22nd May 2021, Dr Chee L Khoo

Clinical inertia in heart failure (HF) treatment means deferred initiation of additional proven beneficial therapy, which ultimately leads to preventable adverse HF events. Hospitalisation for worsening HF is a prognostically significant event in the clinical course of a patient with chronic HF (1,2). Hospitalisation for HF (hHF) identifies patients who are at high risk for subsequent disease progression, requirement for advanced therapies, and cardiovascular death. Because of their elevated risk profile, patients who have been hospitalised for HF represent an important target population for reducing overall HF morbidity and mortality (3). But how quickly does treatment for heart failure work in reducing the harm?

We explored quadruple therapy in heart failure a few weeks ago as the gold standard in treatment of heart failure. We also discussed the treatment inertia when managing this condition which has high mortality rate. Often these patients are instructed to see their GP upon discharge from hospital and it is another 6-8 weeks before they get to see their cardiologist. Should we wait till the patient sees the cardiologist or should we escalate treatment in patients with heart failure.

The cardiovascular outcome trials (CVOTs) EMPA REQ (4), CANVAS (5) and DECLARE TIMI 58 (6) all consistently show that SGLT2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), empagliflozin, canagliflozin and dapagliflozin reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). In their secondary outcomes, the CVOTs were also shown to reduce hHF. CREDENCE (7), DAPA-HF (8) and EMPEROR-REDUCED were dedicated heart failure trials which recruited only patients who had heart failure. They showed that SGLT2 inhibitors reduced hHF in patients irrespective of whether the patients have diabetes or not.

DAPA-HF was a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) that evaluated the efficacy and safety of dapagliflozin, 10 mg daily, compared with a matching placebo over 18 months. Participants with HF needed to be in NYHA Class II or greater, ejection fraction of < 40% and elevated NT-proBNP. Patients were excluded from participation in the trial if they were currently hospitalised for acute decompensated HF or had been hospitalised for HF within 4 weeks of randomisation. The primary efficacy outcome in the trial was the composite of an episode of worsening HF – an unplanned hospital admission or urgent HF visit resulting in intravenous therapy for HF.

A sub-analysis of the DAPA-HF trial was recently published. The report yielded some very interesting and important results that are pertinent to management of our patients in primary care. To explore the timing of onset of the clinical benefit of dapagliflozin vs placebo, they compared the hazard ratios (HRs) of the primary outcome occurring in the dapagliflozin with similar HR in the placebo groups at various time points. They explored the association of those HRs with timing of the most recent hospitalisation for heart failure. About 50% of participants were never hospitalised for HF before, ~25% were hospitalised within the last 12 months while another ~25% were hospitalised >12 months ago.

Results

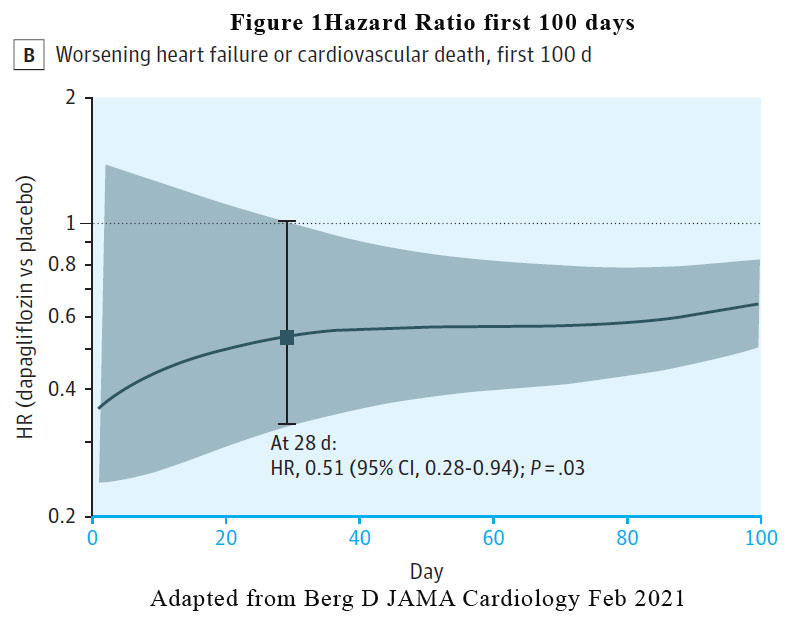

Timing of benefit

A reduction in the risk of the primary efficacy outcome of worsening HF event or cardiovascular death was rapidly apparent. The benefit of dapagliflozin vs placebo reached statistical significance by 28 days post randomisation (HR at 28 days, 0.51 [95% CI, 0.28-0.94, p = .03). See Figure 1. The pattern of benefit was similarly observed when the individual components of the composite outcome was examined (worsening heart failure HR at 28 days: 0.48, cardiovascular death HR at 28 days: 0.87) and the benefit persisted at the end of the study of 18 months.

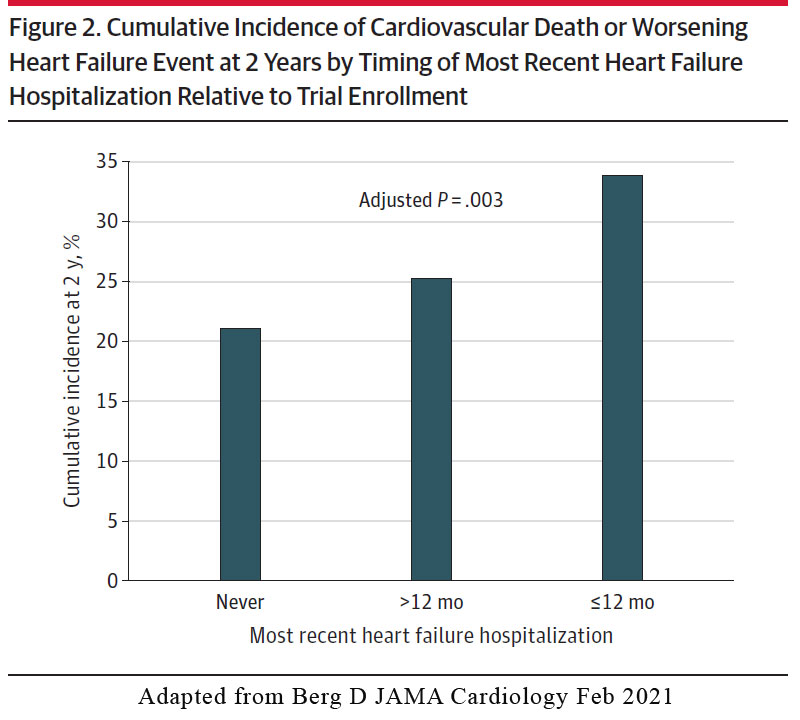

Association with last heart failure hospitalisation

In the placebo arm, there was a stepwise increase in risk for the primary efficacy outcome of cardiovascular death or worsening HF event according to timing of the most recent HF hospitalisation, ranging from a 2-year Kaplan-Meier event rate of 21.1% in patients with no prior history of HF hospitalization, 25.3% in those with an HF hospitalization > 12 months prior to enrolment, and 33.8% in those with an HF hospitalisation < 12months of trial enrolment (Figure 2).

Efficacy of dapagliflozin

Dapagliflozin reduced the relative risk of the primary outcome. In participants who were never hospitalised for heart failure the reduction was 16%, in those who were hospitalised >12 months, the reduction was 27% while in those with an HF hospitalisation <12 months of trial enrolment, the reduction was 36%. The pattern of reduction was similar irrespective of whether the participants had diabetes or not.

Implications for primary care

Despite an extensive evidence base from clinical trials and clear guidelines from cardiovascular professional societies, use of comprehensive medical therapies for the treatment of HFrEF remains woefully suboptimal in clinical practice, and most patients are treated only with renin-angiotensin

system inhibitors and β-blockers (2). The rapid time (28 days) to clinical benefit highlights the risk of delaying initiation of dapagliflozin in patients with HF. This is particularly pertinent in those who has just been discharged from hospital following admission for heart failure. We cannot and should not wait till their next appointment with the cardiologist.

Unfortunately, SGLT2 inhibitors is only approved under the PBS for patients with type 2 diabetes. They have been approved in the UK and USA for treatment of heart failure for patients without T2D. A similar approval is anticipated very soon. In the meantime, if you have a patient who could benefit from dapagliflozin treatment for their heart failure but not have T2D, AstraZeneca has a Product Familiarisation Program (PFP) which will provide dapagliflozin to your patients for free while it is not on the PBS. Give your local AZ rep a call.

References:

- Solomon SD, Dobson J, Pocock S, et al; Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM) Investigators. Influence of nonfatal hospitalization for heart failure on subsequent mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116(13):1482-1487. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.696906

- Bello NA, Claggett B, Desai AS, et al. Influence of previous heart failure hospitalization on cardiovascular events in patients with reduced and preserved ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 2014;7(4): 590-595. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.001281

- Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA focused update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 2017;136(6):e137-e161. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000509

- Zinman B, Lachin JM, Inzucchi SE. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and Mortality in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016 Mar 17;374(11):1094. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1600827. PMID: 26981940.

- Neal B, Perkovic V, Matthews DR. Canagliflozin and Cardiovascular and Renal Events in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017 Nov 23;377(21):2099. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1712572. PMID: 29166232.

- Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, Mosenzon O, Kato ET, Cahn A, Silverman MG, Zelniker TA, Kuder JF, Murphy SA, Bhatt DL, Leiter LA, McGuire DK, Wilding JPH, Ruff CT, Gause-Nilsson IAM, Fredriksson M, Johansson PA, Langkilde AM, Sabatine MS; DECLARE–TIMI 58 Investigators. Dapagliflozin and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jan 24;380(4):347-357. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1812389. Epub 2018 Nov 10. PMID: 30415602.

- Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, Bompoint S, Heerspink HJL, Charytan DM, Edwards R, Agarwal R, Bakris G, Bull S, Cannon CP, Capuano G, Chu PL, de Zeeuw D, Greene T, Levin A, Pollock C, Wheeler DC, Yavin Y, Zhang H, Zinman B, Meininger G, Brenner BM, Mahaffey KW; CREDENCE Trial Investigators. Canagliflozin and Renal Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes and Nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jun 13;380(24):2295-2306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1811744. Epub 2019 Apr 14. PMID: 30990260.

- McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, et al; DAPA-HF Trial Committees and Investigators. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381

- Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Pocock SJ, Carson P, Januzzi J, Verma S, Tsutsui H, Brueckmann M, Jamal W, Kimura K, Schnee J, Zeller C, Cotton D, Bocchi E, Böhm M, Choi DJ, Chopra V, Chuquiure E, Giannetti N, Janssens S, Zhang J, Gonzalez Juanatey JR, Kaul S, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Merkely B, Nicholls SJ, Perrone S, Pina I, Ponikowski P, Sattar N, Senni M, Seronde MF, Spinar J, Squire I, Taddei S, Wanner C, Zannad F; EMPEROR-Reduced Trial Investigators. Cardiovascular and Renal Outcomes with Empagliflozin in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2020 Oct 8;383(15):1413-1424. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022190. Epub 2020 Aug 28. PMID: 32865377.

- Berg DD, Jhund PS, Docherty KF, Murphy SA, Verma S, Inzucchi SE, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, Langkilde AM, Martinez FA, Bengtsson O, Ponikowski P, Sjöstrand M, Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Sabatine MS. Time to Clinical Benefit of Dapagliflozin and Significance of Prior Heart Failure Hospitalization in Patients With Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. JAMA Cardiol. 2021 May 1;6(5):499-507. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.7585. PMID: 33595593; PMCID: PMC7890451.