4th January 2023, Dr Chee L Khoo

The most recent US Prevention Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations pour cold water onto its use in primary prevention of CVD in April 2022 (1). We explored the details and rationale behind that turnaround recently. The recommendation for use of aspirin for prevention of colorectal cancer is lumped in together with the recommendation for CVD prevention. So, when aspirin for primary prevention of CVD was removed in April 2022, curiously, the recommendation for use in the prevention of colorectal cancer (CRC) was also removed at the same time. That has caused some disquiet amongst the colorectal experts. We explore the evidence for and against the use of aspirin for the prevention of CRC.

The biochemical role of aspirin in CRC prevention

Aspirin as chemoprophylaxis to prevent CRC? How does it even work? Before we venture into the biochemical basis of aspirin in CRC prevention, we need to look what we know about tumorigenesis – factors that promote cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion.

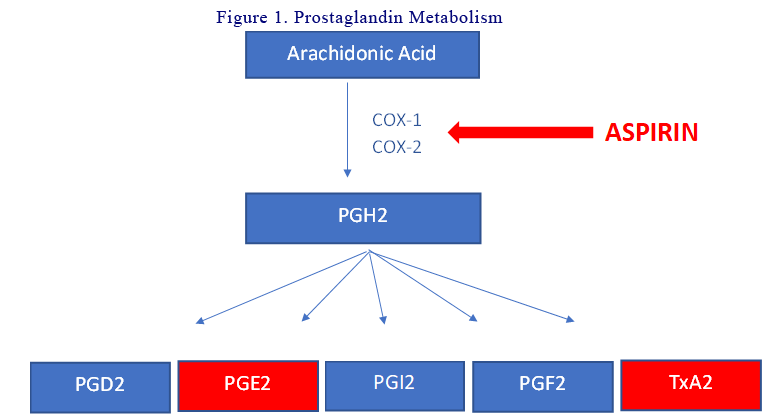

Prostaglandins Metabolism

The prostaglandins (PGs) are a group of physiologically active lipid compounds called eicosanoids having diverse hormone-like effects. They are derived from arachidonic acid. PGs are produced following the sequential oxygenation of arachidonic acid by cyclooxygenases (COX-1 and COX-2) and further by terminal prostaglandin synthases into different PGs. Aspirin inhibit COX-1 at low doses and COX-2 at high doses. For CRC tumorigenesis, PGE2 is the most important (see below). See Figure 1.

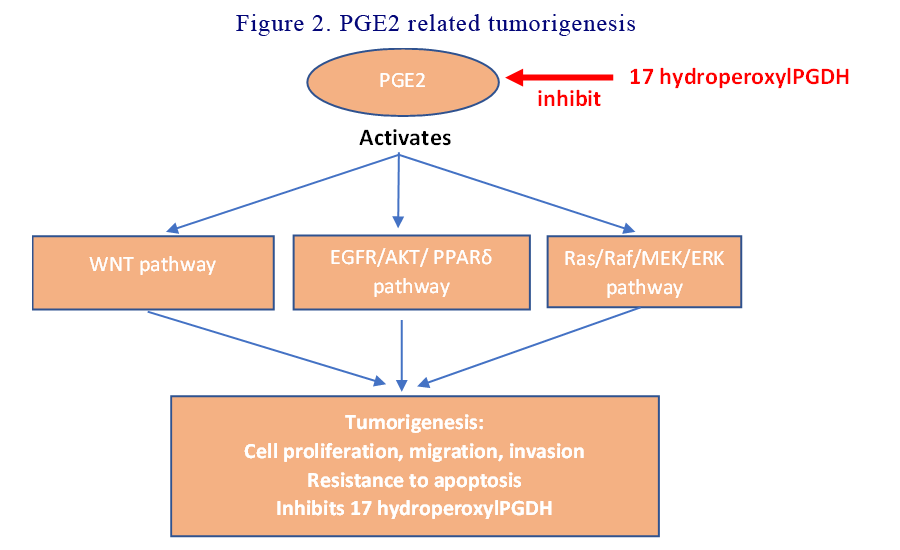

PGE2 related tumorigenesis

PGE2 acts directly on tumour epithelial cells by stimulating cellular proliferation and survival, as well as promoting migration and invasion of CRC cells. PGE2 induces cytoskeletal reorganisation that changes cellular shape and facilitates motility of CRC cells. PGE2 accomplishes all that by activating the WNT signalling, EGFR/AKT/PPARδ and Ras/MAP Kinase pathways. Aspirin directly inhibits PGE2 and modulate its tumorigenesis. See Figure 2.

PGE2 independent tumorigenesis

In addition to the PGE2 related tumorigenesis, there are other pathways which, when activated, favours the development of tumours. The NFkB, AMPK/mTOR and the apoptosis pathways inhibit apoptosis and autophagy which are key processes used by the body to get rid of misbehaving cells. Lipopolysaccharides from Gram-negative intestinal bacteria also activate some of these pathways. These pathways are blocked by aspirin.

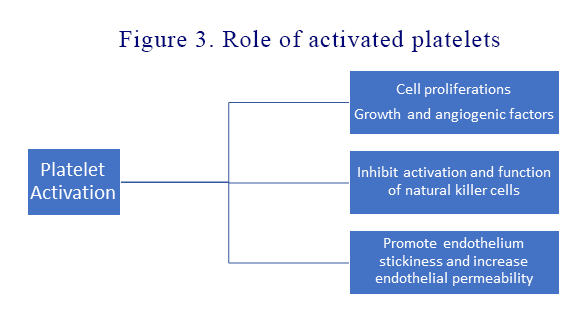

Activated platelet related tumorigenesis

Activated platelets play important roles in the multiple stages of colorectal carcinogenesis: 1) Activated platelets promote cell proliferation, stimulate angiogenesis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of tumour cells resulting in tumour cells becoming more invasive and intravasate in blood vessels 2) Activated platelets promote tumour cell survival in blood circulation by protecting them from natural killer (NK) cells. Secretion of TGF-β by activated platelets inhibits both the activation and function of NK cells 3) Activated platelets make extravasation and metastatic spread possible by promoting interactions between tumour cells and the vascular endothelium. This makes the endothelium both stickier and more permeable for cancer cells. By inhibiting platelet activation, aspirin has an anti-tumour effect. See Figure 3.

In order for aspirin to inhibit COX-2, it needs to be taken at high doses several times a day as platelets can re-synthesise COX-2 de novo. Thus, much of the inhibition of platelets occur due to inhibition of COX-1 which only require low dose aspirin.

Chronic inflammation related tumorigenesis

Chronic inflammation is an important hallmark of CRC since it contributes to its initiation as well as its progression. Neutrophils and fibroblasts produce inflammatory cytokines like TNFα, interleukin 1 and interleukin 6 into the tumour microenvironment. PGE2 production is increased by these cytokines as well as by COX-2 produced by the neutrophils and fibroblasts. PGE2 also activates neutrophils and fibroblasts causing more COX-2 production, feeding a positive feedback loop.

Aspirin in chemoprevention

Does aspirin chemoprevention work in real life? To answer the question, we need to look at studies aiming at preventing colorectal adenomas, CRC in normal individuals, CRC in individuals at high risk of CRC as well as treating CRC post diagnosis.

Aspirin for prevention of recurrent adenomas

Most CRCs develop from adenomas and it would make sense to target adenoma formation and recurrence before they become malignant. Many studies including several well-designed RCTs, shows that aspirin reduces colorectal adenoma recurrence rate and decreases the rate of advanced adenoma recurrence, the number of recurrent adenomas and delays the time to adenoma recurrence (2-5). A recent meta-analysis found a 20% reduction in risk in low-dose aspirin users (80 to 160 mg per day) compared to control patients (6).

Two recent RCTs (including one by Pomergaard et al) found no effect of aspirin on colorectal adenoma recurrence (7,8). Another RCT showed that aspirin reduced colorectal adenoma recurrence after 1 y but not after 4 y of follow-up (0). Ishikawa et al (6) found that daily low-dose aspirin that reduced colorectal adenoma recurrence worked primarily in non-smoking patients but was useless in patients who smoked. Perhaps, this could explain the negative results in Pomergaard’s study as there was a high proportion of smokers in the cohort.

Aspirin for CRC prevention

There have been numerous studies which has demonstrated aspirin as effective in reducing development of CRC. Long-term (up to 20 years) follow-up of cardiovascular trials have demonstrated, in post hoc analyses, that patients randomised to daily low-dose aspirin (75–300 mg) have a reduced risk of CRC incidence and mortality after a delay of several years.

A Danish retrospective case-control study showed a 37% reduction of CRC incidence in patients who were treated with daily low-dose aspirin for more than 5 y (10). A UK study found a 34% decrease in the risk of developing CRC in patients with daily low-dose aspirin. A meta-analysis of five RCTs showed a 24% decrease in the risk for developing CRC (11). This risk was especially reduced for proximal colon cancers. Daily low-dose aspirin also showed a 40% reduction for the risk of CRC mortality (12).

The ASPREE trial poured cold water onto the benefits of aspirin, though. The ASPREE trial was conducted to assess the impact of low-dose aspirin on disability-free survival among older adults who did not have cardiovascular disease, dementia or disability (13). When they looked at CRC mortality in a secondary analysis, they found that aspirin use was associated with a 31% higher risk for cancer-related mortality and colorectal cancer related mortality. The main criticisms of ASPREE were that the trials were relatively of short duration (mean 4.7 years) and the cohort were all >70 years old (mean 74 years). Any benefit that may have shown up with reducing CRC were easily negated by the significant morbidity and mortality of bleeding (minor or major).

Two large RCTs, the Physicians’ Health Study and the Women’s Health Study (WHS) also failed to demonstrate a protective effect of low-dose aspirin on CRC development in men and women, respectively (14,15). However, the extended follow-up (18 y after randomisation) of the WHS showed a significant 20% decreased incidence of CRC with aspirin.

It would seem from the myriad of studies that low dose aspirin reduces long term CRC risks if taken for more than 10 years and initiated at a younger age (50-59 years old).

Aspirin in CRC prevention in individuals at high risk of CRC

Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) and Lynch Syndrome are considered to have a very high risk for developing CRC. The Colorectal Adenoma/Carcinoma Prevention Programme 1 (CAPP1) study compared 600 mg aspirin treatment to placebo in patients with FAP aged 10 to 21 but did not find a significant difference in colorectal polyp burden (16). A 10 year follow-up of patients with Lynch syndrome on 600mg aspirin did find a 35% reduction in CRC.

Aspirin to treat CRC

Aspirin has been shown to reduce the progression of CRC after diagnosis (11). A retrospective study reported that long-term use of 100 mg aspirin in combination with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy increased the rate of downstaging and the pathological response rate in patients with rectal cancer (17). Further, a meta-analysis of 5 major studies comparing aspirin versus placebo in cardiovascular disease prevention showed that patients who develop adenocarcinoma are less likely to experience metastatic progression if they are treated with aspirin (18).

Our data on whether aspirin reduce the incidence of CRC or not is incomplete. We have many studies looking at CRC incidence and mortality as a secondary outcome on the back of CV outcome trials. The duration the patients were on aspirin for and the age of the cohort in those trials were not comparable in the numerous trials. I am not sure that it means aspirin has no benefit in reducing the risks of CRC but we need to weigh up the risks of bleeding in older patients. It also means that for aspirin to be beneficial, it needs a longer period of time and needs to be initiated when the patient is relatively younger. The debate continues.

References:

- https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/aspirin-to-prevent-cardiovascular-disease-preventive-medication. Accessed 29th December 2022.

- Sandler RS, Halabi S, Baron JA, et al. A randomized trial of aspirin to prevent colorectal adenomas in patients with previous colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(10):883–890. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021633.

- Baron JA, Cole BF, Sandler RS, et al. A randomized trial of aspirin to prevent colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(10):891–899. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa021735.

- Logan RFA, Grainge MJ, Shepherd VC, et al. ukCAP Trial Group. Aspirin and folic acid for the prevention of recurrent colorectal adenomas. Gastroenterology. 2008;134 (1):29–38. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.10.014

- Ishikawa H, Mutoh M, Suzuki S, et al. The preventive effects of low-dose enteric-coated aspirin tablets on the development of colorectal tumours in Asian patients: a randomised trial. Gut. 2014;63(11):1755–1759. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305827

- Veettil SK, Lim KG, Ching SM, Effects of aspirin and non-aspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on the incidence of recurrent colorectal adenomas: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1). doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3757-8.

- Pommergaard H-C, Burcharth J, Rosenberg J, Raskov H. Aspirin, calcitriol, and calcium do not prevent adenoma recurrence in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2016;150 (1):114–122.e4. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.09.010.

- Hull MA, Sprange K, Hepburn T, et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid and aspirin, alone and in combination, for the prevention of colorectal adenomas (seAFOod Polyp Prevention trial): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled, 2 × 2 factorial trial. Lancet. 2018;392 (10164):2583–2594. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31775-6.

- Benamouzig R, Uzzan B, Deyra J, et al. Association pour la Prévention par l’Aspirine du Cancer Colorectal Study Group (APACC). Prevention by daily soluble aspirin of colorectal adenoma recurrence: 4-year results of the APACC randomised trial. Gut. 2012;61(2):255–261. 10. 1136/gutjnl-2011-300113

- Friis S, Riis AH, Erichsen R, et al. Low-dose aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and colorectal cancer risk: a population-based, case-control study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(5):347–355. doi:10.7326/M15-0039.

- García Rodríguez LA, Soriano-Gabarró M, Bromley S, et al. New use of low-dose aspirin and risk of colorectal cancer by stage at diagnosis: a nested case–control study in UK general practice. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1). doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3594-9.

- McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods RL, et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379 (16):1519–1528. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1803955.

- McNeil JJ, Nelson MR, Woods RL, et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause mortality in the healthy elderly. N Engl J Med. 2018;379 (16):1519–1528. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1803955.

- Stürmer T, Glynn RJ, Lee IM, Aspirin use and colorectal cancer: post-trial follow-up data from the Physicians’ Health Study. Ann Intern Med.1998;128(9):713–720. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-128-9-199805010-00003.

- Cook NR, Lee I-M, Gaziano JM, Low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cancer: the Women’s Health Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294(1):47–55. doi:10.1001/jama.294.1.47.

- Burn J, Bishop DT, Chapman PD, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled prevention trial of aspirin and/or resistant starch in young people with familial adenomatous polyposis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011;4(5):655–665. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0106.

- Restivo A, Cocco IMF, Casula G, et al. Aspirin as a neoadjuvant agent during preoperative chemoradiation for rectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2015;113(8):1133–1139. doi:10.1038/bjc.2015.336.

- Rothwell PM, Wilson M, Price JF, et al. Mehta Z. Effect of daily aspirin on risk of cancer metastasis: a study of incident cancers during randomised controlled trials. The Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1591–1601. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60209-8.