30th June 2025, A/Prof Chee L Khoo

You would have no doubt noticed headlines everywhere about the new criteria for GDM diagnosis that was just released a few days ago. Why is there such a buzz? Why is everyone seemingly that excited? We have covered many of the issues covered by ADIPS over the years leading up to this new guideline. It’s finally here and it’s important to have a helicopter view of the whole rationale and process leading up to the new announcement. It’s not just a new set of numbers which is not that new anyway.

It has been known for many years that hyperglycaemia during pregnancy leads to poor outcomes in both mother and offsprings but it wasn’t till Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes (HAPO) reported in 1991 that the numbers could be quantified(1). The only problem is that initial analysis from HAPO suggests that any degree of hyperglycaemia is harmful. This made it hard to draw a definitive safe line. A decision was made to draw a line somewhere according to the odds ratio (OR) of causing harm. Some jurisdictions used an OR of 1.75 where the glucose cut offs were 5.1, 10, 8.5 mmol/L for the 0,1,2-hour 75g pregnancy oral glucose tolerance test (POGTT) respectively while others used the OR of 2.0 where the glucose cut offs were 5.3, 10.6 and 9.0 mmol/L. The ADIPS 2014 GDM criteria was based on the OR 1.75 cut offs (2).

Subsequent re-analyses discovered that women with fasting of <4.7 mmol/L had similar perinatal outcomes to women without GDM irrespective of post load readings (3).

There was another curly problem. The recommendations and cut offs from the HAPO study was based on the 24-28 week POGTT. Since then, there has been data to demonstrate that in a significant proportion of women with GDM, their glucose readings were already high early during the pregnancy before the 24-28-week test. Treating these women after the 24-28 week diagnosis might be too late to prevent perinatal complications. The concept of diagnosing GDM early made sense in these women. We needed data to demonstrate that treating women with early GDM diagnosed wasn’t only beneficial but not harmful.

Of course, at GPVoice we have been keeping you up to date of proceedings. The Australian-led TOBOGM randomised controlled trial (RCT) commissioned by Professor David Simmons published in 2023 showed that immediate treatment of GDM diagnosed before 20 weeks based on the WHO 2013 criteria) modestly reduced the risk of the perinatal composite outcome (4). Treatment did not adversely affect neonatal lean body mass. Pre-specified subgroup analyses suggested that the benefit was seen in women with high glycaemic band based on HAPO OR 2.0 OGTT diagnostic thresholds, but not in women diagnosed with the currently recommended low glycaemic band thresholds (HAPO OR 1.75). Early treatment for gestational diabetes mellitus was also found to be cost-effective among high-risk women in the higher glycaemic band when diagnosed before 14 weeks’ gestation (5).

The New Zealand Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Study of Detection Thresholds (GEMS) randomised controlled trial confirmed the benefits of treating women with the higher thresholds (OR 2.0) (6). Treating of women using the lower threshold in the GEMS trial was associated with greater health service use and an increased risk of small for gestational age offspring as well as lower lean mass and increased risk of early term birth (6,7)

The results from TOBOGM really set the world on fire. All jurisdictions across the globe had to revised their GDM cut offs as well as their testing regimen. Here in Australia, the ADIPS convened the IADPSG Summit on gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosis in early pregnancy in November 2022 and a workshop for ADIPS members in August 2023 regarding screening and diagnosing early gestational diabetes mellitus. They consulted widely across multiple disciplines including general practice. I was priviledged to be part of the workshop. The final consensus recommendations just published this week comes after an incredibly arduous and lengthy process overseen by the elected multidisciplinary ADIPS Board.

Criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus (8)

The diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus at any gestation should be based on any one of the following values:

- FPG ≥ 5.3–6.9 mmol/L;

- 1hPG ≥ 10.6 mmol/L; and/or

- 2hPG ≥ 9.0–11.0 mmol/L

during a 75 g two-hour POGTT. You can recognise the values as the HAPO OR 2.0.

Early testing for GDM

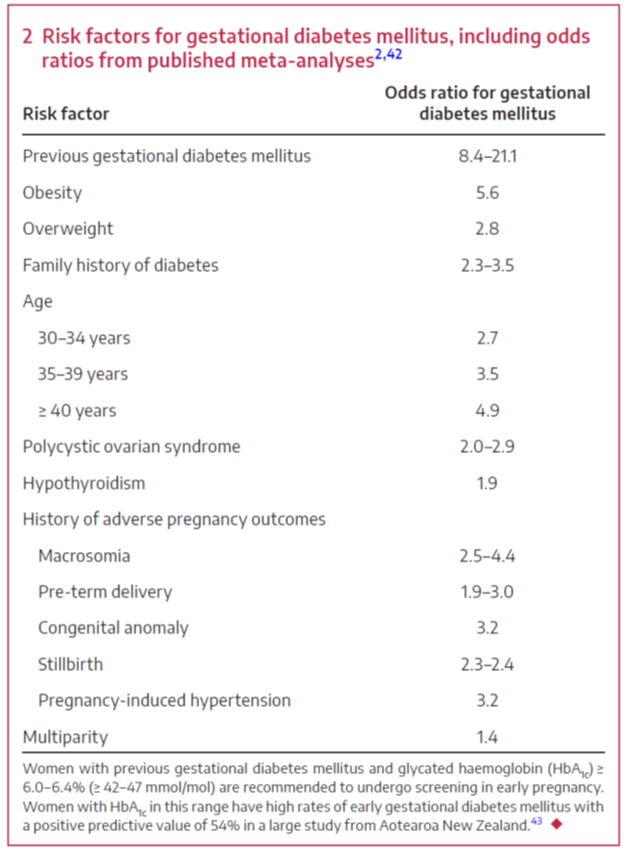

Women with risk factors for hyperglycaemia in pregnancy (Figure 1) and women whose early pregnancy HbA1c is in the prediabetes range (≥ 6.0-6.4%) should be advised to undergo a 75 g two-hour POGTT before 20 weeks’ gestation, ideally between 10 and 14 weeks’ gestation but considering factors such as nausea. POGTT should not be performed before ten weeks’ gestation due to poor tolerance and limited evidence of benefit. Women with risk factors should have HbA1c measured at the first antenatal visit (generally in the primary care setting). The intent is to identify women with overt diabetes in pregnancy (DIP).

Women who have not had GDM diagnosed in early testing, should be advised to undergo the 24-28 week gestation POGTT. The working group agonised over the fact some women will have to undergo the POGTT twice in the pregnancy.

When POGTT is not undertaken

Some women are unable to tolerate an POGTT or choose not to. It is suggested that these women undergo fasting plasma glucose (FPG) measurement. However, these women should be informed that gestational diabetes mellitus cannot be fully excluded without a POGTT.

The evidence for the threshold for self-blood glucose monitoring or continuous glucose monitoring is unavailable. HbA1c at later pregnancy is not recommended for gestational diabetes mellitus screening due to poor sensitivity, arising from the physiological fall of HbA1c by the second trimester, leading to the underestimation of HbA1c.

What about the OR 1.75 thresholds?

While the TOBOGM subgroup analysis supports higher glycaemic thresholds for gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosis in early pregnancy, raising the threshold for the 24-28 week POGTT, we are going to miss some women who will no longer be identified as GDM at 24-28 weeks because of the higher threshold that will be used. These women diagnosed as GDM using the lower threshold are at risk of perinatal complications. The women and their offsprings are also at risk of future cardiometabolic outcomes. The working group agonise over having two separate thresholds and the consensus was to keep the threshold for both the early screening and 24-28 week POGTT the same. We need strategies to identify these women and their offsprings for diabetes screening and diabetes prevention in the future.

References:

- HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group; Metzger BE, Lowe LP, Dyer AR, et al. Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. New Eng J Med 2008; 358:1991-2002

- Nankervis A, McIntyre HD, Moses R, et al. Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society. ADIPS Consensus Guidelines for the Testing and Diagnosis of Hyperglycaemia in Pregnancy in Australia and New Zealand (modified November 2014).

- McIntyre D, Gibbons KS, Ma RCW, et al. Testing for gestational diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. An evaluation of proposed protocols for the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2020; 167: 108353.

- Simmons D, Immanuel J, Hague WM, et al, TOBOGM Research Group. Treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosed early in pregnancy. N Engl J Med 2023; 388: 2132-2144.

- Haque MM, Tannous KW, Herman WH, et al. TOBOGM Consortium. Cost-effectiveness of diagnosis and treatment of early gestational diabetes mellitus: economic evaluation of the TOBOGM study, an international multicenter randomized controlled trial. EClinicalMedicine 2024; 71: 102610

- Crowther CA, Samuel D, McCowan LME, et al. GEMS Trial Group. Lower versus higher glycemic criteria for diagnosis of gestational diabetes. N Engl J Med 2022; 387: 587-598.

- Manerkar K, Crowther CA, Harding JE, et al. Impact of gestational diabetes detection thresholds on infant growth and body composition: a prospective cohort study within a randomized trial. Diabetes Care 2024; 47:56-65.

- Sweeting A, Hare MJ, de Jersey SJ, Shub AL, Zinga J, Foged C, Hall RM, Wong T, Simmons D. Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society (ADIPS) 2025 consensus recommendations for the screening, diagnosis and classification of gestational diabetes. Med J Aust. 2025 Jun 22.