12th November 2023, Conjoint Assoc. Prof Chee L Khoo

It is pretty standard for us to treat an infective exacerbation of COPD with antibiotics and a shot of oral corticosteroids, usually oral prednisolone for 5-7 days. Almost all of them seems to get better with that regimen. Or do they? We explored when to use and when not to use inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) in COPD in the September 2023 issue. Patients with COPD and low eosinophil counts were less likely to respond to ICS and were also more likely to get infections. Well, would that principle then apply to oral corticosteroids? Well, someone did a study on that question.

In patients with COPD, lower blood and sputum eosinophils are associated with greater presence of proteobacteria, notably Haemophilus, increased bacterial infections & pneumonia. These patients have a higher risk of pneumonia.

There is a continuous relationship between blood eosinophil counts and ICS effects. No and/or small effects are observed at lower eosinophil counts, with incrementally increasing effects observed at higher eosinophil counts. Data modelling indicates that ICS containing regimens have little or no effect at a blood eosinophil count < 100 cells/μL, therefore this threshold can be used to identify patients with a low likelihood of treatment benefit with ICS.

The studying acute exacerbations and response (STARR2) study was a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial conducted in 14 primary care practices in the UK. The authors explored whether the use of eosinophil count at the time of an exacerbation of COPD was effective at reducing prednisolone use without affecting adverse outcomes. They recruited adults (aged ≥40 years), who were current or former smokers (with at least a 10-pack per year smoking history) with a diagnosis of COPD, defined as a post-bronchodilator FEV1/forced vital capacity ratio of less than 0·7, previously recorded by the primary care physician and a history of at least one exacerbation in the previous 12 months requiring systemic corticosteroids with or without antibiotics.

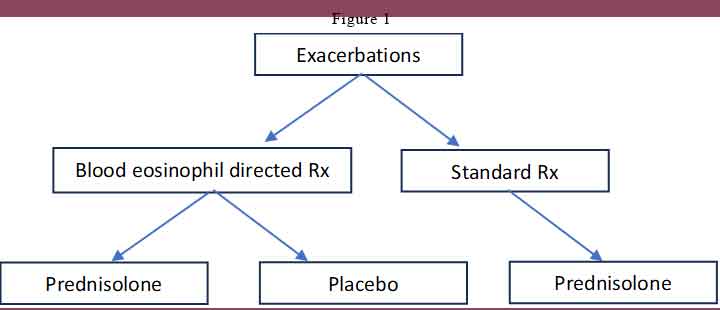

Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) to blood eosinophil-directed treatment (BET) or to standard care treatment (ST). Randomisation was stratified for the blood eosinophil count (<2%, 2 to <4%, ≥4%), percentage FEV1 at baseline (<50% or ≥50% predicted), and the number of exacerbations in the previous 12 months (<2 or ≥2 exacerbations).

At each visit, participants had post-bronchodilator spirometry and completed patient-reported questionnaires (Medical Research Council dyspnoea scale; visual analogue score [VAS]; COPD Assessment Test [CAT]; the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS]; and the EuroQol 5D). Participants also had a point-of-care measurement of blood eosinophils and C-reactive protein.

At the time of randomisation, if the point-of-care blood eosinophil count was high (≥2%), participants in the BET group received oral prednisolone 30 mg once daily, and if the blood eosinophil count was low (<2%), participants received matched placebo instead. Participants in the ST group received oral prednisolone 30 mg once daily irrespective of the point[1]of-care blood eosinophil count. See Figure 1.

The primary outcome they were looking for was the proportion of treatment failure—defined as exacerbations needing re-treatment, hospital admission, or death—at 30 days (and at 90 days as a separate endpoint). Retreatment was defined as the need for retreatment with systemic glucocorticoids with or without antibiotics.

Unfortunately, they had a problem with the randomisation software after commencement of the trial. Due to the serious errors in randomisation and the resultant reduction in power as a superiority trial, the trial was converted to show non-inferiority before data lock (Feb 22, 2022). No participants were unmasked from treatment allocation.

The Results

If you just read the conclusions in the extract which says “Blood eosinophil-directed prednisolone therapy at the time of an acute exacerbation of COPD is non-inferior to standard care and can be used to safely reduce systemic glucocorticoid use in clinical practice”, you could be forgiven to think that COPD exacerbation can be safely treated without oral glucocorticoids. But if you read the study in detail, you will come to a different conclusion.

76 participants were randomised to BET and ST arms each. 75% of participants were ex-smokers. 58% of participants were already on ICS. Participant characteristics at baseline were largely similar between the study groups although the participants randomly assigned to BET had more current smokers, more heart failure, and higher VAS symptoms of cough and breathlessness at baseline compared with participants allocated to ST. 20% of 93 participants treated with BET or ST had a eosinophil count of more than 0·3×10⁹ cells per L (300 cells per µL) at baseline.

Some patients and some exacerbations had to be excluded due to the randomisation errors. After the exclusions, 144 exacerbations in 93 patients were randomised – 73 to BET arm and 71 to ST arm. In the BET group, there were 48 (66%) exacerbations that received prednisolone compared with 71 (100%) exacerbations that received prednisolone in the ST group. Most of the exacerbations [65%] were in the high (≥2%) eosinophil category.

There were 19% treatment failure in the BET arm and 32% treatment failure in the ST arm. The hazard ratio was 0.71 but with p=0.200 it indicates non-inferiority (because of the loss of numbers from the randomisation error).

With regard to the secondary outcomes, at day 14 there was no significant difference in the improvement of post-bronchodilator FEV1, CAT, or VAS symptoms between the BET and ST groups. At 30 days, CAT did not return to baseline in the ST group and was significantly worse ( p=0·0060) than BET, indicating incomplete recovery.

If we delve into the details:

- At Day 30, there were more treatment failures amongst those with low eosinophil count compared with those with high eosinophil count (30% vs 23%)

- At Day 14, exacerbations in patients with high eosinophil count treated with prednisolone had better response in FEV1 compared with those with low eosinophil count treated with placebo.

- In patients with low eosinophil count, symptoms (as measured by CAT, FEV1, and VAS) returned to baseline after the exacerbations. They were not clinically or significantly different between patients with exacerbations with similar low eosinophil count whether treated with prednisolone or placebo. In other words, prednisolone had no effect if you have low eosinophil count.

- In fact, there were fewer treatment failures in exacerbations with low eosinophil count treated with placebo compared with exacerbations with low eosinophil count treated with prednisolone at day 30.

- On the other hand, for those patients with high eosinophil count, despite treatment with prednisolone, there was an incomplete resolution at day 30 of CAT, FEV1, and VAS (total, dyspnoea, and wheeze).

So, in summary, we can say that in patients with COPD and in exacerbation, if the eosinophil count were low, not using oral prednisone was not inferior to standard care of using oral prednisone. Thus, they were able to reduce unnecessary prednisone use in these patients. Further, it reminds us that with COPD exacerbation, whether we use prednisolone or not, lung function do not return to pre-exacerbation normal.

References:

Ramakrishnan S, Jeffers H, Langford-Wiley B, Davies J, Thulborn SJ, Mahdi M, A’Court C, Binnian I, Bright S, Cartwright S, Glover V, Law A, Fox R, Jones A, Davies C, Copping D, Russell RE, Bafadhel M. Blood eosinophil-guided oral prednisolone for COPD exacerbations in primary care in the UK (STARR2): a non-inferiority, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2023 Nov 1:S2213-2600(23)00298-9. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00298-9. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37924830.