13th June 2020, Dr Chee L Khoo

We are not talking about whether front line workers should wear a mask or not. We are talking about masks for the general public. Even as medical practitioners, we are confused. How does the average member of the public decide whether to wear masks or not? There are so many different opinions from numerous different quarters. Sure, if you have Covid-19, wearing a mask will prevent you from sharing the virus. What if you are healthy? Should you wear a face mask? What does the evidence tell us? Is there even evidence to guide us?

What does the evidence say?

Yes, we were told that if you are well, wearing a non-medical mask doesn’t quite protect you from catching Covid-19. We were told that the evidence is there. When you hear from most (if not all) experts that non-medical face masks do not protect healthy individuals from catching the infection, you assume that the evidence must be overwhelming and consistent. Is it?

Transmission

The virus is primarily transmitted between people via respiratory droplets and contact routes. Droplet transmission occurs when a person is in close contact (within 1 metre) with an infected person and exposure to potentially infective respiratory droplets occurs, for example, through coughing, sneezing or very close personal contact resulting in the inoculation of entry portals such as the mouth, nose or conjunctivae. Transmission may also occur through fomites (surfaces) in the immediate environment around the infected person.

The presence of viral RNA is not the same as replication- and infection-competent (viable) virus that could be transmissible and capable of sufficient inoculum to initiate invasive infection. Viral RNA can be detected in samples weeks after the onset of illness but viable virus was not found after day 8 post onset of symptoms (1, 2) for mild patients, though this may be longer for severely ill patients.

The incubation period for Covid-19 is on average 5-6 days but can be as long as 14 days. Transmission may occur before symptoms begin to show (pre-symptomatic stage). Of course, there are patients who do not have any symptoms and their infectivity is unclear (asymptomatic carriers).

Transmissibility of the virus depends on the amount of viable virus being shed by a person, whether or not they are coughing and expelling more droplets, the type of contact they have with others and what preventative measures are in place. Studies that investigate transmission should be interpreted bearing in mind the context in which they occurred.

The evidence on the use of face masks

Because the Covid-19 pandemic is such a rapidly moving front, knowledge of transmission is accumulating every day. We have studies pre-Covid-19 pandemic involving influenza and other coronaviruses to provide us with evidence whether the wearing of masks by infected individuals can prevent transmission to healthy individuals and the surrounding environment (3,4).

In a cluster-randomised controlled trial conducted in France during the 2008-2009 influenza season, patients who were confirmed by the rapid influenza test (the index cases) were instructed to wear a mask within 48 hours of the onset of flu symptoms for 7 days (5). Households with 3-8 members were recruited but only the index cases wore masks. The primary outcome was the proportion of household contacts who developed influenza like illness (ILI). They found that facial masks in the index case alone were not more effective in preventing transmission to other household contacts. The trial was terminated prematurely due to insufficient number of influenza sufferers that year. The low numbers in the study lack statistical power to make any conclusions on the effectiveness of face masks.

A similar study from Hong Kong explored the secondary infection in household contacts of an index case (6). Index cases and all household contacts either wore face mask alone, practised strict hand hygiene without masks or neither mask nor hand hygiene. There was no difference in secondary attack rates between the groups. However, adherence to interventions were variable. Many in the control group wore masks and practiced strict hand hygiene measures in various degrees. Studies from Bangkok also failed to show benefit of face masks and hand hygiene but the control group was contaminated by a national education campaign which increased face mask use and hand washing during the trial (7).

There is limited evidence that wearing a medical mask by healthy individuals in households who share a house with a sick person or among attendees of mass gatherings may be beneficial as a measure preventing transmission (8, 9-14). In a trial conducted in Berlin during the 2009/10 and 2010/2011 influenza season, 84 households were randomised to either wearing face masks and intensive hand hygiene, face masks only or neither of the two (12). Face masks with or without intensive hand hygiene resulted in significant reduction in influenza transmission rates compared with the control group (neither mask nor hand hygiene).

In a systematic review involving 17 eligible studies, 6 out of 8 trials found no significant differences between intervention (medical masks +/- hand hygiene) and control groups. Eight of nine retrospective observational studies found that mask and⁄or respirator use was independently associated with a reduced risk of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).

A recent meta-analysis of these observational studies showed that neither disposable surgical masks or reusable 12–16-layer cotton masks were associated with protection of healthy individuals within households and among contacts of cases (8).

Now, those were studies with influenza virus. At present, there is no direct evidence from studies on COVID-19 and in healthy people in the community on the effectiveness of universal masking of healthy people in the community to prevent infection with respiratory viruses, including COVID-19.

Thus, the evidence of benefit (or lack of) is still conflicting. While the evidence supporting the use of face mask +/- hand hygiene is limited, the evidence to the contrary is not exactly robust either. In my opinion, the evidence is conflicting at best.

Which mask?

While medical masks are certified according to international or national standards to ensure they offer predictable product performance when used by health workers, according to the risk and type of procedure performed in a health care setting, it’s not the case with non-medical masks. Non-medical masks may be made of different combinations of fabrics, layering sequences and available in diverse shapes. Few of these combinations have been systematically evaluated and there is no single design, choice of material, layering or shape among the non-medical masks that are available. The unlimited combination of fabrics and materials results in variable filtration and breathability.

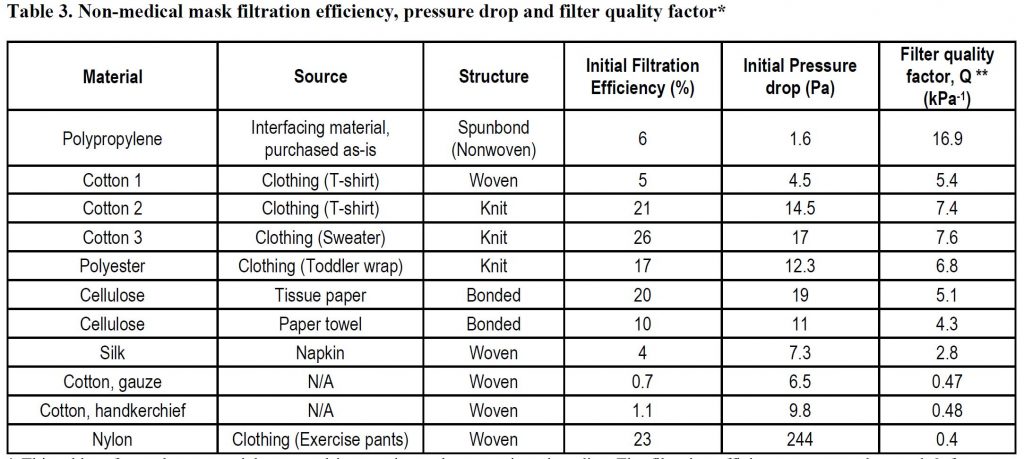

Filtration efficiency is dependent on the tightness of the weave, fibre or thread diameter, and, in the case of non-woven materials, the manufacturing process. The higher the filtration efficiency the more of a barrier provided by the fabric. The filter quality factor known as “Q” is a commonly used filtration quality factor; it is a function of filtration efficiency (filtration) and breathability, with higher values indicating better overall efficiency. According to expert consensus three (3) is the minimum Q factor recommended. See Table below.

Breathability is the difference in pressure across the mask and is reported in millibars (mbar) or Pascals (Pa) or, for an area of mask, over a square cm (mbar/cm2 or Pa/cm2). For non-medical masks, an acceptable pressure difference, over the whole mask, should be below 100 Pa.(73).

A minimum of three layers is required for non-medical masks, depending on the fabric used. The innermost layer of the mask is in contact with the wearer’s face. The outermost layer is exposed to the environment. The ideal combination of material for non-medical masks should include three layers as follows: 1) an innermost layer of a hydrophilic material (e.g. cotton or cotton blends); 2), an outermost layer made of hydrophobic material (e.g., polypropylene, polyester, or their blends) which may limit external contamination from penetration through to the wearer’s nose and mouth; 3) a middle hydrophobic layer of synthetic non-woven material such as polyproplylene or a cotton layer which may enhance filtration or retain droplets.

Users of face masks should perform hand hygiene before putting on the mask. Face masks need to cover the mouth and nose and adjust to the nose bridge. They need to be tied securely to minimize any gaps between the face and the mask. Users should avoid touching the mask while wearing it. Masks need to be removed using the appropriate technique: untie from the back and the front of the mask should not be touched.

Masks should be changed if wet or visibly soiled. Remove the mask without touching the front of the mask. Do not touch the eyes or mouth after mask removal. Either discard the mask or place it in a sealable bag where it is kept until it can be washed and cleaned. Perform hand hygiene immediately afterwards. Non-medical masks should be washed frequently and handled carefully, so as not to contaminate other items.

The use of medical masks by healthy individuals in the community may divert this critical resource from the health workers and others who need them the most. Medical masks should be reserved for health workers and at-risk individuals when indicated.

Here are two of many websites you can go to for making your own masks:

www.craftpassion.com/face-mask-sewing-pattern

https://happydiyhome.com/diy-face-mask/

Benefits of masks in healthy people

The use of masks by healthy people in the community reduced the potential transmission from an infected person who may either be asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic. If more healthy individuals wear face masks, it may reduce the stigma of healthy individuals wearing face masks. It also empowers people as they can play a role in contributing to spreading the virus.

Summary

So, should the healthy public wear face masks in Australia? Face masks made from the appropriate material, worn and don correctly and used together with hand hygiene probably does confer some benefit in reducing the risk of catching Covid-19 infection. Whether one should wear a face mask or not depends on what the risk of catching the infection in the general community (which depends on the prevailing community infection rates) and on whether one can social distance or not.

References:

- Symptom-Based Strategy to Discontinue Isolation for Persons with COVID-19. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; (https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/strategy-discontinue-isolation.html, accessed 4 June 2020).

- 2.Wolfel R, Corman VM, Guggemos W, Seilmaier M, Zange S, Muller MA, et al. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581(7809):465-9.

- Canini L, Andreoletti L, Ferrari P, D’Angelo R, Blanchon T, Lemaitre M, et al. Surgical mask to prevent influenza transmission in households: a cluster randomized trial. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e13998.

- MacIntyre CR, Zhang Y, Chughtai AA, Seale H, Zhang D, Chu Y, et al. Cluster randomised controlled trial to examine medical mask use as source control for people with respiratory illness. BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e012330.

- Canini L, Andre´oletti L, Ferrari P, D’Angelo R, Blanchon T, et al. (2010) Surgical Mask to Prevent Influenza Transmission in Households: A Cluster Randomized Trial. PLoS ONE 5(11): e13998. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013998

- Cowling BJ, Fung ROP, Cheng CKY, Fang VJ, Chan KH, et al. (2008) Preliminary Findings of a Randomized Trial of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions to Prevent Influenza Transmission in Households. PLoS ONE 3(5): e2101. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002101

- Simmerman et al. (2011) Findings from a household randomized controlled trial of hand washing and face masks to reduce influenza transmission in Bangkok, Thailand. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 5(4), 256–267.

- Jefferson, T., Jones, M., Al Ansari, L.A., Bawazeer, G., Beller, E., Clark, et al., 2020. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses. Part 1 – Face masks, eye protection and person distancing: systematic review and meta-analysis. MedRxiv.

- Cowling BJ, Chan KH, Fang VJ, Cheng CK, Fung RO, Wai W, et al. Facemasks and hand hygiene to prevent influenza transmission in households: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(7):437-46.

- Barasheed O, Alfelali M, Mushta S, Bokhary H, Alshehri J, Attar AA, et al. Uptake and effectiveness of facemask against respiratory infections at mass gatherings: a systematic review. Int J Infect Dis. 2016;47:105-11.

- Lau JT, Tsui H, Lau M, Yang X. SARS transmission, risk factors, and prevention in Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(4):587-92.

- Suess T, Remschmidt C, Schink SB, Schweiger B, Nitsche A, Schroeder K, et al. The role of facemasks and hand hygiene in the prevention of influenza transmission in households: results from a cluster randomised trial; Berlin, Germany, 2009-2011. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:26.

- Wu J, Xu F, Zhou W, Feikin DR, Lin CY, He X, et al. Risk factors for SARS among persons without known contact with SARS patients, Beijing, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(2):210-6.

- Barasheed O, Almasri N, Badahdah AM, Heron L, Taylor J, McPhee K, et al. Pilot Randomised Controlled Trial to Test Effectiveness of Facemasks in Preventing Influenza-like Illness Transmission among Australian Hajj Pilgrims in 2011. Infect Disord Drug Targets. 2014;14(2):110-6.

- bin-Reza et al. The use of masks and respirators to prevent transmission of influenza: a systematic review of the scientific evidence. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses 6(4), 257–267.

- https://www.who.int/publications-detail/global-surveillance-for-covid-19-caused-by-human-infection-with-covid-19-virus-interim-guidance