13th March 2021, Dr Chee L Khoo

Medical treatment options for type 2 diabetes (T2D) have increased over the last decade and enhance the possibility of individualised treatment strategies where insulin is still one of them. In spite of the advancements in treatment options, less than one-third of the population with diabetes achieve their glycaemic target. What if I tell you that there is a new treatment option available that has been shown to significantly reduce HbA1c, hypoglycaemia, hospitalisation, complications and diabetic medications? A subset of patients are already utilising this treatment option and many others are coming on board. Are your patients utilising this option?

Of course, we are talking about continuous glucose monitoring (CGM). Now, HbA1c is usually our primary measure of glycaemic control and is traditionally recognised as the key surrogate marker for the development of long-term diabetes complication. Whenever we measure the efficacy of any anti-diabetic medication, we often use HbA1c as the primary outcome. However, this metric provides no information about the day-to-day acute glycaemic excursions (e.g., hypoglycaemia, hyperglycaemia) experienced by patients, nor does it identify the magnitude and frequency of intra- and inter-day glucose variation. It doesn’t reflect different daily and nocturnal patterns of glucose excursions and rates and extent of hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia.

Glycaemic variability is usually defined by the measurement of fluctuations of glucose or other related parameters of glucose homoeostasis over a given interval of time. Short-term glycaemic variability measures both within-day and between day glucose excursions. Short term glucose variability is increasingly being seen as an independent risk factor for diabetes complications. Short-term glycaemic variability was calculated from self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) measurements but this has been progressively replaced over the past few years by CGM.

The validity and accuracy of HbA1c is affected in chronic kidney disease, liver disease, iron deficiency with or without anaemia, recent blood loss or recent blood transfusion, haemoglobinopathies and pregnancy.

In persons with type 1 diabetes (T1D), CGM has shown to be the most important driver for improvement in glycaemic control, even more than insulin-pump therapy. Use of CGM has been shown to improve glycemia control, reduce hypoglycaemia, lower glycaemic variability and enhance quality of life for individuals withT1D and T2D. However, many primary care physicians may be unfamiliar with the how CGM data can interpreted and acted upon. As adoption of this technology continues to grow, primary care physicians will be challenged to integrate CGM into their clinical practices.

Large clinical trials and several real-world observational studies have demonstrated that use of CGM confers significant clinical benefits on patients with T1D and T2D treated with multidose insulin (1-6). However, we are now seeing a growing interest in expanding patient access to CGM across the broader type 2 diabetes regardless of their treatment regimen.

CGM can be important for patients who are at higher risk for hypoglycaemia, characterised by impaired hypoglycaemia aware-ness, frequent moderate/severe hypoglycaemia and or nocturnal hypoglycaemia. Severe hypoglycaemia is particularly problematic among older diabetes patients. These patients are at significantly higher due for due to their age, diabetes duration, glucose variability and higher prevalence of impaired hypoglycaemia aware-ness (7-12). Cognitive and physical impairments and other co-morbidities further increase the risk of severe hypoglycaemia among older patients (9).

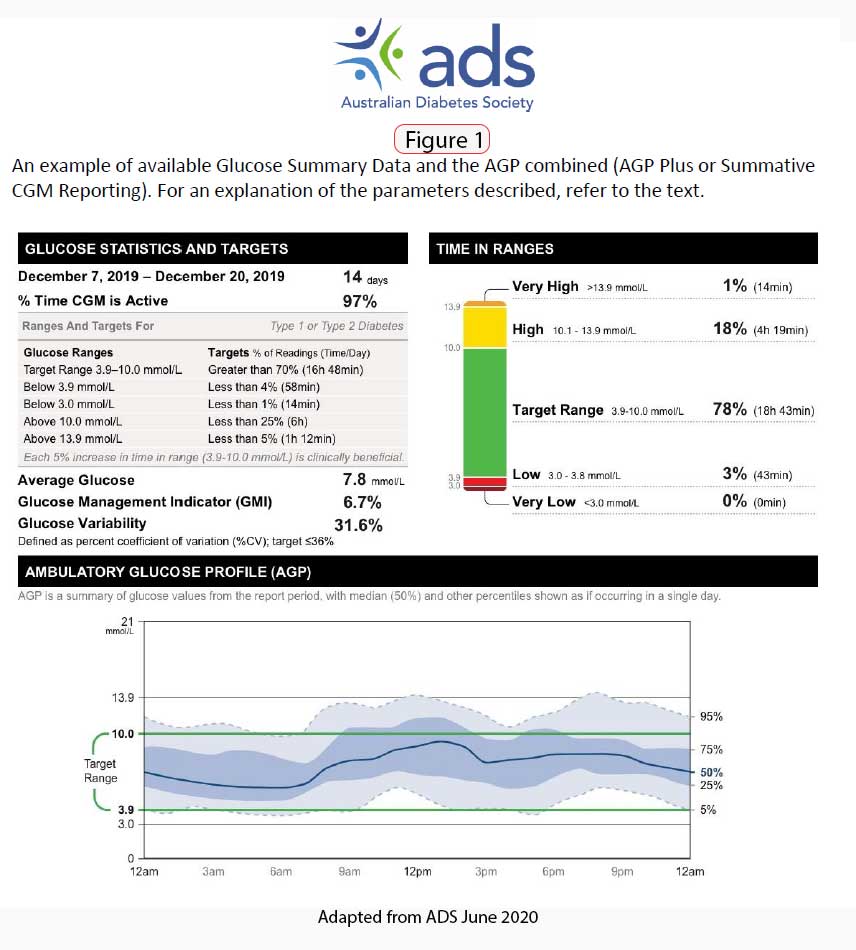

An expert panel met in 2013 to formulate recommendations for use of the Ambulatory Glucose Profile (AGP) as a template for presenting CGM data in a standardised report. Three of those metrics are considered to be most relevant:

- time in range (TIR) – aim for >70% of time spent at 3.9–10.0 mmol/L

- time below range (TBR) – aim for <4% of time at <3.9 mmol/L

- time above range (TAR) – aim for <1% at <3.0 mmol/L (13)

CGM makes a great patient education tool. As patients increasingly adopt CGM in their daily life, they gain valuable insights into their glucose response to food selection, meal timing and physical activity that facilitates more informed therapy adjustment decisions. This enhanced understanding can lead to greater proficiency in utilizing CGM data and increased confidence in patients’ ability to safely and effectively manage their diabetes.

The benefits of CGM use are greatly enhanced when patients are able to interpret and respond appropriately to the data in real time. This is available when patients use flash glucose monitoring (FGM) via Abbott’s Freestyle Libre.

The availability of CGM has also allow us to comfortably and confidently aim for lower and tighter glycaemic control in younger patients when we are comfortable that they are not at risk of hidde hypoglycaemia.

In Southwest Sydney, you will soon be seeing patients being discharged from hospital with a Freestyle Libre button attached and returning to see their GP with AGP reports to discuss their glycaemic control. Clinicians must understand how to analyse patient CGM data in order to evaluate patient status, assess the safety and effectiveness of the prescribed therapy and make adjustments as needed.

The ins and outs of the Freestyle Libre will be demonstrated at our Diabetes Quality Network’s inaugural CPD event at Campbelltown Catholic Club this Wednesday (March 17th, 6.30-9.00pm) or this Saturday (March 20th,12.30 – 3.00 pm) Mercure Hotel, Liverpool. Attending GPs have the option to experience first-hand by having the Freestyle Libre “button” attached that evening.

References:

- [4] R.W. Beck, T. Riddlesworth, K. Ruedy, et al., Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes using insulin injections: the DIAMOND randomized clinical trial, JAMA 317 (2017) 371–378.

- [5] R.W. Beck, T.D. Riddlesworth, K. Ruedy, et al., Continuous glucose monitor-ing versus usual care in patients with type 2 diabetes receiving multiple daily insulin injections: a randomized trial, Ann. Intern. Med. 167 (2017) 365–374.

- [6] J.ˇSoupal, L. Petruˇzelková, G. Grunberger, et al., Glycemic outcomes in adults with T1D are impacted more by continuous glucose monitoring than by insulin delivery method: 3 years of follow-up from the COMISAIR study, Diabetes Care43 (January (1)) (2020) 37–43.

- [7] R.W. Beck, T.D. Riddlesworth, K. Ruedy, et al., Effect of initiating use of an insulin pump in adults with type 1 diabetes using multiple daily insulin injections and continuous glucose monitoring (DIAMOND): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial, Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 5 (9) (2017) 700–708.

- S. Charleer, C. De Block, L. Van Huffel, et al., Quality of life and glucose controlafter 1 year of nationwide reimbursement of intermittently scanned contin-uous glucose monitoring in adults living with type 1 diabetes (FUTURE): aprospective observational real-world cohort study, Diabetes Care 43 (2) (2020)389–397.

- M. Fokkert, P. van Dijk, M. Edens, et al., Improved well-being and decreaseddisease burden after 1-year use of flash glucose monitoring (FLARE-NL4), BMJOpen Diabetes Res. Care 7 (1) (2019), e000809.

- R.S. Weinstock, S.N. DuBose, R.M. Bergenstal, et al., Risk factors associated withsevere hypoglycemia in older adults with type 1 diabetes, Diabetes Care 39 (4)(2016) 603–610.

- J.P. Bremer, K. Jauch-Chara, M. Hallschmid, S. Schmid, B. Schultes, Hypo-glycemia unawareness in older compared with middle-aged patients with type2 diabetes, Diabetes Care 32 (2009) 1513–1517.

- Z. Punthakee, M.E. Miller, L.J. Launer, et al., Poor cognitive function and risk ofsevere hypoglycemia in type 2 diabetes: post hoc epidemiologic analysis of theACCORD trial, Diabetes Care 35 (2012) 787–793.

- C.B. Giorda, A. Ozzello, S. Gentile, et al., Incidence and risk factors for severe andsymptomatic hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes. Results of the HYPOS-1 study,Acta Diabetol. 52 (5) (2015) 845–853.

- B. Cariou, P. Fontaine, E. Eschwege, et al., Frequency and predictors of confirmedhypoglycaemia in type 1 and insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus patientsin a real-life setting: results from the DIALOG study, Diabetes Metab. 41 (2)(2015) 116–125.

- E.R. Seaquist, J. Anderson, B. Childs, et al., Hypoglycemia and diabetes: a reportof a workgroup of the American Diabetes Association and the Endocrine Society,Diabetes Care 36 (2013) 1384–1395.

- Consensus Position Statement on: Utilising the Ambulatory Glucose Profile (AGP) combined with the Glucose Pattern Summary to Support Clinical Decision Making in Diabetes Care. https://diabetessociety.com.au/downloads/20200626%20ADS%20AGP%20Consensus%20Statement%2024062020%20-%20FINAL.pdf (Accessed 13th March 2021)

- Edelman SV, Cavaiola TS, Boeder S, Pettus J. Utilizing continuous glucose monitoring in primary care practice: What the numbers mean. Prim Care Diabetes. 2021 Apr;15(2):199-207. doi: 10.1016/j.pcd.2020.10.013. Epub 2020 Nov 28. PMID: 33257275.