26th February 2022, Dr Chee L Khoo

We all know that, in theory, exercises are always good for our patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) in more ways than one. There are a few problems though, when putting theory into practice. Most of our patients with T2D not only don’t exercise regularly, they actually don’t know what exercise to do, how they should do it for and how often they are supposed to be doing them. As the doctor prescribing those exercises, it is incumbent upon us to be precise and clear in what they are supposed to be doing. It is no longer sufficient to instruct your patients to “walk more”, “park your car further” or “increase the number of steps” as an exercise prescription. They are just as good as “eat less” advice to these patients. What is the correct advice?

Lifestyle interventions and/or medications are usually prescribed for comprehensive management of T2D. More recently, bariatric surgery has also become part of a possible treatment plan together with medical nutrition therapy. We are now also aiming for diabetes remission in all our patients if possible. Unfortunately, often we pay lip service to exercise. Physical activity (PA) not only improve glucose, lipid and blood pressure parameters and reduce both macro and microvascular complications but it helps improve quality of life and maintain weight loss in these patients.

During any type of PA, glucose uptake into active skeletal muscles increases via insulin-independent pathways. Blood glucose levels are maintained by increases in hepatic gluconeogenesis and mobilisation of free fatty acids which are usually impaired in patients with T2D. Improvements in systemic, and possibly hepatic, insulin sensitivity after any PA can last from 2 to 72 h, with reductions in blood glucose closely associated with PA duration and intensity (1-3). In addition, regular PA enhances β-cell function, insulin sensitivity, vascular function , and gut microbiota, all of which may lead to better diabetes and health management as well as disease risk reduction. Many of the proven benefits result from improved insulin sensitivity, postprandial hyperglycaemia, and CVD risk.

Thus, what exercises do what?

Aerobic exercise

Short-term aerobic exercise training improves insulin sensitivity in adults with T2D, paralleling

improved mitochondrial function. Vigorous aerobic exercise training for 7 days may improve glycaemia increased insulin-stimulated glucose disposal and suppression of hepatic gluconeogenesis. In patients with T2D and obesity, short-term aerobic exercise improves whole-body peripheral insulin sensitivity. Regular aerobic exercise training leads to fewer daily hyperglycaemic excursions. The improvements in insulin sensitivity, lipids, blood pressure, other metabolic parameters and fitness levels occur even without weight loss (4,5).

Resistance exercise

Aerobic exercise in combination with lower calorie intake (whether from bariatric surgery or MNT) leads to weight loss but some of the weight loss include skeletal muscle loss. This is particularly evident in non-Caucasian patients with mild or modest obesity. Resistance exercise training in

adults with T2D can result in 10%–15% improvements in strength, bone mineral density, blood pressure, lipid profiles, skeletal muscle mass, and insulin sensitivity (6). Not surprisingly, resistance training increases lean skeletal muscle mass and reduce A1C threefold more in older adults with T2D compared with a calorie-restricted, non-exercising group that lost skeletal muscle mass (7).

Combined aerobic and resistance exercise training is superior to either mode alone. Combined exercise modalities result in greater weight loss, better glycaemic improvements and better insulin sensitivity improvements (8).

Higher intensity interval training (HIIT)

HIIT is a regimen that involves aerobic training done between 65% and 90% V˙ O2peak or 75% and 95% heart rate peak for 10 s to 4 min with 12 s to 5 min of active or passive recovery. HIIT has gained attention as a potentially time-efficient modality that can elicit significant physiological and metabolic adaptations. HIIT result in greater fitness, better body composition, and improved

continuous glucose monitor–monitored glycemia (9), as well as enhanced insulin sensitivity and pancreatic β-cell function in adults with T2D (10). HIIT also result in enhanced diastolic function (11), increased left ventricular wall mass, greater end-diastolic blood volume due to increased stroke volume and left ventricular ejection fraction (12), and improved endothelial function (13).

Individuals with T2D who seek to improve glycaemia with HIIT should closely monitor their responses to training, as chronic intense training may have negative effects such as transient postexercise hyperglycaemia and soft tissue injuries. HIIT is gruesome and is not easy. HIIT is not for everyone.

T2D prevention

We know that weight loss from intensive lifestyle interventions reduces T2D risk but even among those failing to meet the weight loss goal of 7% during the first year, individuals meeting the PA goal had a 44% reduction in diabetes incidence, independent of the small weight loss (−2.9 kg) (14).

GDM Prevention

Women with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) may have a nearly 10-fold higher risk of developing T2D at some point. PA is a preventative tool for GDM and subsequent development of T2D. Pre-pregnancy exercise training has been consistently associated with a reduced risk of GDM.

Physical activity can also improve mental health and cognitive function in patients with T2D.

For most individuals planning to participate in a low- to moderate-intensity PA like brisk walking, no pre-exercise medical evaluation is needed unless symptoms of CVD or microvascular complications are present. In adults who are currently sedentary, medical clearance is recommended before participation in moderate- to high-intensity PA. Although suggested by practice guidelines, pre-exercise stress testing in asymptomatic adults with T2D remains controversial.

The consensus statement update

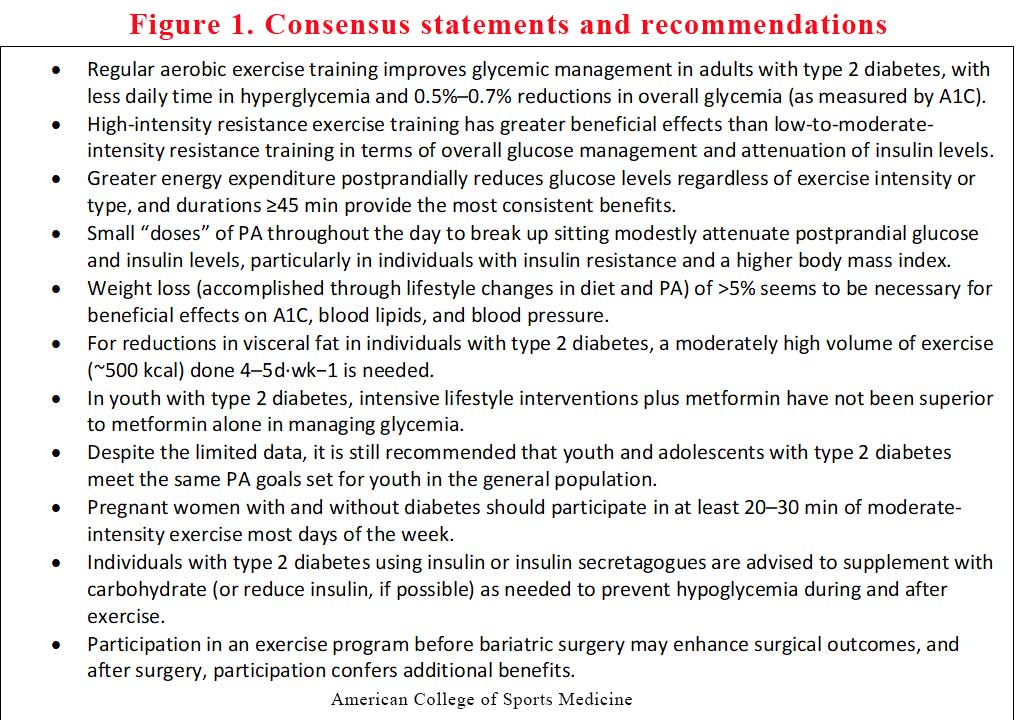

The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) (15,16) published a joint position stand on exercises recommendations for patients with T2D. The ACSM recently published an update to the 2010 position statement due to the considerable amount of research over the last decade of so. Figure 1 is an adaptation of their published update.

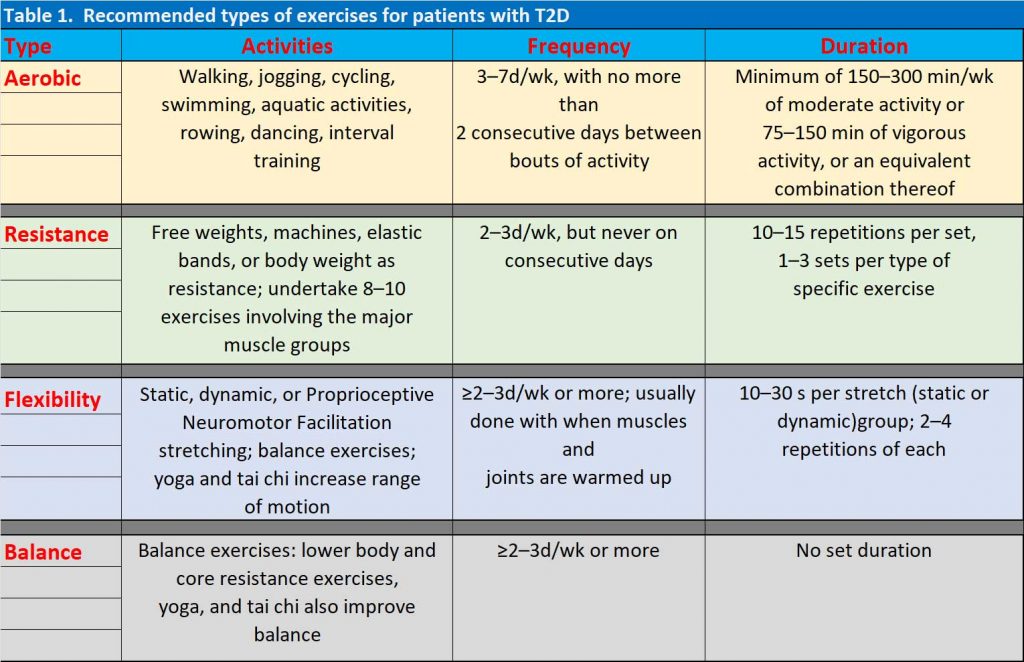

Of note, is the incorporation of flexibility and balance exercises into their recommendations. You now have a set of detailed recommendations for your patients with T2D when you discuss their exercise prescription. Table 1 is a summary of those details.

References:

- Bajpeyi S, Tanner CJ, Slentz CA, et al. Effect of exercise intensity and volume on persistence of insulin sensitivity during training cessation. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2009;106(4):1079–85.

- Houmard JA, Tanner CJ, Slentz CA, Duscha BD, McCartney JS, Kraus WE. Effect of the volume and intensity of exercise training on insulin sensitivity. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2004;96(1):101–6.

- Kang J, Robertson RJ, Hagberg JM, et al. Effect of exercise intensity on glucose and insulin metabolism in obese individuals and obese NIDDM patients. Diabetes Care. 1996;19(4):341–9.

- Kadoglou NP, Iliadis F, Angelopoulou N, et al. The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise training in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14(6):837–43.

- Boulé NG, Kenny GP, Haddad E, Wells GA, Sigal RJ. Metaanalysis of the effect of structured exercise training on cardiorespiratory fitness in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2003;46(8):1071–81.

- Gordon BA, Benson AC, Bird SR, Fraser SF. Resistance training improves metabolic health in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;83(2):157–75.

- Dunstan DW, Daly RM, Owen N, et al. High-intensity resistance training improves glycemic control in older patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(10):1729–36.

- Schwingshackl L, Missbach B, Dias S, Konig J, Hoffmann G. Impact of different training modalities on glycaemic control and blood lipids in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2014;57(9):1789–97.

- KarstoftK,Winding K,Knudsen SH, et al. The effects of free-living interval-walking training on glycemic control, body composition, and physical fitness in type 2 diabetic patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(2):228–36.

- Nieuwoudt S, Fealy CE, Foucher JA, et al. Functional high-intensity training improves pancreatic β-cell function in adults with type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2017;313(3):E314–E20.

- Hollekim-Strand SM, Bjorgaas MR, Albrektsen G, Tjonna AE, Wisloff U, Ingul CB.High-intensity interval exercise effectively improves cardiac function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and diastolic dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(16):1758–60.

- Revdal A, Hollekim-Strand SM, Ingul CB. Can time efficient exercise improve cardiometabolic risk factors in type 2 diabetes? A pilot study. J Sports Sci Med. 2016;15(2):308–13.

- Ghardashi Afousi A, Izadi MR, Rakhshan K, Mafi F, Biglari S, Gandomkar Bagheri H. Improved brachial artery shear patterns and increased flow-mediated dilatation after low-volume highintensity interval training in type 2 diabetes. Exp Physiol. 2018; 103(9):1264–76.

- Hamman RF, Wing RR, Edelstein SL, et al. Effect of weight loss with lifestyle intervention on risk of diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(9):2102–7.

- Colberg SR, Albright AL, Blissmer BJ, et al. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: American College of SportsMedicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Exercise and type 2 diabetes. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(12):2282–303.

- Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, et al. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American College of SportsMedicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Diabetes Care. 2010; 33(12):e147–67.