12th June 2022, Dr Chee L Khoo

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common liver condition in the western world. A significant proportion of these patients developed inflammation and progressed to non-alcoholic steato-hepatitis (NASH). Further and persistent inflammation can lead to cirrhosis and ultimately, to liver failure or liver cancer. Management till recently is primarily targeted towards lifestyle measures to reduce liver fat. Unlike most other major medical conditions, early diagnosis have not been beneficial as there are currently no effective and approved treatments to reduce the fibrosis or progression. There are a large number of agents targeting different pathophysiological pathways in the pipeline with a number in Phase 3 clinical trials.

The primary pathophysiology of NAFLD is the accumulation of fat in the liver, largely in the form of triglycerides. However, the mechanisms by which triglycerides accumulate and the reasons that accumulation can lead to liver dysfunction are complex and incompletely understood.

There are four different clinical phases described for NAFLD:

- Phase 1 – characterised by simple steatosis and is considered harmless.

- Phase 2 – developing inflammation and ballooning (NASH).

- Phase 3 – defined by the presence of NASH with persistent inflammation resulting in liver fibrosis

- Phase 4 – Cirrhosis leading to liver failure, hepatic cancer

During the early stages of this disease, patients often show few or non-specific symptoms, such as tiredness, fatigue or abdominal pain, and therefore NASH is often not diagnosed until later stages of disease progression, using invasive techniques such as liver biopsy.

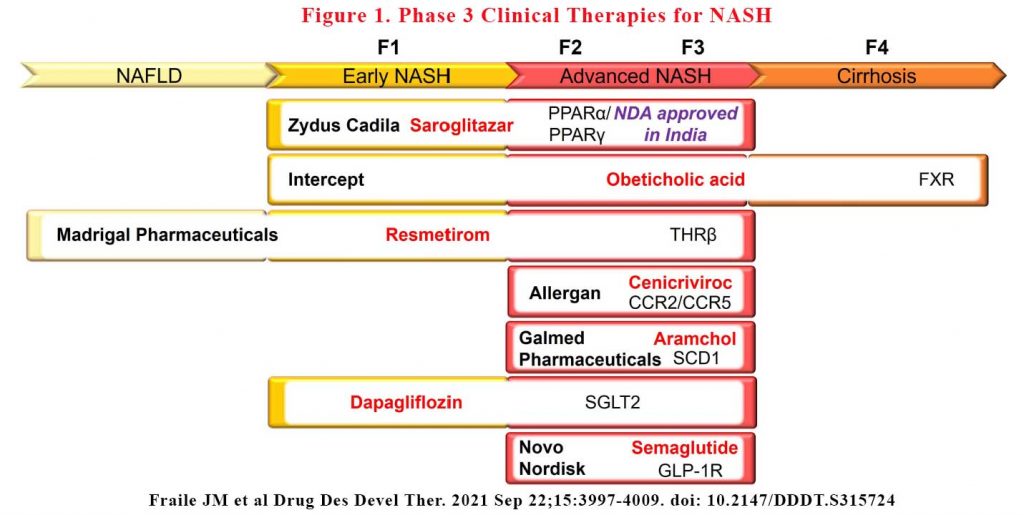

There are a large number of drugs in the pipeline targeting mostly early and advanced NASH stages. There are only a handful of agents are in the late-stage clinical development. Some are totally new drug classes while others are existing drugs repurposed for NAFLD. Many candidates have failed to meet predefined efficacy endpoints while others have failed safety endpoints.

Saroglitazar is a first-in-class therapy already approved in India for the treatment of type 2 diabetes (T2D) and dyslipidaemia that acts as a dual peroxisome proliferator-activator receptor (PPAR) alpha and gamma agonist, lowering high blood triglycerides and blood sugar. The PPAR family is composed of three members, PPARα, PPARγ and PPARδ, which are ubiquitously expressed in different organs and play an essential role in lipid and glucose metabolism, and inflammation (1). It achieved positive results in Phase 3 trials in India and met its primary endpoint of reduced ALT in Phase 2 trials in US in October 2020.

Obeticholic acid is a semisynthetic analogue of the bile acid, chenodeoxycholic acid, and acts as a Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonist. FXR is a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily that regulates a variety of genes involved in bile acid synthesis and transport, and in glucose and lipid metabolism (2). Already approved for the treatment of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), Unfortunately, FDA rejected the company’s NDA for NASH treatment in June 2020. There were issues with some liver toxicity signals and adverse effects on lipids.

Resmetirom is a first-in-class oral thyroid hormone receptor-beta (THRβ) agonist. THRβ is the main receptor for thyroid hormones in the liver and plays an essential role in lipid metabolism (3). The Phase 3, 52-week study demonstrated that resmetirom was safe and well-tolerated and helped patients with presumed non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) achieve significant, clinically relevant reductions in liver fat measured by liver MRI. It also significantly reduced atherogenic lipids, including LDL-C, apolipoprotein B and triglycerides.

Cenicriviroc (CVC), is a novel, orally administered, potent, small molecule agonist that acts to block chemokine 2 and 5 receptors (CCR2/CCR5), both with well- known roles in liver inflammation and fibrosis (4). It did not meet its primary outcome of NAFLD activity score (NAS), which is a composite of steatosis, inflammation and hepatocyte ballooning and represents a measure of disease activity although it did improve liver fibrosis. Phase 3 trials is continuing.

Aramchol is a first-in-class, once-daily, oral stearoyl- coenzyme A desaturase-1 (SCD1) modulator. SCD1 is considered a mediator of liver steatosis and fibrosis because of its role in fatty acid biosynthesis (5,6). In Phase 2b clinical trials, Aramchol treatment in 247 NASH patients who were all clinically overweight or obese and had prediabetes or T2D demonstrated liver fat reduction, biochemical improvement and both NASH and fibrosis resolution, with favourable safety and tolerability profiles. Phase 3/4 will report sometime this year.

Lanifibranor is an oral small molecule that activates all three PPAR isoforms (PPARα, PPARδ and PPARγ), inducing anti-fibrotic, anti-inflammatory and other beneficial metabolic changes in the body, and delivers these outcomes by decreasing triglyceride levels and increasing high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and insulin sensitisation. It is the only pan-PPAR agonist in clinical development for NASH. A 24-week Phase 2b trial demonstrated that the higher dose used in this study reduced by at least two points the steatosis activity fibrosis (SAF) score (SAF is a measure that combines the degree of hepatocellular inflammation and cellular ballooning) with no worsening of fibrosis (primary endpoint). Phase 3 NATiVE3 pivotal clinical trial with Lanifibranor is now recruiting its first patients.

Campbelltown Hospital is part of the multinational NATiV3 trial and is now recruiting. Click here for more information on recruitment.

Existing anti-diabetic drugs such as dapagliflozin, liraglutide, dulaglutide and semaglutide are now under late-stage consideration for NASH. In addition, several new diabetic agents are in clinical trials for NASH treatment, including sodium-glucose co- transporter-1/2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonists. Further, there are a number of clinical trials utilising combination of agents (e.g. semaglutide and FXR agonist). Several monoclonal antibodies are also on trial.

See Figure 1

NASH is associated with cardiometabolic risks and in fact, cardiovascular disease is the major cause of death in these patients. The increased cardiometabolic risk exist in all stages of NAFLD. A group of experts have proposed the term, Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD) as a more appropriate term to reflect the heterogeneity of this disease (7).

NAFLD is very, very common in general practice and have serious complications. Aggressive lifestyle measures is vital in primary care. It’s not “just fatty liver”. LFTs are not always abnormal in the early stages of the disease. There are many drug classes coming to market very soon.

References:

- Sanderson L. PPARs: Important Regulators in Metabolism and Inflammation. Vol. 8. Dordrecht: Springer; 2010

- Lefebvre P, Cariou B, Lien F, Kuipers F, Staels B. Role of bile acids and bile acid receptors in metabolic regulation. Physiol Rev. 2009;89 (1):147–191. doi:10.1152/physrev.00010.200814.

- Sinha RA, Bruinstroop E, Singh BK, Yen PM. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hypercholesterolemia: roles of thyroid hormones, metabolites, and agonists. Thyroid. 2019;29(9):1173–1191. doi:10.1089/thy.2018.066417.

- Marra F, Tacke F. Roles for chemokines in liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(3):577–594e571. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.06.043

- Miyazaki M, Flowers MT, Sampath H, et al. Hepatic stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 deficiency protects mice from carbohydrate-induced adiposity and hepatic steatosis. Cell Metab. 2007;6(6):484–496. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.014

- Iruarrizaga-Lejarreta M, Varela-Rey M, Fernandez-Ramos D, et al. Role of aramchol in steatohepatitis and fibrosis in mice. Hepatol Commun. 2017;1(9):911–927. doi:10.1002/hep4.1107

- 4. Eslam M, Sanyal AJ, George J, International Consensus P. MAFLD: a consensus-driven proposed nomenclature for metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(7):1999–2014e1991. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.11.312

- Fraile JM, Palliyil S, Barelle C, Porter AJ, Kovaleva M. Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) – A Review of a Crowded Clinical Landscape, Driven by a Complex Disease. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2021 Sep 22;15:3997-4009. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S315724