21st November 2022, Dr Chee L Khoo

Have you noticed that we don’t use the term “CCF” anymore. The heart doesn’t have to be congested (as in fluid overloaded) to be in failure. We think about how the heart is not performing to its best to pump blood to all parts of the body that requires bloods. We call that heart failure because the heart has “failed” to pump blood adequately to tissues requiring blood. The diagnosis used to be, at least, in part, based primarily on symptoms. We explored the new universal definition of HF in July. The Australian HF consensus statement was released in August and we are now (almost) in line with international guidelines (1). The consensus statement is not just about the definition of HF but there are many details on management especially management by the GP. We ought to unpack the whole consensus statement as it relates critically to primary care.

Package 1. The universal definition of HF

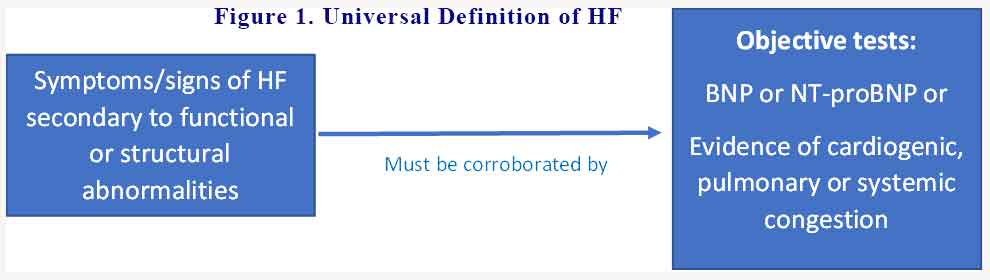

When you think about it, at present we diagnosed HF primary on the back of symptoms experienced by patients (remember the NYHA functional classification?) and perhaps, backed by some signs on physical examination. There really isn’t a requirement for an objective confirmation of “failure”. In any case, how do we define or confirm the failure? In the current guidelines, symptoms and signs of HF must be corroborated at least by either a blood test (brain natriuretic peptic (BNP) or NT-proBNP) or evidence of cardiogenic pulmonary or systemic congestion usually by echocardiographic or radionuclide studies. See Figure 1.

If we suspect our patient have HF, we need to refer them for either a blood test and/or further investigations usually with the cardiologist.

Package 2. The classification of HF

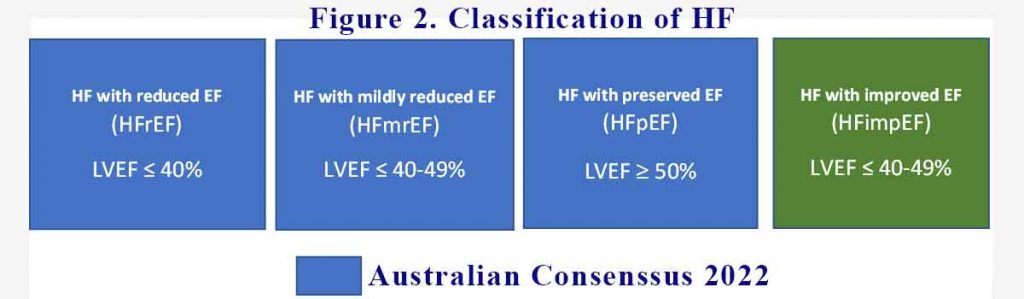

You would have heard about HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) depending on whether the EF is below 40% or above 50% respectively. Little do you know that the 40 or 50% numbers used were arbitrarily used in various clinical trials. It so happens that the efficacies of various pharmaceutical agents align with these numbers. In the current consensus statement, HF is classified as:

- HF with reduced EF (HFrEF) with EF ≤40%

- HF with mildly reduced EF (HFmrEF) with EF 41-49%

- HF with preserved EF (HFpEF) with EF ≥ 50%

- HF with improved EF (HFimpEF) for those whose EF is now between 40-50% with treatment

The last category is not in the Australian guidelines. It is an important category to remind us that even when the patient’s EF is now back towards normal, their mortality and morbidity risk remains significantly elevated. See Figure 2

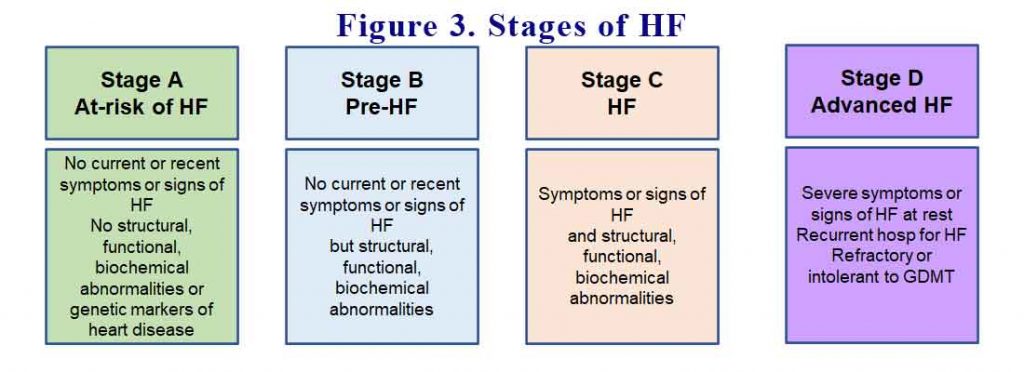

Package 3. The stages of HF

Like most things in medicine, prevention is often as important, if not more important than treatment. By listing the stages of HF, we are reminded in how to find those patients who have yet to have HF but either are at risk of HF or are in the pre-HF stage. Treatment should begin at those early stages. See Figure 3.

Package 4. The management of HF

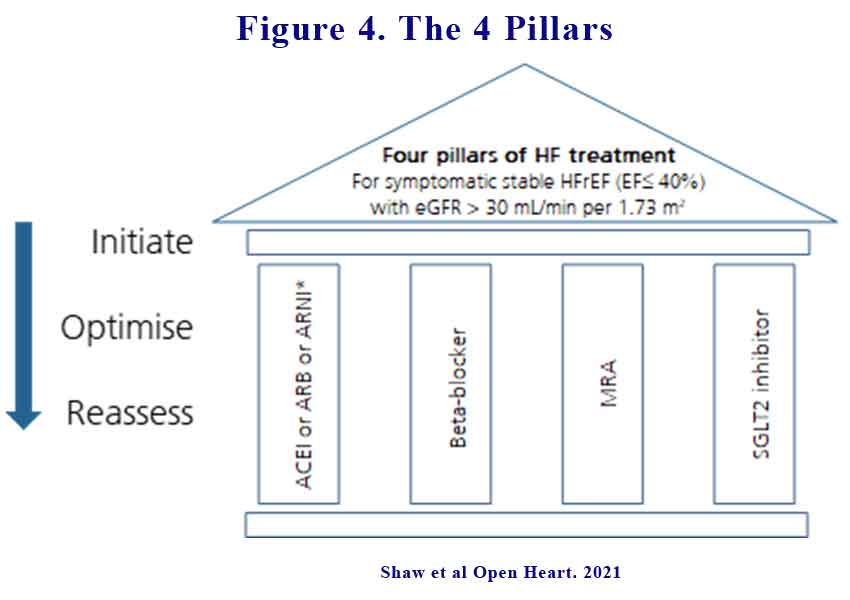

This is where there is a giant paradigm change in our management of HF. All available treatments to date for HF are guideline directed medical treatment for HFrEF. None of the HF treatments for HFpEF have been shown to improve mortality or morbidity thus far. Well, except for recent studies with the SGLT2 inhibitors which we reported here. There are a number of facets to the recommendations for management. It is now recommended that all patients with HFrEF MUST be on the 4 pillars of treatment:

- ACEi/ARB or ARNI

- Betablockers with proven HF efficacy

- Mineralocortical receptor antagonist (MRA)

- SGLT2 inhibitor.

See Figure 4 (6).

Not only should all patients with HFrEF be on all 4 classes of the drugs,

- All the agents must be commenced simultaneously and not sequentially if tolerated

- All agents must be titrated to their maximal doses as soon as possible (i.e. within weeks, perhaps a few months).

The maximal doses of the agents are:

- ARNI – 97mg

- MRA (spironolactone) 50mg per day

- Betablockers as per maximal dose on PBS

- SGLT2 inhibitors – Empagliflozin 10mg daily, Dapagliflozin 10mg daily

All the potential adverse effects are predictable and easily managed in general practice:

- Bradycardia (betablockers)

- Hypotension (betablockers, ACE/ARB/ARNI)

- Hyperkalaemia (MRA)

Package 5 – role of the GP

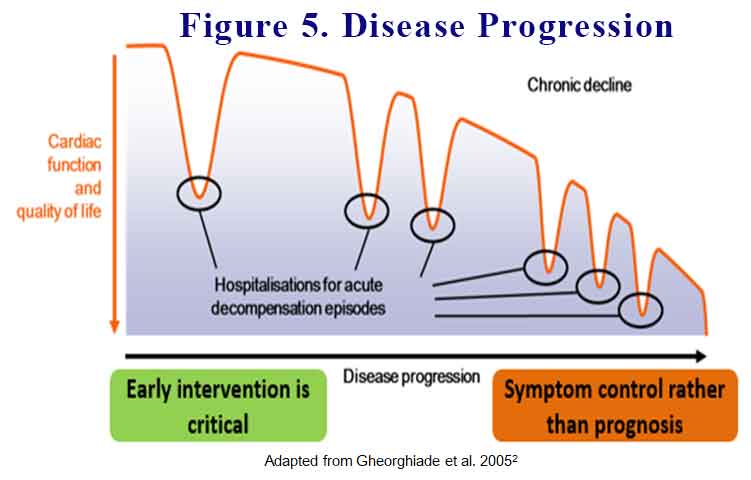

Unfortunately, most of our patients discharged from hospital are still not on all the 4 pillars as per guidelines. Further, it is another 6-8 weeks before they get to see the cardiologist. During that time, 1:3 patients would have been re-admitted into hospital because of their HF. Each time one of our patients is hospitalised for HF, their cardiac function is reduced. See Figure 5 (2).

As these guidelines are relatively new, not all our cardiologists (or their trainees) are up to date with the 4 pillars of management and the urgency they command. As GPs, we are expected to uptitrate the management without waiting for the cardiologist appointment.

8 people die every day because of HF (3). One in every 20-25 GP consults in people >45 years is a person with HF (4). 50-75% of patients diagnosed with HF die within 5 years of diagnosis (5). It is imperative that we ensure all our patients with HFrEF are on all these agents as soon as possible (simultaneously) and up-titrated maximally as soon as possible. These actions must happen during our watch in primary care.

References:

- Sindone A, De Pasquale, Amerena J et al. Consensus statement on the current pharmacological prevention and management of heart failure. Med. J. Aust. 2022

- Gheorghiade et al. Am J Cardiol 2005;96:11G–17G

- Heart Foundation. For professionals: Heart failure clinical guidelines. Available from: https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/conditions/heart-failure-clinical-guidelines Accessed January 2022

- Taylor CJ, Harrison C, et al. Heart failure and multimorbidity in Australian general practice. Journal of Comorbidity. 2017;7:44–9.

- Sahle BW, Owen AJ, Mutowo MP, Krum H, & Reid CM. (2016). Prevalence of heart failure in Australia: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders, 16, 32.

- Straw S, McGinlay M, Witte KK. Four pillars of heart failure: Contemporary pharmacological therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Open Heart. 2021;8(1)e001585