27th November 2023, A/Prof Chee L Khoo

Although moderate to severe acne is pretty common in primary care, our management tends to be haphazard. We have our favourite topical and oral therapy but I am not sure that that is evidence-based nor pathophysiological in our approach. When all else fails, we refer on to our friendly dermatologist. I recently attended a brilliant lecture at the Melbourne GPCE presented by Dr Ryan de Cruz, a Melbournian dermatologist. I wonder why we were not taught the management principles all these years. Here is my take on the systematic approach to the management of acne in primary care.

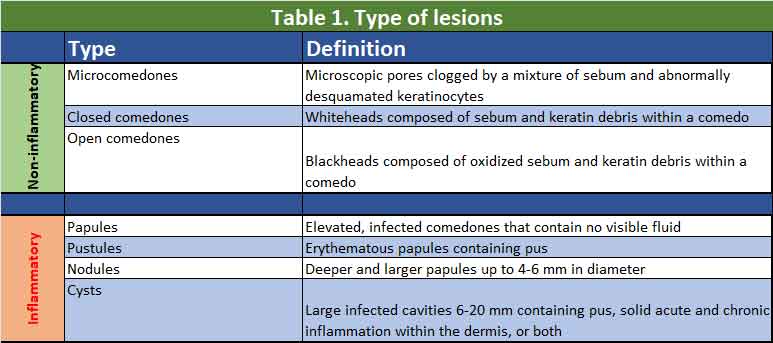

The skin lesions defined

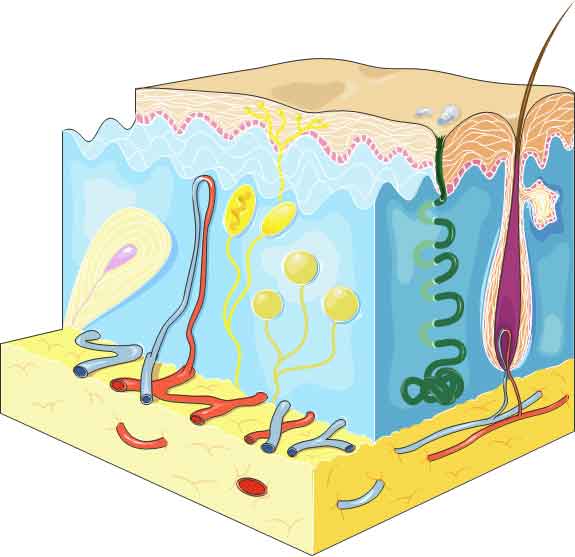

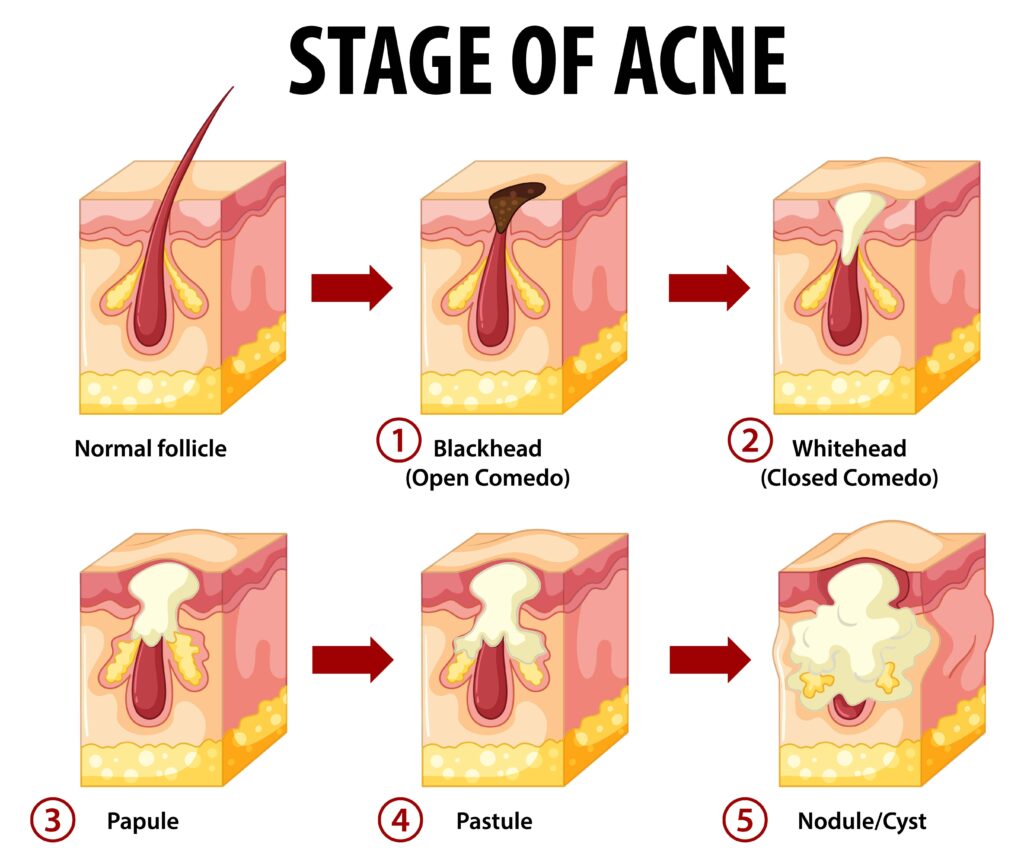

Acne occurs on the affected individuals’ face, neck, chest, upper back, and upper arm areas, where large, hormonally responsive sebaceous glands are abundant. Acne presents as a variety of polymorphic lesions starting with comedones (open or closed) which are generally non-inflammatory which can become inflamed to become papules, pustules and cysts. See Figure 1 and Table 1.

Pathophysiology of acne

There are 4 components in the formation of acne:

- Hormonally determined excess of sebum production by sebaceous gland

Acne develops as a result of hypersensitivity of the sebaceous glands to normal levels of circulating androgens. The level of sensitivity is different for different people. Most patients with acne vulgaris typically have normal androgen levels in their body. However, in certain conditions such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and adrenal or ovarian tumours, excessive androgen production is produced in the body, ultimately leading to acne. This observation supports the significance of androgens in the development of acne. Furthermore, acne does not typically develop before an individual reaches adrenarche, which is the stage when levels of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), an adrenal androgen precursor, are high.

While treatment with the newer oral contraceptive pill which contains an anti-androgen, cyproterone acetate might address the contribution of androgen, the other elements in the pathophysiology is not addressed (see below). A short course of spironolactone is a better option unless contraception is needed anyway.

In addition to the adrenal glands and gonads (men) producing androgens, sebaceous glands can also synthesize androgens through the conversion of DHEAS to testosterone via the action of several enzymes. The sebaceous gland converts testosterone to 5-alpha-dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Sebaceous glands and the outer root sheath keratinocytes of the follicular epithelium have androgen receptors that bind DHT and testosterone. DHT has a greater affinity for these receptors than testosterone. Androgens stimulate sebaceous glands’ growth and secretory function, leading to seborrhoea (excess sebum) and acne formation. Sebum also acts as a growth medium of the bacteria, cutibacterium acnes.

Numerous studies have provided evidence supporting the genetic component of acne. Individuals with affected first-degree family members have a risk of developing acne that can be as high as 3 times greater compared to individuals without a family history of the condition.[1-2].

2. Altered follicular keratinisation leading to comedone formation

Open comedones form when the pilosebaceous orifice becomes plugged with sebum and appears as papules with a central, dilated follicular orifice containing grey, brown, or black keratotic material. Closed comedones form when keratin and sebum block the pilosebaceous orifice beneath the skin surface. They appear as dome-shaped, smooth papules that can be skin-coloured, whitish, or greyish in appearance.

3. Cutibacterium acnes (previously Propionibacterium acnes P. acnes ) colonisation and proliferation in the pilosebaceous unit

C acnes is widely considered a prominent commensal bacterium within the microbiome of the pilosebaceous follicles. The presence of C acnes can trigger both innate and adaptive immune responses, thereby contributing to the inflammatory responses observed in acne.

4. Inflammation and consequent release of inflammatory mediators into the skin

The acne-associated strains of C acnes have been found to possess a heightened capacity to stimulate the pro-inflammatory cascade, specifically involving TH17 cells. These TH17 cells secrete cytokines such as interferon (IFN)-gamma and interleukin (IL)-17, which promote inflammation. In contrast, the strains associated with healthy skin have been shown to stimulate TH17 cells to produce the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10.[3]. The pathogenicity of specific strains of C acnes, along with the variations in the host’s inflammatory responses to the strains colonizing the skin, may contribute to the diversity observed in the prevalence and severity of acne.[4].

Topical therapy

The basic skin care

It is essential to promote the use of gentle skin cleansers instead of harsh soaps or scrubs, as soaps tend to have a higher pH level than the skin. This higher pH can lead to skin irritation and dryness. Aggressive scrubbing and picking of the skin should be discouraged as it may promote the development of new acne lesions and scarring. Selecting non-comedogenic skin products, such as gels and fluids, is essential to avoid blocking the pores.

General skin care creams or gels often contains moisturisers, salicylic acid, azelaic acid and niacinamide. An example of such a cream Efflaclar advertised for oily acne prone skin. Benzyl peroxide containing products such as Benzac 2.5 – 5.0 % can be use as basic treatment for the mildest of acne. They do have a mild anti-keratolytic action. They tend to dry the skin a little and bleech hair and clothing. It is not suitable in pregnancy.

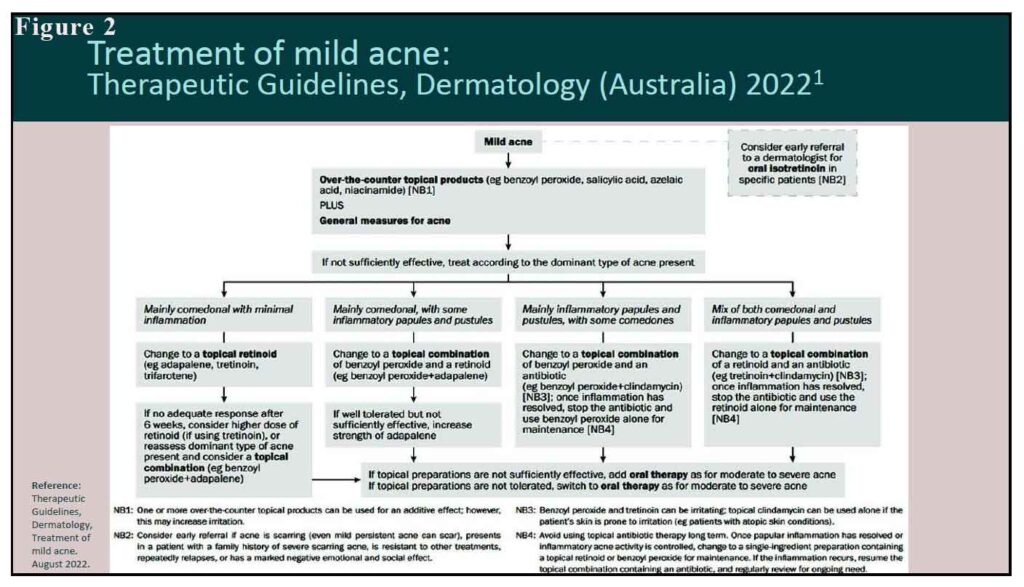

If the acne is more than just little mild and the basic skin care above is not sufficient to control the acne then we need to see which acne component is present:

Limited inflammation but mainly comedones

As mentioned above, comedones are formed when the pilosebaceous orifice becomes plugged with sebum +/- keratin. We need a retinoid either tretinoin or adapalene. We can use Steiva A (containing tretinoin) or Differin (containing adapalene) alone or we can use Epiduo 1% or Epiduo Forte (3%) which contains benzyl peroxide and adapalene. Both benzyl peroxide and adapalene can cause skin irritation and photosensitivity on their own and definitely in combination. One will need to start at low doses. Neither are suitable for pregnant women.

A lot of inflammation (papules) and pustules with some comedones

We need benzyl peroxide in combination with a topical antibiotic (clindamycin) such as Duac. Once the inflammation/infection is settled, use the benzyl peroxide alone for maintenance.

A lot of inflammation, pustules and a lot of comedones

We need a stronger anti-keratolytic in combination with clindamycin such as Acnatac which contains tretinoin with clindamycin. Once the inflammation/infection is settled, use the retinoid (tretinoin or adapalene) alone for maintenance.

Oral therapy

If inflammation/infection is not adequately settle with topical clindamycin, then the addition of a short course of oral doxycycline is recommended. If the oily skin continues to be a problem, an addition of hormonal therapy (spironolactone or cyproterone acetate) may be necessary. Progesterone only contraceptive worsens acne and should be avoided.

If the above measures still don’t control the acne, a referral to a dermatologist is warranted. Consider early referral if acne is scarring (even mild acne can scar), if there is family history of severe scarring acne), severe emotional effect is present or there is repeated relapses.

Acne is a chronic skin condition. Treatment is usually life long although the severity may wax and wanes.

References:

- Di Landro A, Cazzaniga S, Parazzini F, Ingordo V, Cusano F, Atzori L, Cutrì FT, Musumeci ML, Zinetti C, Pezzarossa E, Bettoli V, Caproni M, Lo Scocco G, Bonci A, Bencini P, Naldi L., GISED Acne Study Group. Family history, body mass index, selected dietary factors, menstrual history, and risk of moderate to severe acne in adolescents and young adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012 Dec;67(6):1129-35

- Xu SX, Wang HL, Fan X, Sun LD, Yang S, Wang PG, Xiao FL, Gao M, Cui Y, Ren YQ, Du WH, Quan C, Zhang XJ. The familial risk of acne vulgaris in Chinese Hans – a case-control study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007 May;21(5):602-5

- Agak GW, Kao S, Ouyang K, Qin M, Moon D, Butt A, Kim J. Phenotype and Antimicrobial Activity of Th17 Cells Induced by Propionibacterium acnes Strains Associated with Healthy and Acne Skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2018 Feb;138(2):316-324.

- Sugisaki H, Yamanaka K, Kakeda M, Kitagawa H, Tanaka K, Watanabe K, Gabazza EC, Kurokawa I, Mizutani H. Increased interferon-gamma, interleukin-12p40 and IL-8 production in Propionibacterium acnes-treated peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patient with acne vulgaris: host response but not bacterial species is the determinant factor of the disease. J Dermatol Sci. 2009 Jul;55(1):47-52

- Therapeutic Guidelines, Dermatology, Treatment of mild acne. August 2022.