25th December 2018, Dr Chee L Khoo

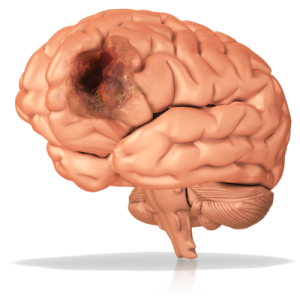

After the acute management of an ischaemic stroke, what follows is the diagnostic process to find the underlying cause and secondary prevention of further strokes. In younger patients and in patients whose atherosclerotic burden is low, the search for a cause can be challenging. Some of the rarer causes of stroke and cardioembolic causes (including atrial fibrillation) needs to be excluded. When an obvious cause is not found, we lump them together under embolic cause of undetermined source (ESUS) or cryptogenic ischaemic stroke. Increasingly, patent foramen ovale (PFO) is diagnosed when investigating embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS) especially in the young stroke patient.

For stroke prevention in patients who had an ischaemic stroke and found to have PFO, we have three choices to prevent recurrent strokes: closure of PFO, anti-platelet therapy or anti-coagulant therapy. Which is better? In patients with PFO who had a stroke, you would think that closure of the foramen would be logical. However, the evidence comparing medical therapy with closure is conflicting. To confuse the matter further, there is debate on which medical therapy is better. Is anti-platelet or anti-coagulation better?

In patients with PFO who suffered an ischaemic stroke, comparison between closure of PFO and medical treatment has been tested in six randomised trials (1–6) with three showing significant reductions for recurrent stroke. Two meta-analyses showed better efficacy with closure compared with medical therapy. (7,8).

We know that oral anti-coagulation therapy (OACT) is superior to anti-platelet therapy (APT) when treating venous thromboembolism. Since stroke related to PFO is thought to be primarily a consequence of embolism originating as a venous thrombus, it would be logical to think that OACT should be superior to APT in stroke prevention in patients with PFO. However, data directly comparing APT with OACT is limited.

In a network meta-analysis of 6 randomised controlled trials consisting of 3,497 patients, PFO closure, anti-platelet and anti-coagulant therapies were compared (9). Both PFO closure and OACT were equally effective in preventing strokes but PFO closure had the highest top rank probability of atrial fibrillation and OAT had the highest risk of bleeding complications.

The NAVIGATE ESUS trial was a double-blinded, randomised, phase 3 trial done at 459 centres in 31 countries that assessed the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban versus aspirin for secondary stroke prevention in patients with ESUS (10). Eligible patients were those with recent (7 days – 6 months) ischaemic stroke confirmed by neuroimaging. There must be no extra-cranial atherosclerosis >50% in arteries supplying the area of the stroke.

The primary efficacy outcome was time to recurrent ischaemic stroke between treatment groups. The primary safety outcome was major bleeding. Between Dec 23, 2014, and Sept 20, 2017, 7213 participants were enrolled and assigned to receive rivaroxaban or aspirin. The trial was terminated early because of the absence of efficacy in the overall study population. Although rivaroxaban was superior to aspirin in lowering the risk of recurrent stroke, the result was not statistically significant. Rivaroxaban cause more major bleeding compared with aspirin but that was not significant either.

The jury is somewhat out as to what is the optimal treatment of choice for patients with ESUS who are found to have PFO. Some of the trials have found that closure of the PFO is superior to medical treatment will others have shown a trend towards superiority but not statistically significant. If one does not go for closure, then there is a choice between anti-platelet therapy or anti-coagulant therapy. The data comparing either medical therapy is limited but from what limited data we have, there is a trend towards superiority with anti-coagulant therapy with anti-coagulant therapy but not statistically significant. As usual, we need more targeted studies. In the meantime, The Risk of Paradoxical Embolism (RoPE) score, can be used to predict the probability of stroke-related PFO

Access the abstract here.

References:

- 1 Furlan AJ, Reisman M, Massaro J, et al. Closure or medical therapy for cryptogenic stroke with patent foramen ovale. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 991–99.

- 2 Saver JL, Carroll JD, Thaler DE, et al. Long-term outcomes of patent foramen ovale closure or medical therapy after stroke. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1022–32.

- 3 Meier B, Kalesan B, Mattle HP, et al. Percutaneous closure of patent foramen ovale in cryptogenic embolism. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 1083–91.

- 4 Sondergaard L, Kasner SE, Rhodes JF, et al. Patent foramen ovale closure or antiplatelet therapy for cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1033–42.

- 5 Mas JL, Derumeaux G, Guillon B, et al. Patent foramen ovale closure or anticoagulation vs. antiplatelets after stroke. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1011–21.

- 6 Lee PH, Song J-K, Kim JS, et al. Cryptogenic stroke and high-risk patent foramen ovale: the DEFENSE-PFO Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71: 2335–42.

- Riaz H, Khan MS, Schenone AL, Waheed AA, Khan AR, Krasuski RA. Transcatheter closure of patent foramen ovale following cryptogenic stroke: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am Heart J 2018; 199: 44–50.

- Smer A, Salih M, Mahfood Haddad T, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on patent foramen ovale closure versus medical therapy for secondary prevention of cryptogenic stroke. Am J Cardiol 2018; 121: 1393–99.

- Saber H, Palla M, Kazemlou S, Azarpazhooh MR, Seraji-Bozorgzad N, Behrouz R. Network meta-analysis of patent foramen ovale management strategies in cryptogenic stroke. Neurology 2018; 91: e1–7.

- Scott E Kasner, Balakumar Swaminathan, Pablo Lavados, et al. Rivaroxaban or aspirin for patent foramen ovale and embolic stroke of undetermined source: a prespecified subgroup analysis from the NAVIGATE ESUS trial. Lancet Neurol 2018; 17: 1053–60