23rd August 2025, A/Prof Chee L Khoo

Not very often do you come across two significant studies on the same topic within weeks of each other. Over the last two months, two very interesting trials reported on the influence of exercise and fitness on risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) and the risk of recurrence of CRC. We know that being overweight or obese confer significantly higher risks of at least 13 different cancers (1,2). That is not surprising. We see that in practice. Weight loss interventions have been shown in many clinical trials to reduce all-cause mortality (3) although the data on specific reduction of cancer mortality is not as robust. Thus, the data from these two trials is valuable.

Christopher Booth et al presented an abstract from his randomised phase 3 trial on the impact of a structured exercise program on disease-free survival (DFS) in stage 3 or high-risk stage 2 colon cancer recently at the American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Scientific Meeting (4). 889 participants from 55 sites in 6 countries with resected stage 3 or high-risk stage 2 colon cancer who had received adjuvant chemotherapy were randomised to a structured exercise program (SEP) or health education materials (HEM). Now, the SEP was tough. SEP participantsworked with a physical activity (PA) consultant who delivered an exercise intervention using behaviour change methodology over 3 years. The goal was to increase recreational PA by at least 10 MET-hours/week from baseline during the first 6 months and sustain this for 3 years. The HEM participants, on the other hand, received education materials promoting PA and healthy nutrition in addition to standard surveillance. We know how adherent patients with exercise prescription is!

The primary endpoint of the intervention was disease-free survival (DFS) compared by a stratified log-rank test performed on an intention-to-treat basis. Secondary endpoints include overall survival (OS) and patient-reported outcomes (SF-36 physical function scale was primary PRO).

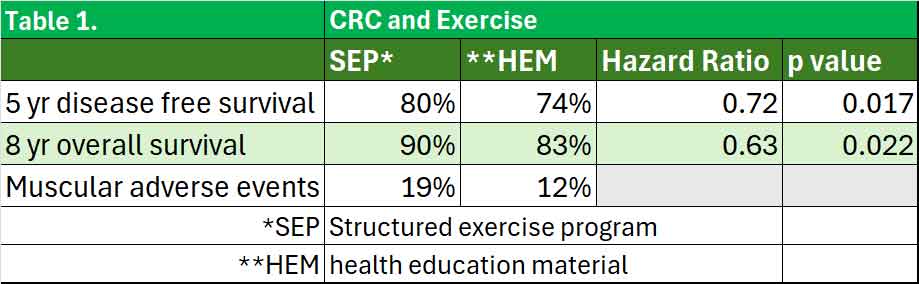

51% of the participants were female with the median age of 61 years. 90% participants had stage 3 disease. As expected, the SEP group had statistically significant improvements in recreational PA, predicted VO2max, and 6-minute walk distance, all maintained over the 3-year intervention period. With a median follow-up of 7.9 years, there were 224 DFS events (93 in SEP and 131 in HEM) and 107 deaths (41 in SEP and 66 in HEM) were observed. 5-year DFS was 80% in SEP and 74% in HEM (HR 0.72; 95% CI 0.55-0.94; p=0.017). 8-year OS was 90% in SEP and 83% in HEM (HR=0.63; 95% CI=0.43-0.94; p=0.022). SF-36 physical function was substantially improved with SEP at 6 months (mean change scores 7.42 vs 1.10, p,0.001) and was sustained to 24 months. See Table 1.

In the safety analysis, 19% (79/428) of patients on SEP reported any grade of musculoskeletal adverse event (MSK AE) over the course of the study, compared to 12% (50/433) on HEM. 10% (8/79) of MSK AE on SEP were considered to be related to participation in the PA program.

What about people who hasn’t had CRC? Will exercise and fitness help reduce the risk? Aamir Ali, Dominique E. Howard, Immanuel Babu Henry Samuel, et al explored the association between cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF), objectively measured by standardised exercise treadmill test (ETT) and colorectal cancer incidence (5). The Exercise Testing and Health Outcomes Study (ETHOS) involved 643,583 US veterans nationwide (41,968 women). Participants were excluded if they had cardiovascular disease or any cancers (including CRC).

Participants completed an ETT (Bruce) with no evidence of ischemia and were stratified into CRF categories (quintiles) based on peak metabolic equivalents (METs) achieved:

- least fit (n¼119,673; METs: 4.8 1.5)

- low fit (n¼157,059; METs: 7.3 1.4)

- moderate fit(n¼122,194; METs: 8.6 1.4)

- fit(n¼170,324; METs: 10.5 1.0), and

- high fit(n¼ 74,333; METs: 13.6 1.8)

During the median follow-up time of 10.0 years and 6,632,561 person-years of follow-up, 8190 patients had colorectal cancer, resulting in an incidence rate of 1.24 events per 1000 person-years. Individuals who had colorectal cancer were older (65.9 9.0 years vs 60.4 9.8 years; P<.001), exhibited higher systolic blood pressure (138.9 +/- 15.5 mm Hg vs 135.1 +/- 14.8 mm Hg; P<.001), and had lower CRF (7.4 +/- 2.6 vs 8.7 +/- 2.9 METs; P<.001) compared with those who did not have the disease.

Fit and highly fit individuals were significantly younger compared with the least-fit and moderately fit groups. In general, BMI, prevalence of comorbidities, and medication use were significantly lower or substantially more favourable for individuals with higher CRF categories. The prevalence of colorectal cancer was progressively lower with increased CRF for the entire cohort, regardless of sex or race.

The risk for development of colorectal cancer was higher in patients with hypertension (HR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.21 to 1.34; P<.001), patients with cardiovascular disease (HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.16 to 1.28; P<.001), and smokers (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.20; P<.001).

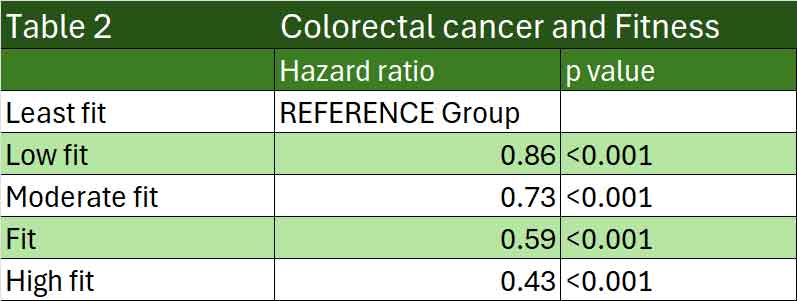

The risk of CRC was inversely proportional to fitness. Compared with the least fit group, increasing fitness led to increasing reductions in CRC incidence. See Table 2.

When they excluded participants who were diagnosed with CRC within two years of enrolment, the associations remained significant and consistent. They calculated that the risk of colorectal cancer was 9% lower for each 1-MET increase in CRF.

The CRF-colorectal cancer risk association followed a similar pattern for White individuals and African Americans. The trends were similar, although less clear, for Hispanics, Native Americans, and women because of a relatively small number of events in these subgroups.

The ETHOS study is one of the largest study examining the association between CRF and CRC incidence. Previous studies were inconsistent as there were issues relating to the accuracy of the fitness measures. Most relied on recall while this study used objective fitness measures.

Many of our patients who are at risk of CRC are also at risk of other cancers and cardiovascular events. In the pursuit of better outcomes, we must not only concentrate on weight loss. It’s never too late to reduce mortality and morbidity by recommending lifestyle changes especially cardiorespiratory fitness in our patients who are at risk of CRC or CRC recurrence. The role of the general practitioner is paramount in both groups of patients.

References:

- National Cancer Institute. Obesity and cancer. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/obesity/obesity-fact-sheet. Accessed August 2025.

- Lauby-Secretan B, et al. N Engl J Med 2016;375(8):794-798.

- Chenhan Ma, Alison Avenell, Mark Bolland et al. Effects of weight loss interventions for adults who are obese on mortality, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2017;359:j4849

- https://ascopubs.org/doi/pdf/10.1200/JCO.2025.43.17_suppl.LBA3510. Accessed 23/08/2025

- Ali A, Howard DE, Samuel IBH, Murphy R, Pittaras A, Campbell S, Becker OM, Mrkoci N, Myers J, Lavie C, Ladas A, Faselis C, Kokkinos P. Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Colorectal Cancer Incidence in US Veterans: A Cohort Study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2025 Jul 28:S0025-6196(25)00155-7.