24th May 2025, A/Prof Chee L Khoo

One of the problems keeping up to date in primary care is not being aware of new guidelines that has been released. Well, the joint National Heart Foundation and Cardiac Society of ANZ released the new Australian clinical guideline for diagnosing and managing acute coronary syndromes (ACS) just a month ago (1). It is easy to think that there aren’t anything new that really applies to primary care patients. Most of these patients are managed either by the emergency department in the acute stages or by the cardiologists if coronary artery disease is confirmed. Apart from the major step forward in bringing down the target LDL-C to be in line with European, UK and US guidelines, there are really a lot of new information very relevant to primary care.

Terminology

There are a many new terms we will be using from here on. ACS encompass both acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and unstable angina (UA). ACS is now be classified as ST-segment elevation ACS (STEACS) and non-ST-segment elevation ACS (NSTEACS).

Myocardial infarction (MI) is the irreversible necrosis of heart muscle. Not all MIs are from occlusive events. Type 1 MI is characterised by atherosclerotic plaque rupture, ulceration, fissure or erosion with resulting intraluminal thrombus in one or more coronary arteries leading to decreased myocardial blood flow and/or distal embolisation and subsequent myocardial necrosis. Coronary artery disease (CAD) is not necessarily always obstructive (i.e. stenosis >70%) and may not be evident on angiograms.

Type 2 MI is myocardial necrosis associated with an imbalance between myocardial oxygen supply and demand, and may be associated with hypotension, hypertension, tachy/bradyarrhythmias, anaemia, hypoxaemia, coronary artery spasm, spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD), coronary embolism and coronary microvascular dysfunction.

ACS can also either be atherosclerotic or non-atherosclerotic. This guideline adopts the new term acute coronary occlusion myocardial infarction (ACOMI) in MIs from occlusive disease. Apart from atherosclerosis, the new terms reminds us not miss non-atherosclerotic cardiac disease especially in patients who don’t have the traditional CV risk factors. Thus, ACOMI include spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD), myocardial infarction in non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA), coronary embolism, coronary vasospasm or microvascular dysfunction.

Diagnosis

While chest pain is the most common symptom of ACS, it is not always present. Shortness of breath, fatigue, nausea, diaphoresis or vomiting are relatively common associative symptoms of ACS. Older adults and people with diabetes, may not describe any chest pain or discomfort.

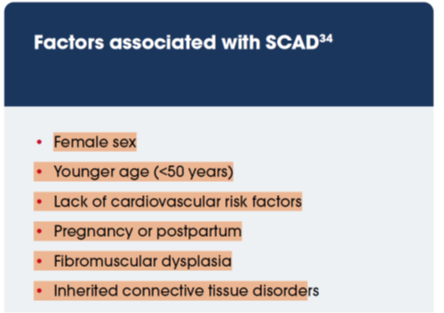

In women chest pains is still a common symptom but may include jaw, neck, shoulder or back pain, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, indigestion and shortness of breath (2-4). Women are more likely than men to be misdiagnosed with non-cardiac pain and are more likely to experience delays in receiving life-saving procedures in hospital and we should consider potential sex bias when interpreting symptoms (5,6). SCAD is a potential cause of ACS, particularly in young to middle-aged women. These women don’t usually have the traditional CV risk factors. See Figure 1.

ECG changes

Traditionally, ST segment elevation on ECG is the key criterion to determine where reperfusion is required but ST elevation can also be present in other cardiac and non-cardiac conditions. These include pericarditis, left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), left ventricular aneurysm, left bundle branch block (LBBB), right ventricular pacing, Takotsubo or other cardiomyopathies and Brugada patterns. Non-cardiac conditions include normal variant STE (early repolarisation), pulmonary embolism, hyperkalaemia, hypothermia and raised intracranial pressure.

Apart from ST elevations, other ECG abnormalities can raise suspicions of impending ACOMI:

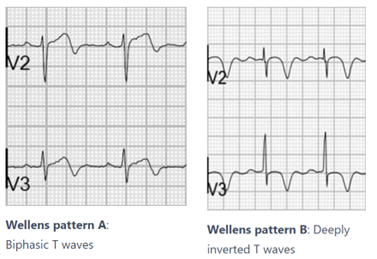

- Wellens T waves – biphasic or deeply inverted T waves in V2-3, plus a history of recent chest pain now resolved. It is highly specific for critical stenosis of the left anterior descending artery (LAD). See Figure 2.

- Diffuse ST-segment depression across multiple leads with STE in aVR

- Hyperacute T wave are symmetrical, broad-based T waves disproportionately large to the preceding QRS complex can be the first ECG finding of an evolving MI.

High-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn) is the preferred biomarker for diagnosing ACS due to its precision, early detection of myocardial injury and improved accuracy for MI. Hs-cTn results must be interpreted alongside the clinical context and ECG findings. Life-threatening conditions including aortic dissection and pulmonary embolism may result in elevated cTn values. Cardiac troponin elevation indicates myocardial injury but is not specific to the underlying pathophysiology. Reduced renal function can also lead to elevated cTn levels

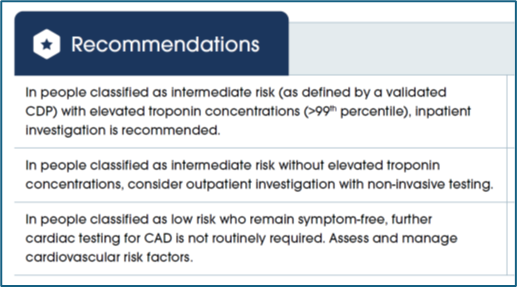

Further investigations in patients with suspected ACS

When patients with symptoms suggestive of ACS is discharged from hospital without a diagnosis of ACS, it is incumbent upon the GPs to further investigate the patient looking for evidence of CAD necessitating intensification of the patient’s management if appropriate. It is important to note that patients with high CV risk but do not have myocardial injury, the risk of of an MI, exceeds 50–70% (7) in the next 30 days. Urgent evaluation is required.

Which investigation?

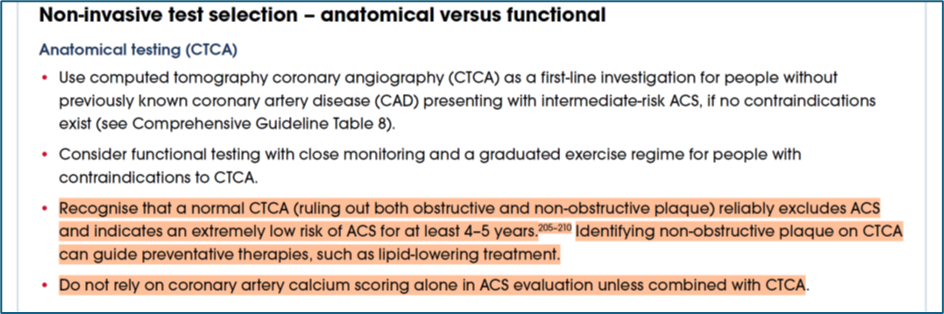

While we automatically think of a referral to cardiologist usually lead to a functional stress test, it is now recommended that the first-line investigation is a CTCA.

Management (including LDL-C targets)

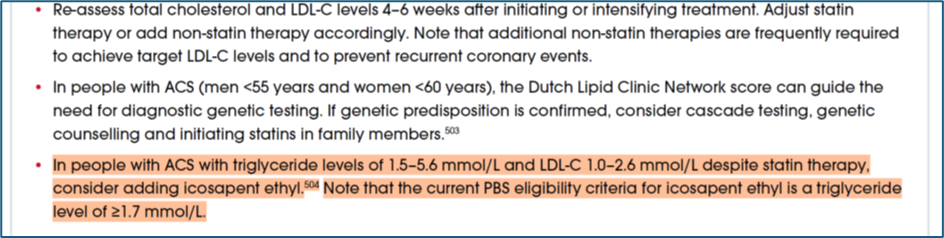

There are many recommendations for management in the guidelines for acute setting which is pretty much hospital based scenarios. The most relevant for primary care is the revision of the LDL-C targets. Australia has finally lined up with the rest of the OECD world and the new recommended treatment target for low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) is <1.4 mmol/L and a reduction of at least 50% from baseline. Further,

In summary, there are many causes of myocardial injury. Occlusive coronary artery disease is the most common but non-occlusive disease is increasing being recognise as a major cause. Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is a major cause of CAD but there are other non-ASCVD causes as well. Patients may have CAD without the traditional CV risk factors.

CTCA is now recommended as the first line investigation for people with suspected CAD. Unfortunately, Medicare still recognise functional stress test as first line. You may have to prompt your friendly cardiologist to consider the CTCA despite a normal stress test.

References:

- https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/for-professionals/acs-guideline Accessed 1st May 2025

- Lichtman JH, Leifheit EC, Safdar B, Bao H, Krumholz HM, Lorenze NP, et al. Sex differences in the presentation and perception of symptoms among young patients With myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2018;137:781–90.

- Khan NA, Daskalopoulou SS, Karp I, Eisenberg MJ, Pelletier R, Tsadok MA, et al. Sex differences in prodromal symptoms in acute coronary syndrome in patients aged 55 years or younger. Heart. 2017;103:863.

- Ferry AV, Anand A, Strachan FE, Mooney L, Stewart SD, Marshall L, et al. Presenting symptoms in men and women diagnosed with myocardial infarction using sex-specific criteria. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012307.

- Stehli J, Martin C, Brennan A, Dinh DT, Lefkovits J, Zaman S. Sex differences persist in time to presentation, revascularization, and mortality in myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012161.

- Chiaramonte GR, Friend R. Medical students’ and residents’ gender bias in the diagnosis, treatment, and interpretation of coronary heart disease symptoms. Healthy Psychol. 2006;25:255–66.

- Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, Barthelemy O, Bauersachs J, Bhatt DL, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:1289–367.