4th January 2023, Dr Chee L Khoo

The term non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) was first coined by Ludwig in 1980. It was rather an exclusive diagnostic term to exclude the other liver disease from being included in the definition. If your liver disease relates to excessive alcohol intake, drugs or autoimmune conditions, it cannot be included in the diagnosis. The aetiology back then was less understood. However, it did exclude those patients with both a NAFLD and another hepatic pathology. In 2020, a panel of international experts reached a consensus that recommended the term “metabolic (dysfunction) -associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD)” as a more appropriate name to describe fatty liver disease associated with metabolic dysfunction, ultimately suggesting that the term NAFLD does not reflect current knowledge (1). NAFLD and MAFLD are not identical disease entities. It’s not just a matter of a name change but there are important differences between them. There is a lot of overlap between them.

There is such a lot to “learn” about MAFLD that we will only be discussing about the definition and the diagnosis of MAFLD this week. In part 2, we will explore the many associated conditions that come with NAFLD and MAFLD. It’s not just liver complications we have to contend with in NAFLD or MAFLD.

NAFLD

NAFLD is the most common cause of chronic liver disease worldwide [2]. It is estimated that 25% of the world’s populations have NAFLD, with the highest prevalence rates in the Middle East and South America. NAFLD is defined as the evidence of steatosis in >5% of hepatocytes detected by imaging techniques or histology. It is an exclusive arrangement though, as the diagnosis of NAFLD is only made in the absence of known causes such as excessive alcohol, viral hepatitis, hereditary liver diseases, or medications that causes fatty liver.

What is excessive alcohol is still being debated but, for now, is defined as >21 standard drinks/week for men and >14 for women in the USA, >30 g daily for men and >20 g for women in UK and EU, >140 g/week for men and >70 g/week for women in Asia-Pacific.

We used to (actually, many still do) think that NAFLD was a benign disease. “You have a little bit of fatty liver”. The concept that NAFL is a benign disease was challenged with the accumulation of evidence. It is now regarded as a progressive disease. Recent data suggest that nearly 25% of the patients with NAFL may develop fibrosis (3). Of course, many of these progress to frank liver cirrhosis.

The definition and diagnosis of NAFLD

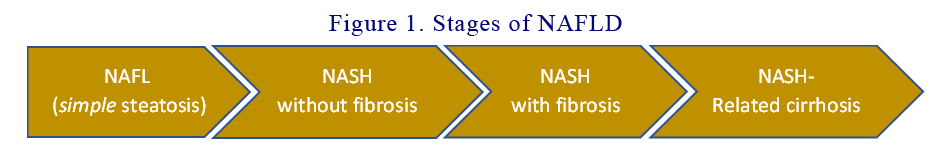

NAFLD is a generic term that encompasses the spectrum of non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL), non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and NASH-related cirrhosis. NASH is the inflammatory subtype of NAFLD, and it is characterised by steatosis, evidence of hepatocyte injury (ballooning), and inflammation with or without fibrosis. NASH-cirrhosis is the presence of cirrhosis with current or previous histological evidence of steatosis or steatohepatitis. Patients with NAFLD show a stepwise increase in mortality rates according to the fibrosis stage (4) and therefore, the severity of hepatic fibrosis is currently recognised as the main prognostic determinant in this clinical entity. The 4 stages in NAFLD (see Figure 1) are:

- NAFLD (simple steatosis)

- Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) without fibrosis

- Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) with fibrosis

- NASH-related cirrhosis

The pathophysiology of NAFLD/NASH/Cirrhosis and MAFLD

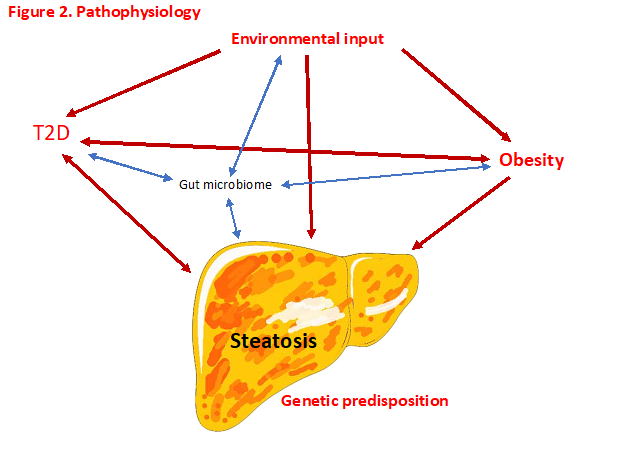

The pathophysiology of NAFLD is complex and multifactorial with multiple systemic alterations involved. It is now thought that a “multiple-parallel hits” hypothesis could represent the process of NAFLD development and progression, where various factors act in parallel and in a synergic manner in subjects with genetic predisposition. This multiple-hits hypothesis is based on the concept that genetic and environmental factors associated with dietary habits lead to obesity, insulin resistance development, and alteration of intestinal microbiome. We know many of these “environmental” factors – glucotoxicity, lipotoxicity and obesity. These factors act in parallel and in a synergistic manner.

Insulin resistance promotes hepatic de novo lipogenesis and adipose tissue lipolysis, leading to an increased flux of fatty acids to the liver. Insulin resistance will also lead to adipose tissue dysfunction inducing secretion of inflammatory cytokines.

Intrahepatic accumulation of fatty acids will induce the development of several deleterious phenomena such as mitochondrial dysfunction, endoplasmic reticulum stress, oxidative stress and production of reactive oxygen species.

Genome-wide association study (GWAS) have identified the main risk variants of the NAFLD population (6). Currently, at least five variants in different genes are robustly associated with the susceptibility to the progression of NAFLD. They are PNPLA3, TM6SF2, GCKR, MBOAT7, and HSD17B13[ (7-9). Some of the variants share the same predisposition to insulin resistance, T2D and obesity. Further, some variants are associated with increased susceptibility to steatosis with viral hepatitis. See Figure 2.

Whereas liver biopsy is required for the diagnosis of NASH, NAFLD can also be evaluated non-invasively by imaging techniques such as ultrasound, CT or MRI. Transient elastography (e.g. FibroScan) is being widely used combined with different scores, such as NAFLD fibrosis score (NFS) or Fibrosis-4 (FIB4) index, to better predict the severity of hepatic injury. FibroScan has a sensitivity of 85% for detecting advanced fibrosis and 92% for detecting cirrhosis.

Keep in mind that while ultrasound is the most widely used first-line diagnostic modality, ultrasound does not reliably detect steatosis of <20%, and its performance is suboptimal in individuals with body mass index (BMI) >40 kg/m2.

Pending appropriate validation from future research, serum biomarkers of steatosis could replace imaging methods.

The definition of MAFLD

As you can see, the definition of NAFLD is a negative diagnosis – steatosis not caused by the above conditions. The term encompasses a continuum of liver abnormalities with a myriad of aetiologies which makes data comparison difficult and thence, treatment efficacy difficult to assess. The gold standard of diagnosis is liver biopsy which, as you can imagine, not always easy to obtain.

There is a very strong inter-relation and synergy between dysmetabolism and hepatic steatosis both in its aetiology and complications. In 2020, a panel of international experts from 22 countries propose a new definition for the diagnosis of MAFLD that is both comprehensive and simple and is independent of other liver diseases (1). The criteria for a positive diagnosis of:

MAFLD based on histological (biopsy), imaging or blood biomarker evidence of fat accumulation in the liver (hepatic steatosis) and one of the following three criteria:

- Overweight/obesity

- Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) or

- “Evidence of metabolic dysregulation”

The “evidence of metabolic dysregulation” has been defined as having at least 2 of the following:

- Waist circumference ≥102/88 cm in Caucasian men and women (or ≥90/80 cm in Asian men

- and women)

- Blood pressure ≥130/85 mmHg or specific drug treatment

- Plasma triglycerides ≥150 mg/dl (≥1.70 mmol/L) or specific drug treatment

- Plasma HDL-cholesterol <40 mg/dl (<1.0 mmol/L) for men and <50 mg/dl (<1.3 mmol/L) for

- women or specific drug treatment

- Prediabetes (i.e., fasting glucose levels 5.6 to 6.9 mmol/L, or 2-hour post-load

- glucose levels 7.8 to 11.0 mmol or HbA1c 5.7% to 6.4%

- Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance score ≥2.5

- Plasma high-sensitivity C-reactive protein level >2 mg/L

The above list is not that foreign to us as they are just the normal list we see in patients with elements of metabolic syndrome. You will also notice a fair bit of overlap and intimate relationship between the two conditions. Indeed, not surprisingly, 70% of patients with T2D have MAFLD. Which reminds us to look for MAFLD in our patients with metabolic syndrome, obesity and T2D.

The bit about metabolic dysregulation is particularly relevant in the lean MAFLD patients – patients who are truly lean with minimal or no obesity nor increased waist circumference. Importantly, the exclusion of alternative causes of chronic liver disease, such as alcohol or viral hepatitis, are no longer required to diagnose MAFLD.

You would have noticed that there isn’t any comment on staging MAFLD like we do for NAFLD. Disease severity is thought to be best described by the grade of activity and the stage of fibrosis. Like most other chronic diseases, MAFLD activity grade should be considered a continuum rather than the current dichotomous stratification into steatohepatitis and non-steatohepatitis. In time, with improved case identification, histological changes can be linked to disease status with their relevant impacts on the disease course. Ultimately, future non-invasive tests and blood markers capturing both disease activity and fibrosis stage can be further validated where disease categorisation possible.

What about cryptogenic cirrhosis?

In advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis, steatosis and necro-inflammatory reactions may disappear; this condition is known as burn-out NASH. Patients with this presentation used to be called cryptogenic cirrhosis. A study that compared 103 and 144 patients with cryptogenic cirrhosis and biopsy-proven NASH, respectively, reported that cryptogenic cirrhosis was demographically similar to NASH-related cirrhosis (5). Were all these cryptogenic cirrhosis not cryptogenic after all?

It is proposed that MAFLD-related cirrhosis be considered in patients with cirrhosis in the absence of typical histological signs suggestive of steatohepatitis but who meet at least one of the following criteria: past or present evidence of metabolic risk factors that meet the criteria to diagnose MAFLD with at least one of the following: i) documentation of MAFLD on a previous liver biopsy ii) historical documentation of steatosis by hepatic imaging.

A positive diagnosis finally?

One of the most important differences between NAFLD and MAFLD is the exclusion of alcohol-associated fatty liver disease based on current criteria for alcohol use disorder, viral infections (HIV, HBV or HCV), drug-induced liver injury, autoimmune hepatitis either at baseline or at follow-up is no longer a prerequisite for diagnosis. We already discussed how difficult it is to ascertain what is a safe level of alcohol intake and often, objective measures of the true amount of alcohol intake can be difficult. Besides, there is no reason why MAFLD cannot co-exist with other liver disease and often, patients can have both.

“Secondary” causes of steatosis?

The expert panel also suggest avoidance of the term secondary causes of steatosis as all steatosis are secondary anyway. Instead, we should refer to alternative causes of steatosis when we refer to conditions such as: medications (corticosteroids, valproic acid, tamoxifen, methotrexate, and amiodarone), coeliac disease, starvation, total parenteral nutrition, severe surgical weight loss or disorders of lipid metabolism (abetalipoproteinemia, hypobetalipoproteinemia, lysosomal acid lipase deficiency, familial combined hyperlipidaemia, lipodystrophy, Weber–Christian syndrome, glycogen storage disease, Wilson disease).

In summary, whether you think about NAFLD or MAFLD, the incidence of both is increasing worldwide. Neither conditions are benign and many do progress towards fibrosis and ultimately, cirrhosis. Many of these patients progressed during their time in primary care and it is important that we diagnose them early and mitigate their risks of progression. NAFLD/MAFLD is essentially the liver complication of insulin resistance and T2D. One of the ideas pushing the adoption of the broader MAFLD over the exclusive NAFLD is to remind clinicians to be broader in their comprehensive management of this deadly condition. We will look at what else we need to consider apart from liver complications in our next issue.

References:

- Eslam M, Newsome PN, Sarin SK, et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. 2020 Jul;73(1):202-209. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.039.

- Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, et al. Global epidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology 2016;64:73–84. doi: 10.1002/hep.28431.10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.039

- Mazzolini G, Sowa JP, Atorrasagasti C, Kucukoglu O, Syn WK, Canbay A. Significance of simple steatosis: An update on the clinical and molecular evidence. Cells 2020;9.

- Sanyal AJ, Van Natta ML, Clark J, et al. Prospective study of outcomes in adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med 2021;385:1559-1569.

- Younossi Z, Stepanova M, Sanyal AJ, et al. The conundrum of cryptogenic cirrhosis: Adverse outcomes without treatment options. J Hepatol 2018;69:1365-1370.

- Eslam M, Valenti L, Romeo S. Genetics and epigenetics of NAFLD and NASH: clinical impact. J Hepatol 2018;68:268–279. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.09.003.

- Speliotes EK, Yerges-Armstrong LM, Wu J, Hernaez R, Kim LJ, Palmer CD, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies variants associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease that have distinct effects on metabolic traits. Plos Genet 2011;7:e1001324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001324.

- Kozlitina J, Smagris E, Stender S, Nordestgaard BG, Zhou HH, Tybjærg-Hansen A, et al. Exome-wide association study identifies a TM6SF2 variant that confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Genet 2014;46:352–356. doi: 10.1038/ng.2901.

- Abul-Husn NS, Cheng X, Li AH, Xin Y, Schurmann C, Stevis P, et al. A protein-truncating HSD17B13 variant and protection from chronic liver disease. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1096–1106. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1712191.