27th February 2022, Dr Chee L Khoo

Homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia (HoFH) is one of those conditions that allow us to prescribe the new PCSK9 inhibitors under PBS Authority. It is a pretty rare inherited disorder resulting in extremely elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL) levels and significantly elevated risk of premature atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). Despite the extreme high risks, HoFH is usually go unrecognised and if recognised are diagnosed late and undertreated. Although the prevalence of HoFH was traditionally estimated to be approximately 1 in 1 million, more recent studies have suggested a prevalence closer to 1 in 300 000. You might question why I am writing about HoFH and what we can learn from this rare condition.

The most severe form of familial hypercholesterolaemia is HoFH which broadly comprises simple homozygous as well as compound and double heterozygous cases. LDL cholesterol levels might exceed 20 mmol/L depending on the variants carried; patients with an LDLR variant that leads to no residual functional protein (LDLR-negative variant) in both alleles are generally the most severely affected. The magnitude and duration of exposure to extreme LDL cholesterol levels largely determines prognosis. Standard maximum statins plus ezetimibe are often insufficient to bring these patients to target. Some patients require extra-corporeal removal of LDL-C (lipoprotein apheresis).

The HoFH International Clinical Collaborators registry is the first and only global HoFH registry initiated by physicians looking after HoFH patients in specialised centres across the globe. It offers a unique opportunity to provide a comprehensive assessment of the genetic profile and clinical characteristics of HoFH patients globally and provide a framework to inform the development of international clinical guidelines for the management of this high-risk condition. More importantly, by seeing what early intervention can do to reduce the mortality and morbidity associated with HoFH, we can use lessons learnt to apply to our patients with hypercholesterolaemia with high cardiovascular risks.

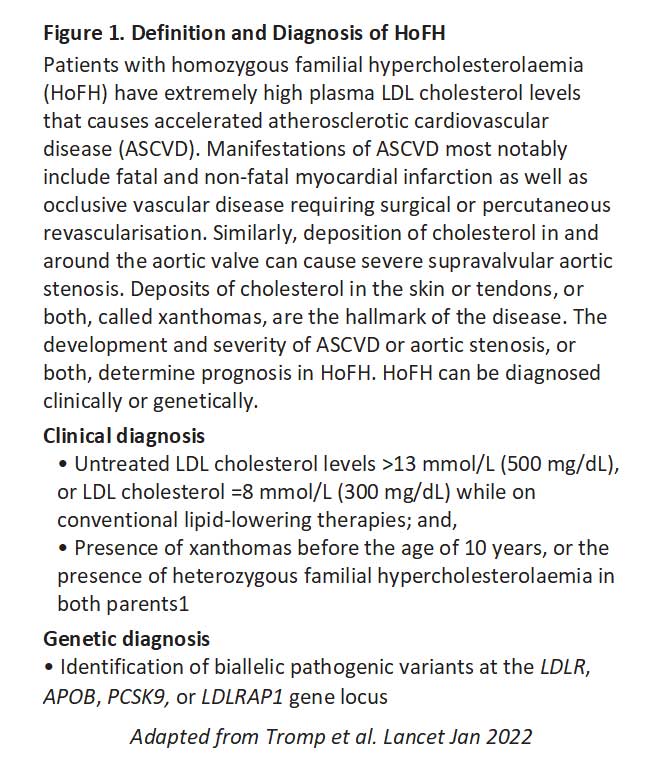

Patients are eligible for inclusion into the registry if they had received a clinical or genetic diagnosis of HoFH by the treating clinician (see Figure 1). Where genetic testing was reported, patients were considered HoFH if they were found to carry biallelic familial hypercholesterolaemia variants (either homozygous, compound heterozygous, or double heterozygous)

The registry recently published data from its retrospective cohort study of HoFH patients. Data on 751 patients from 88 institutions across 38 countries representing all seven World Bank regions were available (1). 20 countries were classified as high-income, 12 as upper-middle-income, and six as lower-middle-income countries.

The median age of diagnosis was 12∙0 years. Race was reported for 527 patients – 64% patients were White, 23% were Asian, and 13% were Black or mixed race. Patients from high-income countries, compared with those from non-high-income countries, were older at the time of diagnosis (16∙0 years vs 10∙0 years) and had fewer physical stigmata such as xanthomas (64% vs 74%) at the time of diagnosis.

Overall, untreated LDL cholesterol levels were 14∙7 mmol/L. Patients who had a genetic diagnosis had lower untreated LDL cholesterol levels (14·2 mmol/L) and presented less frequently with xanthomas at diagnosis (66%), as compared with patients who had a clinical diagnosis only (LDL cholesterol 16·1 mmol/L, xanthomas at diagnosis (76%).

Nearly all patients (92%) were on statin therapy, usually high intensity (83%) where statin dosage was available, defined as atorvastatin 40 mg or more or rosuvastatin 20 mg or more per day. Ezetimibe was used by 72% of patients from high-income countries, and 54% from non-high-income countries. Lipid lowering therapy (LLTs) such as PCSK9 inhibitors, lomitapide, and evinacumab were used infrequently and predominantly in patients from high-income countries. Lipoprotein apheresis (including plasma exchange) was done in 39% of patients, initiated at a median age of 15∙0 years. Patients on apheresis had higher untreated LDL cholesterol at diagnosis (17·2 mmol/L) compared with patients who were not on apheresis (13·5 mmol/L).

Despite multiple therapies, very few individuals achieve guideline recommended LDL cholesterol levels. Overall, 12%of patients reached an LDL cholesterol of less than 2·6 mmol/L for primary prevention or <1·8 mmol/L for secondary prevention. 30% in patients were on monotherapy, 45% with two classes of LLT and more than 65% in patients using three or more LLT. The more LLT patients were on, the more likely they attained LDL cholesterol goals. LDL goals were more frequently attained in patients from high-income countries (21%) compared with non-high-income countries (3%).

Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACE)

The median age at which MACE occurred was 31·0 years with 9% of patients already having suffered a non-fatal myocardial infarction, having undergone PCI or CABG or with aortic valve stenosis at diagnosis of HoFH. There were 37 deaths, of which 76% were from cardiovascular causes (median 28·0 years). The earliest recorded age at which angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, CABG, or PCI were reported were 4 years, 10 years, 5 years and 10 years respectively. Peripheral artery disease occurred in 6% of patients and cerebrovascular disease in 3% of patients.

Supravalvular aortic stenosis was reported in 29% of patients. Where echocardiographic data were available 13% patients had mild, 9% moderate and 3% severe aortic stenosis.

This retrospective cohort study shows how aggressive extreme high LDL-C can be in causing very premature cardiovascular events. Diagnosing HoFH in the second decade of life is too late, because by this age many patients have already had cardiovascular complications, supporting the need for more effective strategies to aid timely diagnosis, such as systematic cascade screening or universal screening at an early age.

Despite the use of LLT, first MACE occurs early at a median age of 31 years, and in 4% of patients before the age of 18 years, in line with anecdotal evidence that cardiovascular events can occur in HoFH during childhood (2).

In addition to statins and ezetimibe, we now have PCSK9 inhibitors available under the PBS authority for patients with HoFH as well as those at high risk of MACE. Like most things in medicine, early recognition and diagnosis is vital. Perhaps, a referral to your local lipid clinic might be appropriate if you are unsure about the diagnosis or management.

Reference:

- Tromp TR, Hartgers ML, Hovingh GK, Vallejo-Vaz AJ, Ray KK, Soran H, Freiberger T, Bertolini S, Harada-Shiba M, Blom DJ, Raal FJ, Cuchel M; Homozygous Familial Hypercholesterolaemia International Clinical Collaborators. Worldwide experience of homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2022 Feb 19;399(10326):719-728. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02001-8.

- Widhalm K, Benke IM, Fritz M, et al. Homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: summarized case reports. Atherosclerosis 2017; 257: 86–89.