31st October 2025, A/Prof Chee L Khoo

The role of aspirin is well established in secondary prevention of cardiovascular events. However, it’s coming up to 10 years since international guidelines specifically recommend against aspirin in primary prevention of CV events (1-3). There have been a number of landmark studies looking at the risk and benefits of aspirin in primary prevention. Many of these studies demonstrate benefits of aspirin in primary prevention but a number of landmark studies have demonstrated the net harms of aspirin in these patients. We need to explore how we got here.

We know that aspirin has a net benefit in secondary prevention but prior to 2018, there was insufficient evidence to reliably inform whether daily, low-dose aspirin offered a potential benefit in older persons without atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD) events. In the ASPREE trial (2018), not only did aspirin not statistically improve mortality or reduce CVD events over a median 4.7 years, it actually increased risk of major haemorrhage and deaths from cancer (4). ASPREE was instrumental in the update in the guidelines in 2018 against routine aspirin initiation in older adults for primary prevention of atherosclerotic CVD events.

The ASPREE results were released about the same time as two other trials, ASCEND and ARRIVE. While the median age in the ASPREE trial participants was 74 years old, ASCEND recruited participants > 40years and the median age of the participants was 63 years old. None of the participants had known CVD (5). After a median of 7.4 years, there was a 12% reduction in serious vascular events but there was also a significant 29% increase in major bleeding events. Overall, all the cardiovascular benefits were counterbalanced by the increased in bleeding events.

ARRIVE recruited similar aged participants (median age 64 years old) but with moderate CV risks based on risk factors (6). After a median follow up of 5 years, there was no significant difference in the CV outcomes but there as a > 2x increase in bleeding events.

ASPREE, ASCEND and ARRIVE reported in 2018 and came at the back of an earlier AntiThrombotic Trialist (ATT) meta-analysis in 2009 which concluded that the benefits of aspirin in primary prevention needed to be balanced against the risk of bleeding (7). A later systematic review and meta-analysis in 2019 came to the same conclusion (8). Yet, even after the recommendations against routine use of aspirin in primary prevention in the guidelines, an estimated 23%–46% of older adults in the US population still regularly take low-dose aspirin for primary prevention. I suspect the numbers are similar in Australia.

ASPREE continue the study of the original patients in an extended follow-up study which reported two months ago (9). It is very useful to explore what they found after another 4.3 years post trial. Let’s recap to look at the original ASPREE trial. It was a large-scale placebo-controlled randomised trial of daily 100 mg enteric-coated aspirin conducted in 19,114 adults aged ≥70 years residing in Australia and the USA (≥ 65 years for US minorities) who had no prior cardiovascular events, dementia, or independence-limiting physical disability at trial enrolment. Recruitment started in 2010 and the median age of the participants at enrolment was 74 years old. The trial was terminated 6 months earlier on June 12, 2017 when it was evident that the benefits of reduction in the primary outcome was unlikely to be achieved.

Participants were not aware of the findings of the trial until another 15 months. Participants who were on trial medications (aspirin or placebo) were asked to return the medications while participants taking aspirin on recommendations of their treating doctors were asked to continue. They were all informed of the results when it was published in September 2018.

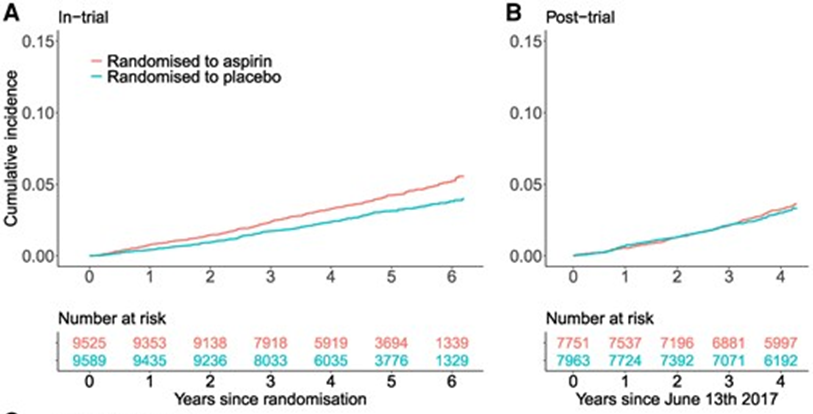

Participants were followed for a median of 4.3 years for MACE and major haemorrhage in the post-trial period. There were 18% higher rates of MACE and 25% higher risk of myocardial infarction in those randomised to aspirin compared with those randomised to placebo, whereas during the trial, these rates were lower in the aspirin group compared with placebo. The increased risk of MACE post-trial in those randomised to aspirin was not limited to the first year of post-trial follow-up.

What does all this mean?

Although the conclusion from the original ASPREE trial

published in 2018 says that there was no mortality or CVD benefits after 4.7

years overall, there was a trend towards benefits which means there was a

slight benefit but it was not statistically significant. In fact, there was a

11% reduction in MACE during the trial. In the post-trial extension study, the

group that was randomised to aspirin during the trial and now randomised to

placebo, there was actually an 11% higher risk of MACE post-trial in

individuals originally randomised to aspirin compared with placebo. In other

words, while there may be a slight benefit of aspirin during the trial, if you

stopped the aspirin afterwards, the risk of MACE is higher subsequently. In

addition, continued use of aspirin in this group over the subsequent follow up

also did not result in benefits either.

The authors suggested that perhaps, cessation of aspirin my lead to rebound phenomenon. This phenomenon is thought to arise from the recovery of platelet cyclooxygenase activity and synthesis of thromboxane after aspirin cessation, resulting in increased platelet aggregation. This result is consistent with a large Swedish cohort study, in which individuals who discontinued low-dose aspirin had a 37% higher risk of MACE than those who continued aspirin over an average 3-year follow-up (10). Further, aspirin cessation may lead to a pro-inflammatory state which can contribute to the destabilization of atherosclerotic plaques, making them more prone to rupture, potentially years later (11).

It was further suggested that perhaps, all aspirin does was delay rather than prevent events and when aspirin was stopped, plaque rupture continues. It is possible that aspirin, by causing intraplaque haemorrhage, might be associated with MACE some time later.

Risk of major haemorrhage

Over the entire period of the in-trial and post-trial follow-up, 24% higher rates of major haemorrhage were observed in those randomised to aspirin compared with placebo, and likewise upper gastrointestinal bleeding was 43% higher and bleeding at another site was 25% higher. During the post-trial period alone, there was no significant difference in rates of major haemorrhage between the randomised aspirin and placebo groups with a HR for overall major haemorrhage of 1.08. See Figure 1 below.

In summary, we have to think super carefully when considering aspirin for primary prevention of CVD. We need to have a very good reason to initiate aspirin in these patients especially, older patients as the bleeding risk overwhelmed the CV benefits. We also need to be weary when we stop the aspirin after they have been on aspirin for primary prevention.

References:

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, Buroker AB, Goldberger ZD, Hahn EJ, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 2019;140:e596–646

- Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, Carballo D, Koskinas KC, Bäck M, et al. 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur Heart J 2021;42:3227–337

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, Cabana M, Chelmow D, et al. Aspirin use to prevent cardiovascular disease: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 2022;327:1577–84.

- McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods RL, Lockery JE, Wolfe R, Reid CM, et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1519–28.

- ASCEND Study Collaborative Group; Bowman L, Mafham M, Wallendszus K, Stevens W, Buck G, et al. Effects of aspirin for primary prevention in persons with diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2018;379:1529–39

- Gaziano JM, Brotons C, Coppolecchia R, Cricelli C, Darius H, Gorelick PB, et al. Use of aspirin to reduce risk of initial vascular events in patients at moderate risk of cardiovascular disease (ARRIVE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2018;392:1036–46.

- Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration; Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, Emberson J, Godwin J, et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet 2009;373:1849–60

- Zheng SL, Roddick AJ. Association of aspirin use for primary prevention with cardiovascular events and bleeding events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2019;321:277–87

- Rory Wolfe, Jonathan C Broder, Zhen Zhou, et al, Aspirin, cardiovascular events, and major bleeding in older adults: extended follow-up of the ASPREE trial, European Heart Journal, 2025;, ehaf514,

- Sundstrom J, Hedberg J, Thuresson M, Aarskog P, Johannesen KM, Oldgren J. Low-dose aspirin discontinuation and risk of cardiovascular events: a Swedish nationwide, population-based cohort study. Circulation 2017;136:1183–92

- Stone PH, Libby P, Boden WE. Fundamental pathobiology of coronary atherosclerosis and clinical implications for chronic ischemic heart disease management—the plaque hypothesis: a narrative review. JAMA Cardiol 2023;8:192–201