcome was the composite of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), fatal or nonfatal out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, or non-cardioembolic ischemic stroke. After a median follow up of 36 months, colchicine reduced the primary outcome by 67%. The reduction in the primary outcome was largely driven by the reduction in the number of patients presenting with ACS. Uric acid levels or CRP were not mentioned in this study.

To further clarify the role of inflammation in CAD, Ridker et al randomised 10,601 patients who had a history of myocardial infarction and a CRP level ≥ 2mg/L to either placebo or 50mg, 150mg or 300mg of canakinumab in the CANTOS trial (2). Canakinumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody targeting interleukin-1β, an inflammatory cytokine that is central to the inflammatory response and that drives the interleukin-6 signaling pathway.

The primary efficacy end point was the first occurrence of nonfatal myocardial infarction, any nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death in a time-to-event analysis. After a mean follow up of 48 months, 50mg, 150mg and 300mg canakinumab reduced CRP by 26%, 37% and 41% respectively compared with placebo. All three doses of canakinumab reduced the primary end points (7, 15, 14% respectively) but only the reduction by the 150mg of canakinumab was statistically significant. However, there were more deaths from sepsis in the pooled canakinumab groups than placebo.

Acute coronary artery disease

Now, the LoCoDo and CANTOS trials were looking at patients with stable CAD. What about the potential instability of the coronary artery plaque in the shorter term? In the COLCOT trial, 4745 patients who had a recent (<30 days) AMI to either 500 mcg colchicine or placebo (3). The primary efficacy end point was a composite of death from cardiovascular causes, resuscitated cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, stroke, or urgent hospitalisation for angina leading to coronary revascularisation. There was a statistically significant 23% reduction in the primary end point in the colchicine intervention group over a median duration of receipt of the drug of 19.6 months compared with placebo. Most of the benefit came from reduction in strokes (hazard ratio 0.26) and coronary revascularisation (hazard ratio 0.5).

The mean CRP at baseline was 4.28 mg/L but was only measured in 207 patients. At the 6 months post AMI mark, CRP was reduced −70.0% in the colchicine group and −66.6% in the placebo group. The difference between the groups were not significant.

In the LoDoCo2 trial which we explored here in May 2024, 5478 patients 35-82 years old who has stable coronary artery disease were randomised to either 0.5mg colchicine or placebo and followed up over an average of 28.6 months (4). There was a 31% reduction in the primary outcomes (composite end-point event of cardiovascular death, spontaneous myocardial infarction, ischaemic stroke, or ischemia-driven coronary revascularisation) in the colchicine group compared with placebo. Most of the benefit came from reduction in myocardial infarction.

Well, since we previewed the LoDoCo2 study in May 2024, there were two further colchicine trials. In the CONVINCE trial, 3154 hospital-based patients with non-severe, non-cardioembolic ischaemic stroke or high-risk transient ischaemic attack were randomised to daily 0.5mg colchicine or usual care (5). The primary endpoint was a composite of first fatal or non-fatal recurrent ischaemic stroke, myocardial infarction, cardiac arrest, or hospitalisation for angina. There was a non-significant 16% reduction in primary end point between the colchicine and usual care groups. There was no significant reduction in CRP between the groups.

In the CHANCE-3 trial 8343 patients aged ≥ 40 years with a minor-to-moderate ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack and a high sensitivity C-reactive protein ≥2 mg/L were randomised to either daily 0.5mg colchicine or placebo (6). The primary efficacy outcome was any new stroke within 90 days after randomisation. There was only a nonsignificant 2% reduction in the primary outcomes.

Adverse reactions

There have been case reports have described serious colchicine toxicity in people taking a statin with colchicine due to competitive inhibition of CYP3A4 and P-gp. Myalgia and myotoxic effects occurred more commonly among colchicine-treated. Colchicine is metabolized by enteral and hepatic cytochrome P450 3A4. There may be drug-drug interactions when used with drugs that are metabolised by the same enzyme. Some of the drugs listed include amiodarone, dronedarone, quinidine, propafenone, diltiazem and verapamil. Colchicine should also be avoided in people with Child-Pugh class C liver disease.

The FDA approved indication allows for use with estimated glomerular filtration rate as low as 30 mL/min per 1.73 m2.

Thus, in patients with stable CAD, LoDoCo and CANTOS told us that colchicine is beneficial in reducing coronary events. In patients with shorter term CAD, LoDoCo2 and COLCOT told us that colchicine was also beneficial. CONVINCE told us that colchicine do not significantly reduced cerebral or coronary events in patients with strokes or TIA. CHANCE-3 similarly reported no significant improvement in strokes in patients who already had a stroke or TIA.

It seems that colchicine is beneficial in reducing coronary events in patients with CAD but not in reducing cerebrovascular events. The JUPITER trial demonstrated that primary prevention statin therapy among people with elevated CRP lowers the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (7). While colchicine has been shown to reduce CRP levels, none of the trials really require patients to have high CRP at enrolment and the analyses did not look at the contribution on CRP reduction in improving outcomes. The US Food and Drug Administration–approved indication also does not mention CRP testing either.

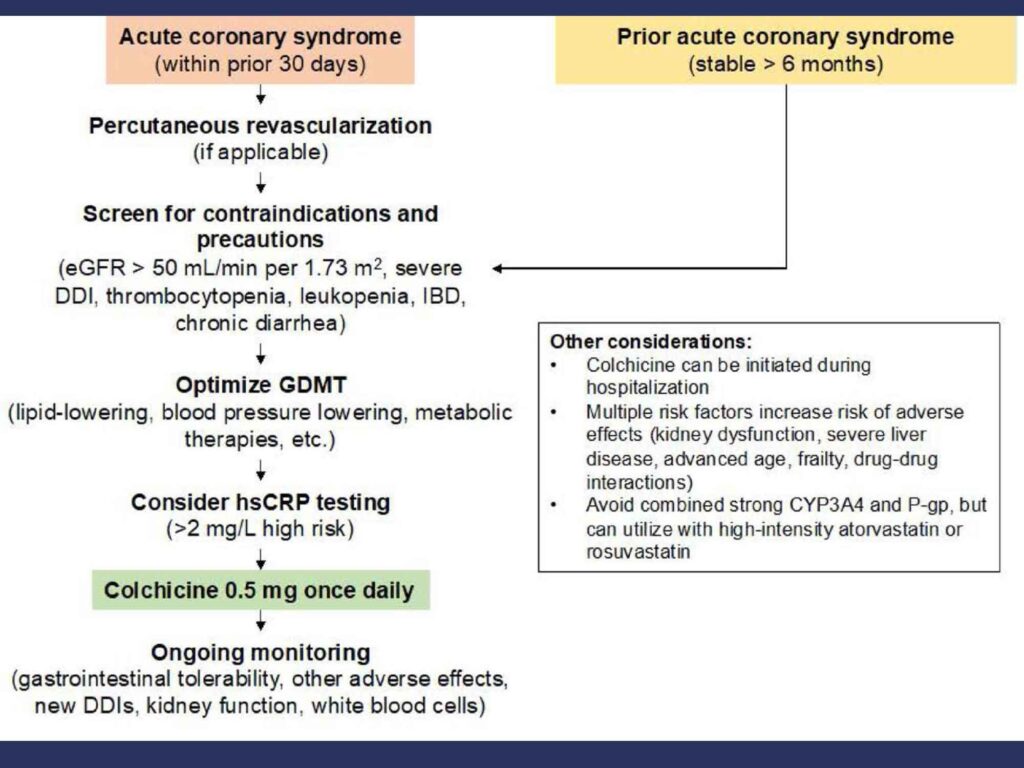

This is the proposed algorithm for considering the use of colchicine in secondary atherosclerosis prevention (8):

Somehow, CRP is used to decide whether colchicine is useful or not. Not sure that it is evidence based. In a patient who has high risk of recurrent cardiovascular events, perhaps, we should be thinking about adding colchicine irrespective of whether the CRP is elevated or not.

Hot off the press!!

In the CLEAR SYNERGY (OASIS 9) trial just published, Sanjit Jolly report that among patients who had myocardial infarction, treatment with colchicine, when started soon after myocardial infarction and continued for a median of 3 years, colchicine did not reduce the incidence of the composite primary outcome (death from cardiovascular causes, recurrent myocardial infarction, stroke, or unplanned ischemia-driven coronary revascularization).

References

- Nidorf SM, Eikelboom JW, Budgeon CA, Thompson PL. Low-dose colchicine for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jan 29;61(4):404-410. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.10.027. Epub 2012 Dec 19. PMID: 23265346.

- Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, et al. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1119-1131.

- Tardif J-C, Kouz S, Waters DD, et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose colchicine after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2019;381:2497-2505.

- Nidorf SM, Fiolet ATL, Mosterd A, et al. Colchicine in patients with chronic coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1838-1847.

- Kelly P, Lemmens R, Weimar C, et al. Long-term colchicine for the prevention of vascular recurrent events in non-cardioembolic stroke (CONVINCE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2024;404:125-133.

- Li J, Meng X, Shi F-D, et al. Colchicine in patients with acute ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack (CHANCE-3): multicentre, double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial. BMJ 2024;385:e079061-e079061.

- Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FAH, Genest J, Gotto AM, Kastelein JJP, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, MacFadyen JG, et al; JUPITER Study Group. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2195–2207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646

- Buckley LF, Libby P. Colchicine’s Role in Cardiovascular Disease Management. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2024 May;44(5):1031-1041. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.124.319851. Epub 2024 Mar 21. Erratum in: Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2024 Jul;44(7):e208.