7th August 2021, Dr Chee L Khoo

It is always difficult for pregnant women to decide whether to have the Covid-19 vaccine during pregnancy. Understandably, they are concerned about the safety of the vaccine administered during pregnancy. When the pandemic started last year, there were some studies which suggest that Covid-19 during pregnancy is associated with “significantly” poor maternal and offspring outcomes. We need better data to have meaningful discussions with the pregnant women and their partners comparing the potential risks of vaccinating versus risks of not vaccinating during pregnancy. We now have data from a large clinical trial which assess the association between COVID-19 and maternal and neonatal outcomes in pregnant women with COVID-19 compared with pregnant women without COVID-19. The results shocked me.

The study was a prospective, longitudinal, observational study (INTERCOVID), involving 43 hospitals in 18 countries. From March 2020 to November 2020, 706 women with Covid-19 infection confirmed almost exclusively from PCR swabs were enrolled into the study. 1424 pregnant women without Covid-19 diagnosis were simultaneously enrolled for comparison of the pregnancy outcomes.

Both groups had similar demographic characteristics although more women who tested positive for Covid-19 were overweight early in pregnancy compared with women who did not have Covid-19 (48.6% vs 40.2%). Women who were diagnosed with Covid-19 also had higher rate of recreational drug use but lower rate of smoking during the index pregnancy, higher rates of previous preterm birth, stillbirth, neonatal death, and pre-existing medical conditions.

Outcomes

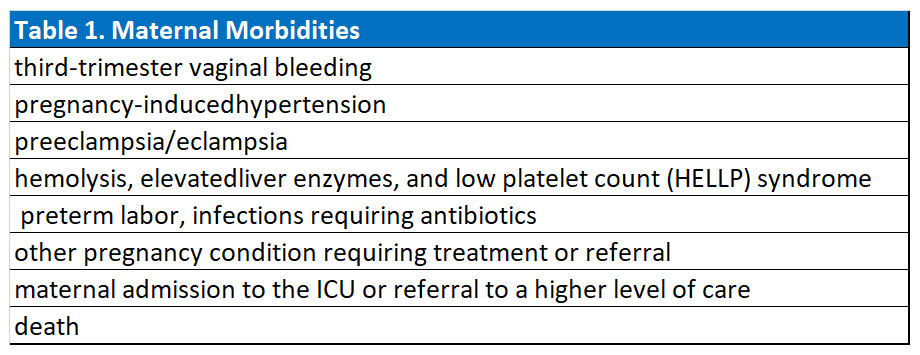

Maternal

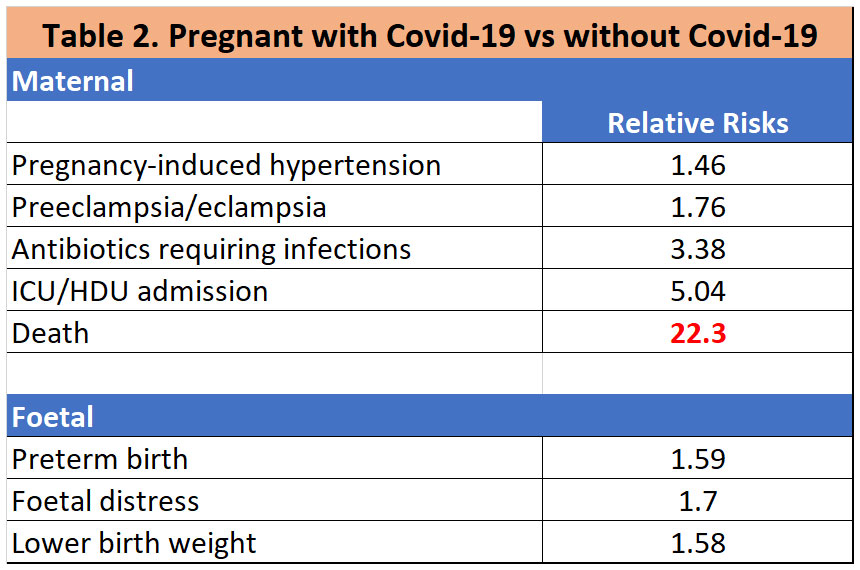

The primary outcomes were both maternal as well as foetal mortality and morbidity (see Table 1). Overall, not unexpectedly, maternal morbidity and mortality were significantly higher in women who tested positive for Covid-19 during pregnancy. 11 women (1.6%) with COVID-19 diagnosis died (maternal mortality ratio, 159/10000 births) (see Table 2). Of these, 4 had severe preeclampsia (1 superimposed on chronic hypertension and 1 associated with cardiomyopathy); 3 of these 4 women had respiratory failure that required mechanical ventilation and the fourth woman died of a pulmonary embolism. In comparison, in women without COVID-19 diagnosis, there was 1 death due to pre-existing liver malignant neoplasm and cirrhosis. Thus, women with COVID-19 diagnosis were 22 times more likely to die.

The presence of any symptoms increased the association with adverse outcomes. The presence of fever and shortness of breath, separately or in combination with any symptom cluster, was markedly associated with a risk of adverse outcomes in mother and child. Having shortness of breath, chest pain, and cough with fever was associated with a substantial increase in the risk for severe maternal and neonatal conditions and preterm birth.

Among those with no pre-pregnancy morbidities and those without overweight at their first antenatal visit, women with COVID-19 diagnosis were still at increased risk of these complications compared with women without COVID-19 diagnosis. However, for maternal outcomes, those women with COVID-19 diagnosis with pre-pregnancy morbidities had the highest risk in the index pregnancy, suggesting that past morbidities modify the effect ofCOVID-19 exposure, especially for preeclampsia/eclampsia (RR 3.29). Further, women who had overweight at the first antenatal visit and subsequently were diagnosed with COVID-19 had the highest risk for the maternal morbidity and mortality index (RR, 1.81), preeclampsia/eclampsia (RR, 2.62), suggesting that overweight status modifies the effect of COVID-19 exposure.

Overall, 41% of women with COVID-19 diagnosis were asymptomatic, a subgroup with a low risk of complications. Reassuringly, we also found that asymptomatic women with COVID-19 diagnosis had similar outcomes to women without COVID-19 diagnosis, except for preeclampsia.

Foetal

416 neonates (57.1% of the total) born to women who tested positive for Covid-19 were tested for Covid-19. Of these, 12.9% tested positive. Reassuringly, as SARS-CoV-2 has not been isolated from breast milk,35 breastfeeding was not associated with any increase in the rate of test positive neonates. The caesarean delivery rate was 72.2% in women who tested positive with test positive neonates compared with 47.9% in women who tested positive with test negative neonates and 39.4% in women who tested negative.

Even for test negative neonates of women with Covid-19, the risks for the serious neonate and perinatal morbidity and mortality and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) stay ≥ 7 days were higher compared with neonates of women without Covid-19. Expectedly, test positive neonates have even higher risks for SNMI and NICU stay ≥ 7 days.

Thus, it is clear that women are at significantly higher risk of mortality and morbidity if they contract Covid-19 while pregnant. In particular, they have 22X higher risk of death. In addition, neonates born to women who had covid-19 infection have a significantly higher perinatal mortality and morbidity.

Vaccination for women who are pregnant

Pregnant women are a priority group for COVID-19 vaccination and should be routinely offered Pfizer Comirnaty vaccine at any stage of pregnancy. Women who are trying to become pregnant do not need to delay vaccination or avoid becoming pregnant after vaccination. Real-world evidence has shown that Pfizer Comirnaty vaccine is safe for pregnant women and breastfeeding women. Here is the official guide from health department.

References:

Villar J, Ariff S, Gunier RB, Thiruvengadam R, et al. Maternal and Neonatal Morbidity and Mortality Among Pregnant Women With and Without COVID-19 Infection: The INTERCOVID Multinational Cohort Study. JAMA Pediatr. 2021 Aug 1;175(8):817-826. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1050. PMID: 33885740; PMCID: PMC8063132.