22nd December 2018, Dr Chee L Khoo

Endometriosis is the most frequently diagnosed condition in women with chronic pelvic pain. What if they can’t find endometriosis on laparoscopy? In 60% of women with chronic pelvic pain, the cause remained unknown. A significant proportion of these women may suffer from pelvic congestion syndrome (PVC). Is this one of those “idiopathic” type condition which is diagnosed when all tests are negative? What is PCS?

PCS is also known as pelvic pain syndrome, female varicocele, pelvic vascular congestion, or pelvic venous insufficiency. Whenever a condition is known by so many different names, it often means that we do not fully understand the condition. This was the case with PCS but our understanding of the pathophysiology has progressed a long way. It remains under-diagnosed although there is increasing acceptance and recognition of the condition now. Soysal et al found a 31% incidence of PCS in a population of symptomatic women after evaluation with pelvic examination, laparoscopy, ultrasound and venography (1).

The Venous Plexus

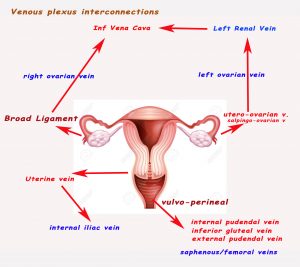

The pelvic congestion is thought to be caused by pelvic venous insufficiency or venous incompetence. To understand the pathophysiology of the venous problem, we need to revise the venous drainage of the pelvic region. The pelvic region is drained by a set of interconnecting plexus of veins. Much of the uterus drain into the ovarian plexus (utero-ovarian and salpingo-ovarian veins) within the broad ligament. The left ovarian plexus drains into the left renal vein which in turn drain into the inferior vena cava. The right ovarian plexus drains usually drains directly into the IVC. Sometimes, it drains into the right renal vein.

The lower uterus and vagina is drained by the uterine veins which drains into the internal iliac veins. The uterine fundus drains either into the ovarian plexus or uterine veins. The vulva and perineal tissues drain into the internal pudendal veins which drain into the inferior gluteal veins and then external pudendal veins. They then drain into either the saphenous veins which we know drains into the femoral veins or directly into the femoral veins.

Venous insufficiency

Pelvic venous congestion is caused by venous insufficiency and venous insufficiency can either be primary or secondary. Primary pelvic (venous) insufficiency can be caused by congenital venous incompetence. Secondary venous insufficiency can also be caused from obstruction (e.g. nutcracker syndrome, May-Thurner syndrome) where the ovarian or pelvic veins are blocked by surrounding arteries.

Ahlberg et al demonstrated that ovarian venous valves are absent congenitally in 15% of the female patients on the left and 6% on the right and valves are incompetent in 41% of the female patients on the left and 46% on the right. Incidence of incompetent valves and increased venous diameter is greater in women (2).

Ovarian varicosities are seen more frequently after pregnancy. The capacity of pelvic veins may increase 60-fold over the non-pregnant state, contributing to both venous dilatation and valvular incompetence. There are unique reasons why pelvic veins are particularly liable to become dilated, even without pregnancy. Many pelvic veins are devoid of valves and have weak attachments between the adventitia and supporting connective tissue.

It is thought that pelvic varicosities causes the pain in pelvic venous congestion although direct evidence of correlation is lacking.

Who to suspect

Patients are often multiparous, pre-menopausal females between 20-40. Symptoms that may be suggestive of PCS include positional lower back, pelvic or upper thigh pain that are non-cyclical. The symptoms may be worse around menses, at the end of the day, after prolonged standing or heavy activity and improve with lying down. There may be associated deep dyspareunia and prolonged post coital discomfort.

Examination may reveal pain with cervical excitation and ovarian tenderness. The combination of post coital ache and ovarian point tenderness is reported to be 94% sensitive and 77% specific for PVI when confirmed by venography (3).

Vulvoperineal varicosities can be found in 4 to 8.6% of the patients (4). These varices can extend over the buttock and posterior-medial thigh and communicate with both greater and lesser saphenous veins. They most commonly manifest during pregnancy and regress postpartum.

Diagnosis

Naturally, we need to exclude endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, postoperative adhesions, and uterine pathology including adenomyosis or leiomyoma. MRI, CT , pelvic ultrasound and laparoscopy are useful in excluding these causes but they all have poor sensitivity for pelvic varicosities. In experienced hands, ultrasound can reveal enlarged ovarian veins greater than 6 mm in diameter with reversed blood flow, presence of pelvic varicocele (>5 mm), and dilated (> 5 mm) arcuate veins crossing the uterine myometrium between pelvic varicoceles. Venographic findings include renal vein reflux into dilated ovarian veins (>5mm), stagnation of contrast in the pelvic veins, contralateral reflux across the midline, and demonstration of vulvoperineal or thigh varices (5).

The treatment of choice

Surgical ovarian vein ligation was first described by Rundqvist in 1984 (5). This was followed by the first case report of endovascular embolization by Edwards et al (6). Ovarian vein embolization is now the treatment of choice for PCS. The largest series of patients with PCS treated with endovascular therapy to date, published by Laborda et al, includes 202 patients with pelvic pain selected from a population of patients with lower extremity venous insufficiency. Clinical benefit was seen in 94% of patients (7). There was a 12.5% recurrence rate. Lasting and significant benefit was documented at 5 years.

The Society of Vascular Surgery has endorsed with a 2B recommendation endovascular treatment of PCS in their published practice guidelines for treatment of chronic venous disease (8).

See a real life case here.

Spectrum Interventional Radiology is equipped with the latest technology, with access to the new Interventional Theatre at Sydney South West Private Hospital located in Liverpool. Refer your patient for consultation and assessment.

Reference

- SoysalME, Soysal S, Vicdan K, Ozer S. A randomized controlled trial of goserelin and medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of pelvic congestion. Hum Reprod 2001;16(5):931–939

- Ahlberg NE, Bartley O, Chidekel N. Right and left gonadal veins. An anatomical and statistical study. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1966; 4(6):593–601

- Beard RW, Reginald PW,Wadsworth J. Clinical features of women with chronic lower abdominal pain and pelvic congestion. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1988;95(2):153–161

- Jung SC, Lee W, Chung JW, et al. Unusual causes of varicose veins in the lower extremities: CT venographic and Doppler US findings. Radiographics 2009;29(2):525–536

- Rundqvist E, Sandholm LE, Larsson G. Treatment of pelvic varicosities causing lower abdominal pain with extraperitoneal resection of the left ovarian vein. Ann Chir Gynaecol 1984;73(6): 339–341

- Edwards RD, Robertson IR, MacLean AB, Hemingway AP. Case report: pelvic pain syndrome — successful treatment of a case by ovarian vein embolization. Clin Radiol 1993;47(6):429–431

- Laborda A,Medrano J, de Blas I, Urtiaga I, Carnevale FC, de Gregorio MA. Endovascular treatment of pelvic congestion syndrome: visual analog scale (VAS) long-term follow-up clinical evaluation in 202 patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2013;36(4): 1006–1014

- Gloviczki P, Comerota AJ, Dalsing MC, et al; Society for Vascular Surgery ; American Venous Forum. The care of patients with varicose veins and associated chronic venous diseases: clinical practice guidelines of the Society for Vascular Surgery and the American Venous Forum. J Vasc Surg 2011;53(5, Suppl): 2S–48S