28th October 2023, A/Prof Chee L Khoo

It’s all deja-vu again. In January, we discussed the name change from NAFLD to MAFLD. We also discussed how the metabolic dysfunction fatty liver disease (MAFLD) nomenclature and definition were not quite universally accepted internationally. Somehow, we knew that MAFLD was really a temporary placeholder. And indeed, it was and many international bodies have got together since then and put together a consensus nomenclature for metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease or MASLD (pronounced MASL-D). It’s most insightful to go through how the name came about and the reasons why. For a start, the number of listed authors spanned 6 pages. I am sure, many, many other contributors were not listed.

Why was there a need for name change?

If you look at the original non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) definitions that we have become used to, they were very reliant on excluding alcohol in the definition. We partly addressed the alcohol with MAFLD by allowing alcohol related fatty liver disease to be included in MAFLD because not uncommonly patients have both. But it was a little unclear in some patients how much of the steatosis was alcohol related and how much was dysmetabolism related and we need to sub-categorise this group.

We also learnt in our discussion in January when the name change went from NAFLD to MAFLD that a significant proportion of patients with steatosis were not “fat”. So, it was thought that using the term “fatty liver disease” was potentially stigmatising and further, may give some clinicians and patients a false sense of reassurance that the patient in front of them is safe because they were not fat or obese.

The process

Because there were disagreements with the earlier MAFLD nomenclature and definitions, three pan national liver associations were involved in a modified Delphi process to develop a group consensus using literature review and opinions from experts and patient advocates. There were multi-stakeholder effort under the auspices of the American Association for Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) and the European Association for Study of the Liver (EASL) in collaboration with the Asociación Latinoamericana para el Estudio del Hígado (ALEH) with engagement of academic professionals from around the world including hepatologists, gastroenterologists, paediatricians, endocrinologists, hepatopathologists and public health and obesity experts along with colleagues from industry, regulatory agencies and patient advocacy organisations to resolve these concerns and develop a consensus on a change in nomenclature and the diagnostic criteria for the condition.

A total of 236 panellists from 56 countries participated in four online surveys and two hybrid meetings. Consensus was defined a priori as a supermajority (67%) vote. An independent committee of experts external to the nomenclature process made the final recommendation on the acronym and its diagnostic criteria.

The issue of alcohol consumption

A supermajority felt that consumption of 30g-60g of alcohol daily in the setting of NAFLD alters the natural history of disease (95%) and may alter response to therapeutic interventions (90%). Furthermore, 90% felt that individuals with steatosis related to metabolic risk factors who consume more than minimal alcohol (30g-60g daily) represented an important group that should be considered in a different disease category and studied independently.

The Nomenclature process

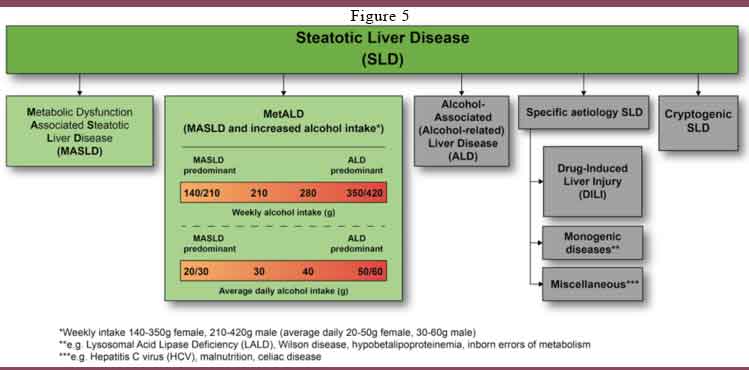

We won’t go into the voting process that led to the final nomenclature. First off, all fatty liver disease is now put under the umbrella term of Steatotic Liver Disease (SLD). This is generally a imaging (ultrasound) diagnosis and as you know, steatosis can be present without any abnormal liver function tests.

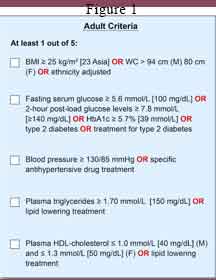

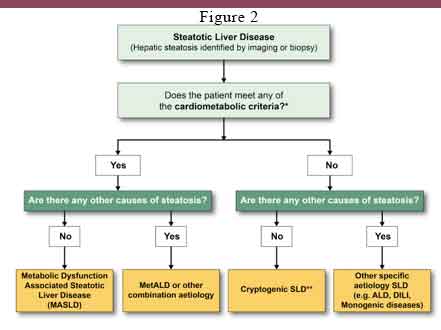

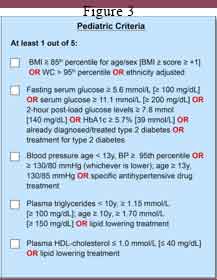

Under the umbrella term of SLD, if the patient has 1 out of 5 of elements of metabolic syndrome (see Figure 1), then the patient has MASLD unless there are other causes of steatosis such alcohol related SLD (see Figure 2).

If the patient does not have Metabolic Syndrome and there are no other causes of steatosis, then they fall under Cryptogenic SLD.

The paediatric criteria for metabolic syndrome is a little more stringent. (See Figure 3)

What about the paediatric population?

There was a high degree of consensus among the paediatric panellists when considering statements/questions pertaining to the paediatric population. Only paediatricians answered the paediatrics specific questions, and the main themes addressed the role of stigma, use of the term ‘metabolic’ and the histological definition of the disease. In children and adolescents, 60% felt that use of the term ‘non-alcoholic’ was stigmatising for parents and/or paediatric patients, with 55% finding this to be the case with the term ‘fatty’.

When asked if the current definition, of NASH is less useful in children and adolescents due to a lower frequency of hepatocyte ballooning, 95% agreed that a reassessment of the definitions of steatohepatitis in the paediatric setting would be beneficial. In considering incorporation of the term ‘metabolic’ into the nomenclature, 90% estimated that this term may be confusing in the paediatric context since inborn errors of metabolism are referred to as ‘metabolic liver disease’.

What about alcohol?

As we know, the original NAFLD excluded patients with steatosis who consume “excessive” alcohol but we know patients can have metabolic dysfunction associated fatty liver disease as well alcohol related fatty liver disease. That was the how MAFLD was formed to be inclusive and not exclusive of alcohol.

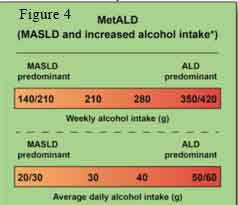

In the new nomenclature, there is a subcategory of MASLD where is a continuum of contribution of MASLD and Alcohol Liver Disease (ALD). In this subcategory, MetALD, limits are set on the weekly intake of alcohol. Where weekly alcohol intake is < 140g for women and <210g for men or daily alcohol intake of 20g for women and 30g for men, according to current literature, the steatosis is thought to be mainly from metabolic dysfunction. At the other end of the spectrum of alcohol intake, where weekly alcohol intake is >350g/420g (women/men) or daily alcohol intake >50g/60g (women/men), much of the steatosis is likely to be from excessive alcohol (see Figure 4).

Currently, validated objective tools are not available to determine the relative contribution of MASLD and ALD in patients with MetALD and hence we rely on self-reported alcohol intake which can be inaccurate. he safe alcohol amount due to individual genetic differences and the relative contributions of metabolic dysfunction and alcohol to MetALD disease progression remain uncertain.

Of course, the is a subcategory of pure alcohol related liver disease where is steatosis in the absence of metabolic syndrome elements. This is now termed ALD.

NASH is now MASH

As mentioned, the diagnosis of steatosis is primarily by imaging (sometimes from biopsies) with or without abnormal liver function tests (hepatitis). The old term Non-Alcoholic SteatoHepatitis (NASH) refers to steatosis with hepatic inflammation which is associated with increasing prevalence of fibrosis and cirrhosis. This subgroup is a progression from the more benign MASLD to the more severe disease of Metabolic Dysfunction related SteatoHepatitis (MASH).

The Others

Of course, there are other causes of steatosis apart from alcohol and metabolic syndrome including drug induced liver injury, Wilson’s disease, inborn errors of metabolism, hepatitis B and C, malnutrition and coeliac disease. These are listed under specific aetiology SLD. Lastly, if no cause is found, then they are called cryptogenic SLD.

The Final Nomenclature (see Figure 5).

This will not be the final word on steatosis. It is hoped that the new nomenclature will enhance disease awareness, since the alignment of the diagnostic criteria for MASLD with widely recognized phenotypic traits in diabetes and cardiovascular medicine will make it easier for the larger community of healthcare providers to identify individuals with this condition. There is more work to be done to increase disease awareness, reduce stigma and accelerate drug and biomarker development to benefit patients with MASLD and MetALD.

Reference:

Rinella ME, Lazarus JV, Ratziu V, Francque SM, Sanyal AJ, Kanwal F, et al. A multi-society Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Hepatology. 2023 Jun 24. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000520.