14th November 2023, A/Prof Chee L Khoo

Obesity is a recognised risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD). We are all used to treating cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia and diabetes in an attempt to reduce CV events. We should also treat the obesity, shouldn’t we? Logically, weight reduction should lead to reduction in CV events but, unfortunately, lifestyle changes and pharmacological interventions to reduce obesity have not been shown to improve cardiovascular outcomes (1-5). We know that the newer GLP1RAs are potent glucose lowering agents as well as great in weight reduction. We know that our SGLT2 inhibitors have great cardiovascular benefits but what about the GLP1Ras?

The older, first generation GLP1RA, exenatide, was shown to efficacy and cardiovascular safety. The LEADER trial showed that liraglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonist, was superior to placebo in improving glycaemic control and reducing CV events in patients with DM2 and high CV risk. SUSTAIN 6 (semaglutide), REWIND (dulaglutide) and HARMONY (albiglutide) all showed cardiovascular benefit albeit mostly in patients with established CVD or at least at high risk of CVD. These trials recruited patients with diabetes and obesity. Thus, is the CV benefit the result of glycaemic improvement or obesity improvement or both? Do GLP1RAs specifically improve cardiovascular outcomes in patients on its own without improvement in glucose control?

In the Semaglutide Effects on Cardiovascular Outcomes in People with Overweight or Obesity (SELECT) trial, they explored whether the addition of semaglutide 2.4mg to standard care would be superior to placebo in reducing the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events among patients with overweight or obesity and preexisting cardiovascular disease who did not have diabetes. The findings were published just three days ago in the NEJM (6).

SELECT was a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, event-driven superiority trial at 804 clinical sites in 41 countries. Patients were eligible for enrolment if they were

- 45 years of age or older

- Had a BMI ≥ 27

- Had established cardiovascular disease*.

*Cardiovascular disease was defined as previous myocardial infarction, previous stroke, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease.

Key exclusion criteria were a previous diagnosis of diabetes, a glycated haemoglobin level of 6.5% (48 mmol per mole) or higher measured at screening, treatment with any glucose lowering medication or GLP-1 receptor agonist within the previous 90 days, New York Heart Association class IV heart failure, or end-stage kidney disease or dialysis. They specifically did not want anyone with diabetes so that the outcomes cannot be related to improvement in glycaemic control.

Subjects were randomised in a blinded 1:1 manner to either 2.4mg semaglutide or placebo. The primary cardiovascular efficacy end point was a composite of death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke, assessed in a time-to-first-event analysis. This is the standard major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) outcome. Confirmatory secondary end points, assessed in time-to-first-event analyses and tested in hierarchical order, were death from cardiovascular causes, a composite heart failure end point (death from cardiovascular causes or hospitalisation or an urgent medical visit for heart failure), and death from any cause. 17,604 patients were recruited and followed up for 59 months.

At baseline, the mean (±SD) age of the patients was 61.6±8.9 years, 72.3% were male and the mean BMI was 33.3±5.0. The mean HbA1c was 5.8% but 64% had HbA1c between 5.7-6.4% which puts into the prediabetes range. More than three quarters of the patients had had a previous myocardial infarction, and nearly one quarter had chronic heart failure. Thus, although these patients did not have diabetes, they had pretty high CV risks. They do represent many of our typical patients with prediabetes.

Most of the subjects are already on guideline based medical therapy. Most of the patients were receiving lipid-lowering medications (90.1%) and platelet-aggregation inhibitors (86.2%), 70.2% of the patients were taking beta-blockers, 45.0% were taking angiotensin-converting–enzyme inhibitors, and 29.5% were taking angiotensin-receptor blockers.

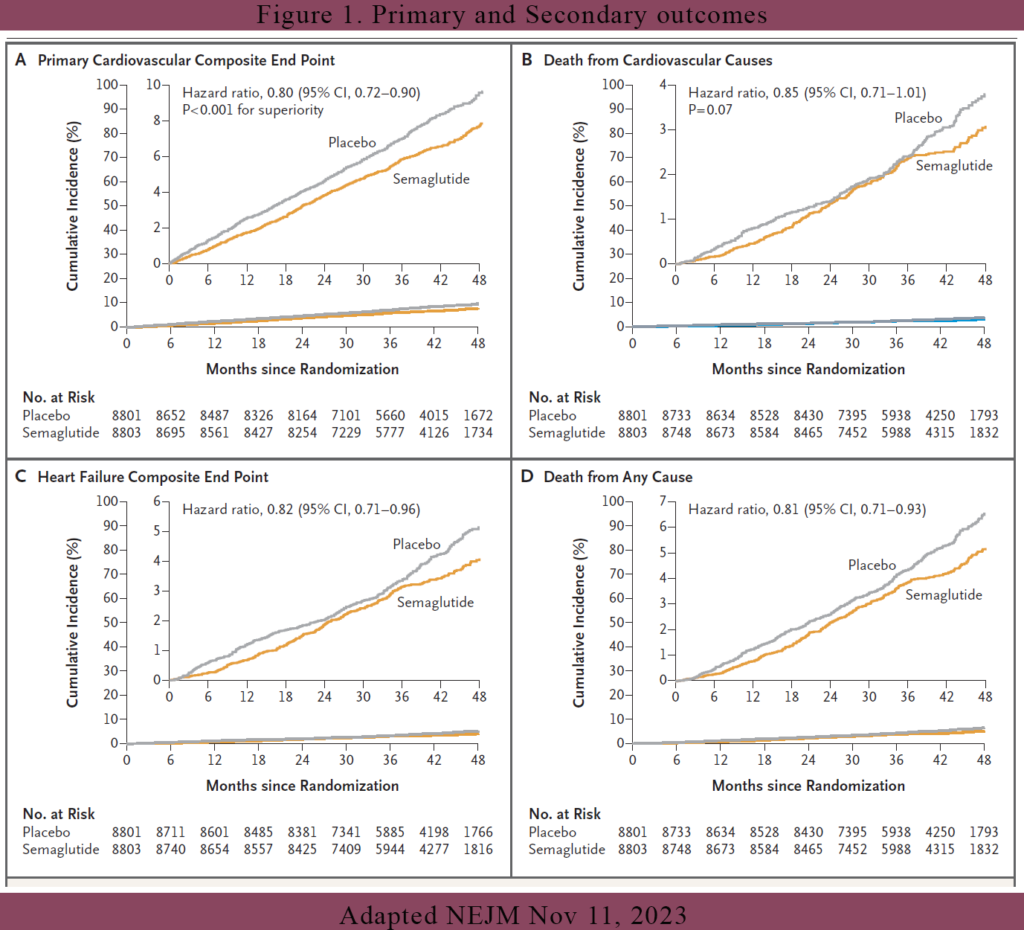

Results (see Figure 1)

CV end points

The primary cardiovascular end-point event (death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke) occurred in 569 of the 8803 patients (6.5%) in the semaglutide group and 701 of the 8801 patients (8.0%) in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.80; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.72 to 0.90; P<0.001). Death from cardiovascular causes, the first confirmatory secondary end point, occurred in 223 patients (2.5%) in the semaglutide group and in 262 patients (3.0%) in the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.71 to 1.01; P = 0.07). Because death from CV causes didn’t quite reach the required P value for hierarchical testing, superiority testing was not done on the rest of the other secondary end points.

However, if look at the graphs in Figure 1, it would seem that the other secondary end points did achieve their superiority. For example, the hazard ratio for the heart failure composite end point was 0.82 (95% CI, 0.71 to 0.96), and the hazard ratio for death from any cause was 0.81 (95% CI, 0.71 to 0.93). All the secondary end points showed a ~20% reduction. All their upper confidence interval were below 1.0 which gives us the confidence of superiority.

Other non-CV end points

Not surprisingly, the mean weight loss was -9.39 kg in the semaglutide arm vs -0.88 kg in the placebo arm (difference of -8.51kg between the groups). The mean HbA1c change from baseline was -31% in the semaglutide arm vs 0.01% in the placebo arm. Most interestingly, for participants whose HbA1c was ≥5.7% (prediabetes), 66% dropped their HbA1c to < 5.7% by week 52 and 65.7% by week 104 compared with 19.8% and 21.4% in the placebo arm.

This SELECT trial have demonstrated that in patients with obesity and established CVD without DM, once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4mg was associated with a 20% reduction in major adverse cardiac events during a mean exposure period of 33 months. Now these are patients who do not have diabetes. Most of these patients are already on statins, anti-platelet agents and beta blockers. Semaglutide 2.4mg have shown its benefits on top of these therapies. The cardioprotective effects of GLP-1 RA are not fully understood and likely multifactorial.

In patients with established CVD and who are already on “maximal” medical therapy, based on the SELECT trial results, should we be thinking about adding semaglutide 2.4mg to further reduce their CV events?

References:

1. Ma C, Avenell A, Bolland M, et al. Effects of weight loss interventions for adults who are obese on mortality, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2017; 359: j4849.

2. Bohula EA, Wiviott SD, McGuire DK, et al. Cardiovascular safety of lorcaserin in overweight or obese patients. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: 1107-17.

3. James WPT, Caterson ID, Coutinho W, et al. Effect of sibutramine on cardiovascular outcomes in overweight and obese subjects. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 905-17.

4. The Look AHEAD Research Group. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 145-54.

5. Nissen SE, Wolski KE, Prcela L, et al. Effect of naltrexone-bupropion on major adverse cardiovascular events in overweight and obese patients with cardiovascular risk factors: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2016; 315: 990-1004

6. Lincoff AM, Brown-Frandsen K, Colhoun HM, Deanfield J, Emerson SS, Esbjerg S, Hardt-Lindberg S, Hovingh GK, Kahn SE, Kushner RF, Lingvay I, Oral TK, Michelsen MM, Plutzky J, Tornøe CW, Ryan DH; SELECT Trial Investigators. Semaglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Obesity without Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2023 Nov 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2307563