27th January 2024, NIA Diagnostic Imaging

Intracranial haemorrhage (ICH) is defined as any bleeding within the intracranial vault, which includes the brain parenchyma and the surrounding meningeal spaces. ICH is associated with severe outcomes, including a 30-day mortality rate of 35–52%, with only 20% of survivors expected to fully recover within 6 months. Hence, ICHs are classified as medical emergencies, requiring immediate diagnosis and treatment to ensure the highest possible survival chances. (2, 4)

TYPES OF INTRACRANIAL HAEMORRHAGES

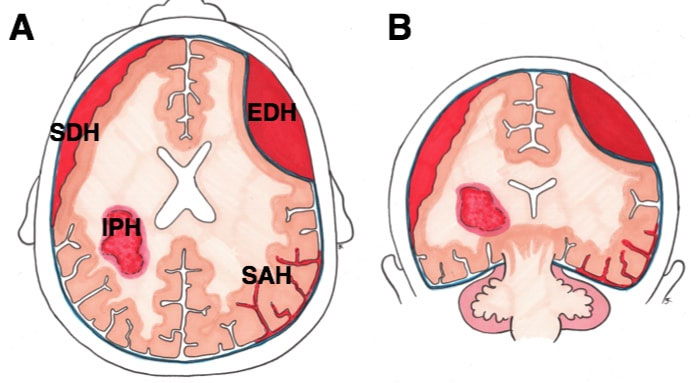

Intracranial haemorrhage can be classified into four types: epidural, subdural, subarachnoid, and intraparenchymal haemorrhage. Each form of haemorrhage differs in terms of origin, findings, prognosis, and outcome:

Epidural haematoma (EDH) refers to bleeding in the space between the dura mater and skull. It is caused by blunt or penetrating head trauma, usually in the temporal region, resulting in the rupture of the meningeal

artery. Patients with an EDH may also present with a temporal bone fracture. (3, 7)

Subdural haematoma (SDH) refers to bleeding between the inner layer of the dura and the arachnoid mater of the meninges. Similar to EDH, SHD is typically caused by traumatic or penetrating head injuries; however,

they can occasionally arise spontaneously. They arise when a bridging vessel between the brain and skull is stretched, damaged, or ripped, generating bleeding into the subdural region. (3, 7)

Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) is defined as bleeding into the subarachnoid space. SAH can be classified as either a non-traumatic or traumatic haemorrhage. Non-traumatic SAH occurs when a cerebral aneurysm ruptures, while traumatic SAH is typically caused by blunt or penetrating trauma as well as sudden acceleration changes to the head. (3, 7)

Intraparenchymal haemorrhage (IPH) is described as bleeding into the brain’s functioning tissue, or parenchyma. IPH can be caused by a variety of conditions, including hypertension, arteriovenous malformation, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis, aneurysm rupture, tumour, head trauma, infection, etc. (3, 7)

EDH = Epidural

IPH = Intraparenchymal

SAH = Subarachnoid

SDH = Subdural

COMPUTERISED TOMOGRAPHY OF INTRACRANIAL HAEMORRHAGE

Non-contrast CT (NCCT) is regarded as the gold standard for diagnosing ICH as it is readily available, fast, has minimal contraindications, and has high sensitivity for bleeding. Aside from providing a diagnosis, CT may

additionally demonstrate the site of a hematoma, its extension into the ventricular system, the presence of surrounding oedema, the development of a mass effect, and a midline shift. Furthermore, NCCT can predict the likelihood of haemorrhage expansion, making it a useful tool in decision-making and prognosis. (5, 7)

Contrast-enhanced scans (especially CT angiography) can also be used to forecast future haemorrhage expansion, as evidenced by the spot sign, which demonstrates blood pooling within a pre-existing haematoma.

(7)

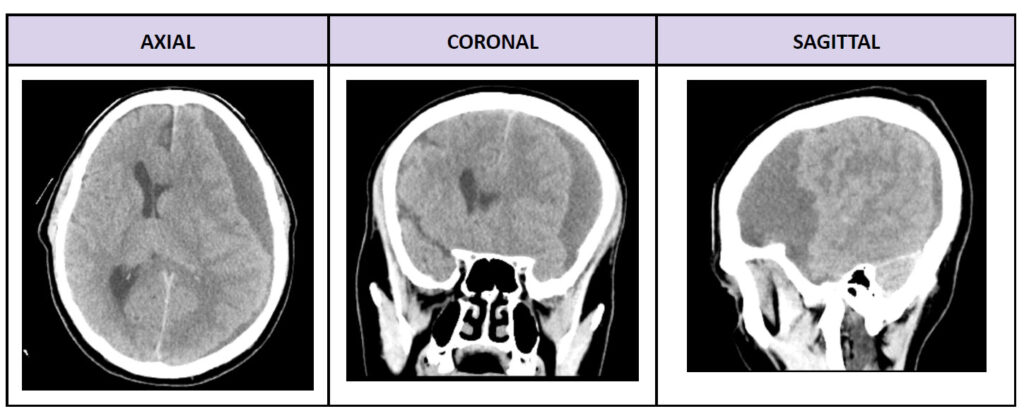

CASE STUDY: NIA DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING – SUBDURAL HAEMATOMA

An ambulant 60-year-old male presented with severe dizziness, confusion, and headaches three weeks after being involved in a motor vehicle accident (MVA). After his initial MVA, the patient attended the hospital

immediately, and medical reports stated that a minute subarachnoid haemorrhage had been detected in his right frontal lobe. After formal evaluation and treatment, the patient was eventually discharged.

The patient was referred to NIA Diagnostic Imaging for a non-contrast CT brain examination, a progress scan of the initial haemorrhage, and to follow-up on his worsening symptoms. A sizable subdural haematoma in the brain’s left frontal, temporal, and occipital areas was visible on the CT

scan, along with a noticeable midline displacement. Following an urgent discussion between the radiologist and the patient’s referring doctor, both doctors agreed to send the patient to the hospital immediately.

AXIAL CORONAL SAGITTAL

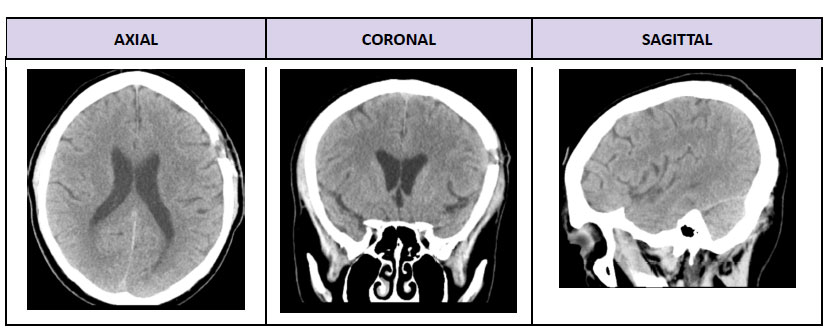

Two weeks later, the patient returned for a non-contrast CT brain scan of the previously diagnosed left SDH. The images demonstrated a left frontal burr hole with mild subdural thickening at the surgical site. There were

no subdural haematomas, haemorrhages, masses, or midline shifts.

When presented with urgent situations, NIA Diagnostic Imaging strives to prioritise the health and wellbeing of all patients, and to ensure they receive prompt diagnosis and treatment. It is through efficient interprofessional collaboration between our radiology team and the patients’ managing clinicians that we are able to escalate situations such as the aforementioned.

REFERENCES

- Abbasi, B., Ganjali, R., Akhavan, R., Tavassoli, A., & Khojasteh, F. (2023). The accuracy of non-contrast brain CT scan in predicting the presence of a vascular etiology in patients with primary intracranial

hemorrhage. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 9447. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-36042-2 - Alshumrani, G., Al abo nasser, B., Alzawani, A., Alsabaani, A., Shehata, S., & Alhazzani, A. (2021). The role of computed tomography angiogram in intracranial hemorrhage. Do the benefits justify the

known risks in everyday practice? Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery, 200, 106379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2020.106379 - Bucker, A., Westerlaan, H., Mazuri, A., Uyttenboogaart, M., & Smithuis, R. (n.d.). The Radiology Assistant : Traumatic Intracranial Hemorrhage. Radiologyassistant.nl. Retrieved January 8, 2024, from

https://radiologyassistant.nl/neuroradiology/hemorrhage/traumatic-intracranial-haemorrhage - Caceres, J. A., & Goldstein, J. N. (2012). Intracranial Hemorrhage. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America, 30(3), 771–794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2012.06.003

- Hillal, A., Ullberg, T., Ramgren, B., & Wassélius, J. (2022). Computed tomography in acute intracerebral hemorrhage: neuroimaging predictors of hematoma expansion and outcome. Insights into Imaging, 3, 180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13244-022-01309-1

- Jones, J. (2023, November 25). Intracerebral hemorrhage | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org. Radiopaedia. https://radiopaedia.org/articles/intracerebral-haemorrhage

- Morotti, A., & Goldstein, J. N. (2016). Diagnosis and Management of Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America, 34(4), 883–899. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emc.2016.06.010

- Rowe, A. (2021). Diagram demonstrating types of intracranial bleeds, across (A) axial and (B) coronal views. In TeachMe Surgery.

https://teachmesurgery.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Intracranial-Bleeds-1.jpg - Tenny, S., & Thorell, W. (2023, February 13). Intracranial Hemorrhage. PubMed; StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470242/#:~:text=Intracranial%20hemorrhage%20encompasses%20four%20broad

- Wu, E., Marthi, S., & Asaad, W. F. (2020). Predictors of Mortality in Traumatic Intracranial Hemorrhage: A National Trauma Data Bank Study. Frontiers in Neurology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.587587