25th November 2023, A/Prof Chee L Khoo

Cervical screening for cervical cancer for the prevention of cervical cancer has to be one of the most successful campaigns in primary care. For most, instead of having an intimate check every two years, doing it every 5 years is such a relief. For others, it is still having to endure an insertion of a vaginal speculum. Understandably, this aversion of speculum is keeping many people from having any sort of screening. What about self-collection? It seems to be put in the second-choice basket for both patients and doctors. Many doctors discourage self-collection as it is deemed to be less accurate. As a result, we are still missing many people who go on to develop cancer of the cervix. In other words, we are very successful only in those who turn up volunteering for a check up but still missing many who don’t turn up. It’s “hands up who is not here?”

Internationally, the annual number of new cases of cervical cancer has been projected to increase from 570 000 to 700,000 between 2018 and 2030, with the annual number of deaths projected to increase from 311 000 to 400,000. More than 85% of those affected are young, undereducated women who live in the world’s poorest countries. Many are also mothers of young children whose survival is subsequently truncated by the premature death of their mothers.

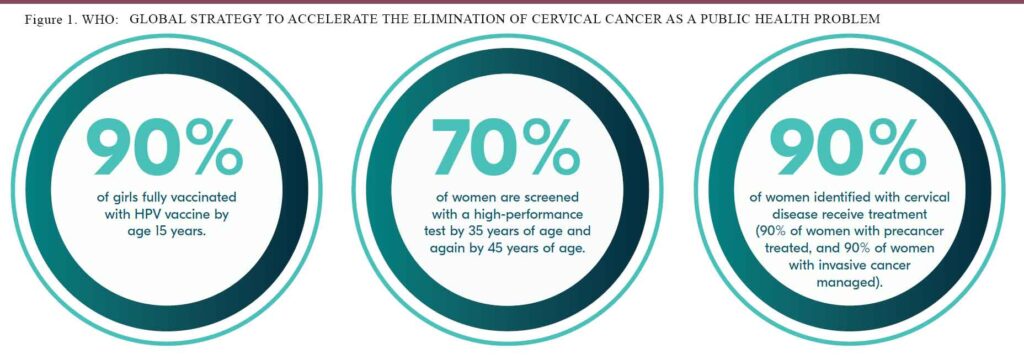

In November 2020, the World Health Organization officially launched the Global Strategy to Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer. The goal was to aim for threshold of 4 per 100 000 women-years for elimination as a public health problem. To achieve the following targets must be met by 2030:

- 90% of girls fully vaccinated with HPV vaccine by age 15 years.

- 70% of women are screened with a high-performance test by 35 years of age and again by 45 years of age

- 90% of women identified with cervical disease receive treatment (90% of women with precancer treated, and 90% of women with invasive cancer managed).

Australia has signed up to the strategy and developed the National Elimination Strategy and this was launched on 17th November 2023. We are aiming for 95% of eligible people will receive optimal treatment for pre cancer and cancer and we are hoping to achieve 90/70/95 before 2030 (see figure 1).

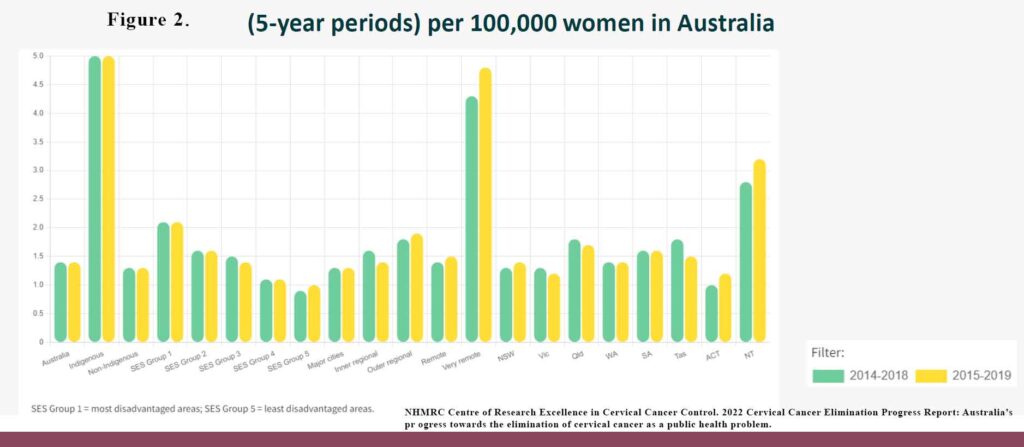

One of the facets of the strategy is reaching out to those at-risk groups that have low screening rates. Over 70% of cervical cancer occurs in women who are under screened. This inequity exists depending on who you are, where you live and your socio-economic status. The vision is to target these priority groups:

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- Culturally and linguistically diverse groups

- People who are LGBTQI+ and people who are intersex

- People with disability

- People living in rural and remote areas.

As you can see in Figure 2, the ATSI and remote women are very overrepresented in cervical cancer mortality in Australia.

To reach out to more under screened people, since July 2012, participants have the option of using:

There is a large body of evidence demonstrating a high level of acceptability of self-collection, particularly for those who are under-screened:

Patients prefer self-collection for many good reasons:

- Minimal embarrassment or shame

- Privacy

- No pain or discomfort

- Quick, easy and convenient

- Autonomy and control

- Empowerment

Self-collection is safe and reliable

Safety controls on HPV test ensure that samples taken incorrectly, or affected by contaminants are reported as ‘unsatisfactory’ rather than ‘negative’. Contaminants, such as blood, microbial infection or lubricant, may inhibit the PCR reaction and therefore the ability of an assay to detect HPV. The lab ensures that there is enough cellular material in the sample to be valid.

The commonly used device for self collection is the Copan FLOQswab (red top) flocked swab 552C or 552C.80 (see Figure 3). Depending on your provider, the swab is delivered either dry to the lab for processing or re-suspended in the ThinPrep vial and then delivered to the lab. You need to check with your lab.

In a meta-analysis comparing physician collected sample vs patient collected sample, the accuracy of HPV in the assays were almost identical (7). As physicians, we can be assured that a self-collection is still as accurate. We can also assure patients that self-collection is not inferior.

Who should not have self-collection?

Naturally, self-collection samples will not have cervical cells and cannot be used for cytology. If HPV is detected, then patient can be recalled so that cervical sample can be taken for informed management. Similarly, patients with symptoms such as unexplained vaginal bleeding (Post coital bleeding, inter menstrual bleeding, post-menopausal bleeding), unexplained, persistent or unusual vaginal discharge need more than self-collection. Self-collection cannot be used in patients following treatment for CIN2/3.

Patients should be encouraged to take a self-collected sample in the clinic , where possible, however there is flexibility in the guidelines allowing it to be taken in any setting the referring HCP believes is appropriate.

Self-collection is one of the best tools we have available to work towards the equitable elimination of cervical cancer in Australia. Let’s work together towards getting more people screened and not wait for “hands up who is not here”. There are many priority groups that are under screened and self-collection should be offered.

References:

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2021. National Cervical Screening Program monitoring report 2021. Cancer series 13 4. Cat. no. CAN 141. Canberra: AIHW.

- Creagh et al (2021) Self collection cervical screening in the renewed National Cervical Screening Program: a qualitative study, Med J Aust

- MacDonald et al (2021). Reaching under screened/never screened indigenous peoples with human papilloma virus self testing: A community based cluster randomised controlled trial, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Butler et al (2020). Indigenous Australian women’s experiences of participation in cervical screening, PloS one

- Saville et al (2018). SelfCollection for Under Screened Women in a National Cervical Screening Program: Pilot Study, Curr . Oncol

- Whop et al (2022). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s views of cervical screening by self-collection: a qualitative s tudy, Aust N Z J Public Health

- Arbyn M. et al. BMJ. 2018 Dec 5;363:k4823.doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4823