10th February 2025, A/Prof Chee L Khoo

We perform cardiovascular (CV) risk assessments in our consulting rooms everyday. We assess lipid profiles, smoking history, family history and activity levels in our patients routinely and try to quantify the likelihood they may have a cardiovascular event. Over the years at GPVoice we have tried to expand beyond the traditional risk factors as more data come to hand. We looked at lipoprotein (a), hypertriglyceridaemia and metabolic dysfunction associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) as CV risk enhancers. The presence of risk enhancers mandate that we intensify our risk mitigation strategies and relook at biochemical targets especially LDL-Cholesterol. What about pregnancy related disorders? Are these CV risk enhancers as well?

Heart disease is still the leading cause of death with the increase in obesity and decrease in physical activity across society. In the US, CV disease (CVD), claims more lives than all forms of cancers and accidental deaths (the number two and three causes of death) combined (1). Women are not immune from these sad statistics even though theoretically, their oestrogens somewhat “protect” them for some years till menopause hit.

We have been pre-occupied with adverse offspring outcomes in women with pregnancy related disorders as pregnancy-related maternal morbidity in the world has increased nearly 200% between 1993 and 2014 in the USA (2). These morbidities include hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDPs), such as pre-eclampsia, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), preterm delivery and small-for-gestational-age infants. These adverse pregnancy outcomes (APOs) are common and occur in 17–20% of all pregnancies in the USA (3).

The 2018 American College of Cardiology/AHA guideline on the management of cholesterol introduced the concept of risk-enhancing factors, conditions that, when present, suggest the need for initiation or intensification of statin therapy among individuals at borderline or intermediate 10-year ASCVD risk (5). For example, women with gestational diabetes (GDM) are 4 times more likely to develop subsequent diabetes mellitus and 59% more likely to suffer a myocardial infarction (5). Further, a history of GDM was associated with a 68% increase in ASCVD in a meta-analysis of 8 studies (5).

It’s not just GDM but gestational hypertension is increases the risk of future CAD (6). The risks are even higher in moderate pre-eclampsia (2.24X) and severe pre-eclampsia (2.74X) (5). Similarly, women who delivered a small for gestational age baby have a 1.8X higher risk of CAD (7). Preterm pregnancies increase the future risk of CAD by 1.6X (5).

These risk enhancers are further magnified in ethnic minority groups and those of the lower socioeconomic background. This is particular relevant in southwest Sydney.

A retrospective analysis conducted at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center showed that 39% of the women with premature myocardial infarctions experienced a prior APO (8). In the Cardiovascular Risk Profile: Imaging and Gender-Specific Disorders Study, 31% of women with previous pre-eclampsia aged 45–55 years had a CACS of >0 in comparison with 18% of women with a previous normotensive pregnancy who were matched for gender, age and ethnicity. Moreover, 47% of women with previous pre-eclampsia had coronary atherosclerotic plaques on coronary CT angiography (CCTA) and 4.3% had significant stenosis (9). Most recently, a large study of CCTA in Swedish women aged 50–65 years showed the prevalence of coronary atherosclerosis in women with a history of any APO was 32.1% significantly higher (prevalence difference, 3.8% prevalence ratio, 1.14 compared with reference women from Sweden (10).

Yes, APOs affect the future metabolic and cardiovascular risks of the offsprings but there is mounting evidence for many decades now that a history of APOs predicts later-life risk of CVD including coronary artery disease (CAD) and heart failure (HF) (5, 11). It is particularly important to optimise the management of these CV risk factors during (and before) pregnancy. It is also important to protect the future health of these women in primary care as we will be looking after them for decades to come and this open up opportunities.

We should be looking at these APOs as early warning cardiac events just TIAs are to future stroke or CAD events. It’s like a “stress test” that we are so familiar with. We don’t know whether the APOs are harbingers of future events that is to come in certain women who are at risk anyway or whether APOs already present during (or before) pregnancy mediate accelerated cardiovascular ageing.

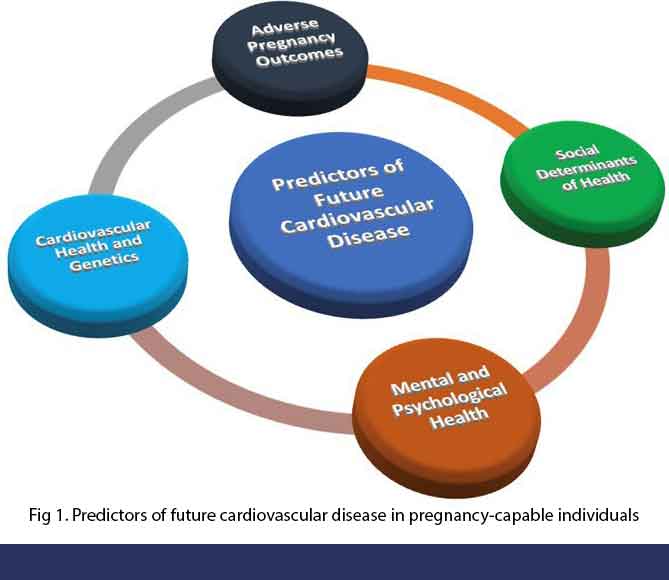

The concept of APOs as an early warning sign means when we take a CV history, we need to interrogate the presence of APOs. It is important to mark women returning for their 6-week post-partum check for aggressive risk factor management for life. We need to manage all the CV risk factors. The same concept should also remind us to screen all fertile young women for CV risk factors that should be managed prior to conception. See Figure 1.

It may require referrals to appropriate allied health professionals to improve lifestyle measures including healthy diet and physical activity. Or a referral to the Get Healthy Service. The Get Healthy Service (GHS) is a NSW Health funded free phone and online health coaching service. It is designed to assist our patients to make lifestyle changes (diet and physical activity) to improve health. It is open to all NSW residents over 16 years old. It has been around for some years now although it has largely operated without GPs being aware of its existence. The service is now provided by Diabetes Australia. You can refer patients directly from your medical software (Best Practice or Medical Director). The instructions are here.

References:

- Martin, Seth S. Aday, Aaron W. Allen, Norrina B., et al. on behalf of the American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Committee 2025 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data From the American Heart Association. Circulation 27 January 2025. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001303

- Levels of maternal care. 2015. Available: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/obstetric-care-consensus/articles/2019/08/levels-of-maternal-care [Accessed 10 Sep 2023].

- Lane-Cordova AD, Khan SS, Grobman WA, et al. Long-term cardiovascular risks associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:2106–16.

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, et al. AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/Apha/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 2019;139:e1082–143.

- Parikh NI, Gonzalez JM, Anderson CAM, et al. Adverse pregnancy outcomes and cardiovascular disease risk: unique opportunities for cardiovascular disease prevention in women: a scientific statement from the American heart association. Circulation 2021;143:e902–16.

- Lo CCW, Lo ACQ, Leow SH, et al. Future cardiovascular disease risk for women with gestational hypertension: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e013991.

- Bukowski R, Davis KE, Wilson PWF. Delivery of a small for gestational age infant and greater maternal risk of ischemic heart disease. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e33047.

- Countouris ME, Koczo A, Reynolds HR, et al. Characteristics of premature myocardial infarction among women with prior adverse pregnancy outcomes. JACC Adv 2023;2:100411.

- Zoet GA, Benschop L, Boersma E, et al. Prevalence of subclinical coronary artery disease assessed by coronary computed tomography angiography in 45- to 55-year-old women with a history of preeclampsia. Circulation 2018;137:877–9.

- Sederholm Lawesson S, Swahn E, Pihlsgård M, et al. Association between history of adverse pregnancy outcomes and coronary artery disease assessed by coronary computed tomography angiography. JAMA 2023;329:393–404.

- Honigberg MC, Zekavat SM, Aragam K, et al. Long-term cardiovascular risk in women with hypertension during pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:2743–54.